William Kennedy

Very Old Bones

This book is dedicated to the Hard Core (they know who they are), and to certain revered and not-so-revered ancestors of the author (they don’t know who they are, for they are dead; but they’d know if they ever got their hands on this book).

Any one who has common sense will remember that the bewilderments of the eyes are of two kinds, and arise from two causes, either from coming out of the light or from going into the light. . and he who remembers this when he sees any one whose vision is perplexed and weak, will not be too ready to laugh; he will first ask whether that soul of man has come out of the brighter life, and is unable to see because unaccustomed to the dark, or having turned from darkness to the day is dazzled by excess of light.

— Plato, The Republic

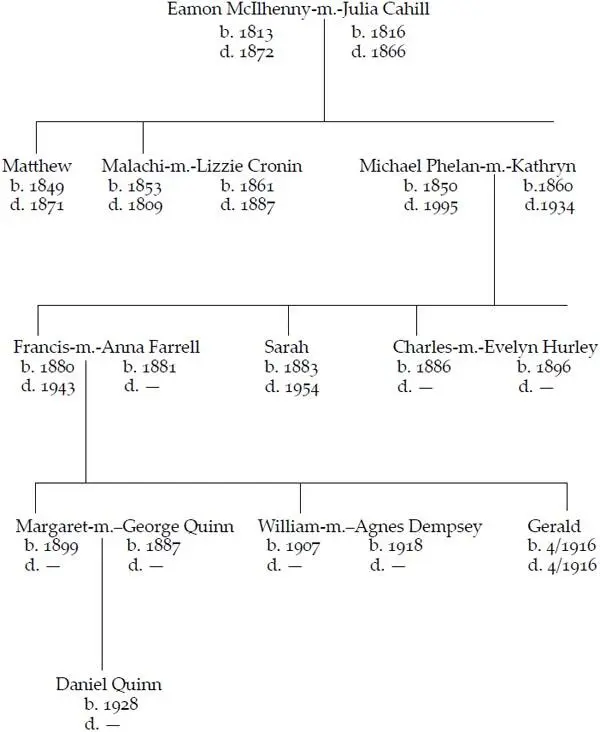

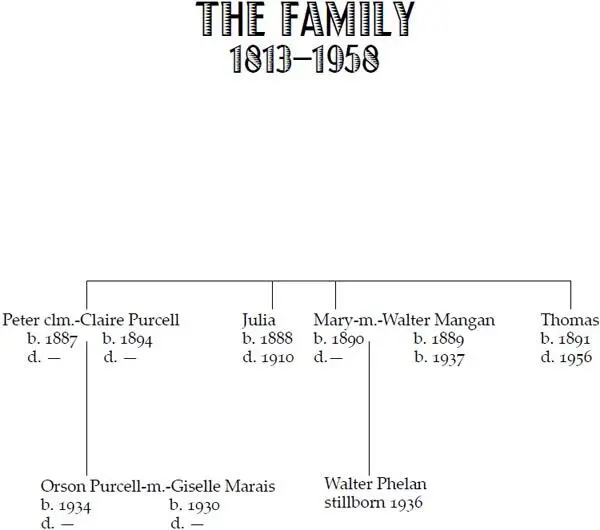

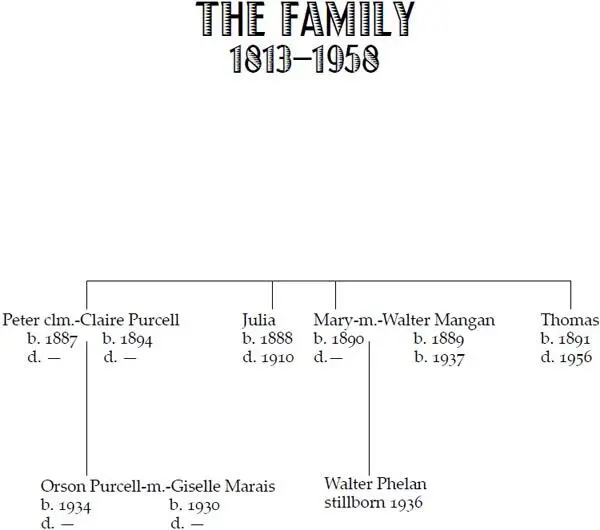

It is Saturday, July twenty-sixth, 1958, the sun will rise in about twenty-five minutes, the air is still, and even the birds are not yet awake on Colonie Street. There is no traffic on North Pearl Street, half a block to the east, except for the occasional auto, police prowl car, or the Second Avenue bus marking its hourly trail. A moment ago fire sirens sounded on upper Arbor Hill, to the west, their wail carrying down on the silent air, interrupting the dreams of the two sleeping occupants of this house, Peter Phelan, a seventy-one-year-old artist, and his putative son, Orson Purcell, a thirty-four-year-old bastard.

“Orson,” Peter called out, “where are those sirens?”

“Not around here,” I said.

“Good.”

He knew as well as I that the sirens weren’t close. His hearing was excellent. But he was reassuring himself that in case of fire Orson was standing by; for I was now the organizer of his life (not his art; he was in full command of that), the putative son having become father to the putative father. His health was precarious, a serious heart condition that might take him out at any instant; and so he abdicated all responsibility for survival and gave himself utterly to his work. I could now hear him moving, sitting up on the side of the bed in his boxer shorts, reaching for the light and for his cane, shoving his feet into his slippers, readying himself to enter his studio and, by the first light of new morning, address his work-in-progress, a large painting he called The Burial.

I knew my sleep was at an end on this day, and as I brought myself into consciousness I recapitulated what I could remember of my vanishing dream: Peter in a gymnasium where a team of doctors had just operated on him and were off to the right conferring about the results, while the patient lay on the operating table, only half there. The operation had consisted of sawing parts off Peter, the several cuts made at the hip line (his arthritic hips were his enemy), as steaks are cut off a loin. These steaks lay in a pile at the end of Peter’s table. He was in some pain and chattering to me in an unintelligible language. I reattached the most recent cut of steak to his lower extremity, and it fit perfectly in its former location. But when I let go of it it fell back atop its fellows. Peter did not seem to notice either my effort or its failure.

“Are you going to have coffee, Orson?” he called out from his room. In other words, are you going to make my breakfast?

“I am,” I said. “Couple of minutes.” And I snapped on the light and sat up from the bed, naked, sweating in the grotesque heat of the morning. I put on a light robe and slippers and went down the front stairs and retrieved the morning Times-Union from the front porch. Eisenhower sending marines into Lebanon for mid-east crisis. Thunderstorms expected today. Rockefeller front runner for Republican nomination for Governor.

I put the paper on the dining-room table, filled the percolator, put out coffee cups and bread plates, and began plotting the day ahead, a day of significance to the family that had occupied this house since the last century. We would be gathering, the surviving Phelans and I, at the request of Peter, who was obeying a patriarchal whim that he hoped would redirect everybody’s life. My principal unfinished task, apart from ridding the house of clutter, was to inveigle my cousin Billy to attend the gathering here, a place he loathed.

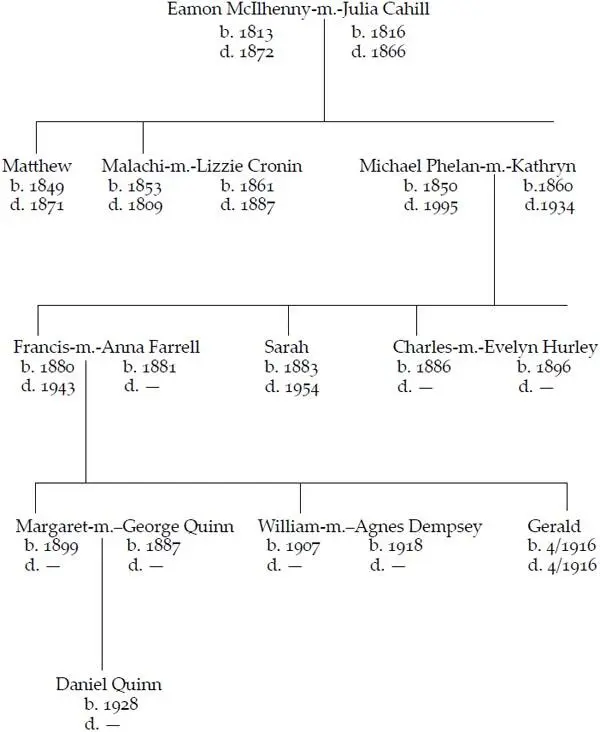

I first came here in 1934 for a funeral. Peter passed me off as the son of his landlady, Claire Purcell (which I was and am), whom he had never brought to this house even for tea, though he had been living with her then in Greenwich Village for more than fifteen years. I liked Albany, liked the relatives, especially my Aunt Molly, who became my nurse after I went crazy for the second time, and I liked Billy, who always tried to tell the truth about himself, a dangerous but admirable trait. I went to college in Albany before and after the war and came here for dinner now and again, slowly getting to know this ancestral place and its inhabitants: the Phelans and the McIlhennys, their loves, their work, their disasters.

I came to see how disaster does not always enter the house with thunder, high winds, and a splitting of the earth. Sometimes it burrows under the foundation and, like a field mouse on tiptoe, and at its own deliberate speed, gnaws away the entire substructure. One needs time to see this happening, of course, and eventually I had plenty of that.

Colonie Street in Arbor Hill was the neighborhood where these people had implanted their lives in the last century. The first Phelans arrived from Ireland in the 1820s to finish digging the Erie Canal and by mid-century were laborers, lumbermen, railroad men, and homemakers of modestly expanding means. The McIlhennys came in the late 1870s, poor as turkeys and twice as wild.

Michael Phelan inherited twenty-one thousand dollars upon the death of his father, a junior partner in a lumber mill, and in 1879 Michael built this house for his bride, Kathryn McIlhenny, creating what then seemed a landmark mansion (it was hardly that) on a nearly empty block: two parlors, a dining room, and seven bedrooms, those bedrooms an anticipatory act of notable faith and irony, for, after several years of marriage, Kathryn began behaving like an all-but-frigid woman. In spite of this, the pair filled the bedrooms with four sons and three daughters, the seven coming to represent, in my mind, Michael Phelan’s warm-blooded perseverance in the embrace of ice.

The siblings were Peter and Molly; the long-absent Francis; the elder sister, Sarah; the dead sister, Julia; the failed priest, Chick; and the holy moron, Tommy. Peter had fled the house in the spring of 1913, vowing never to live here again. But the family insinuated itself back into his life after a death in the family, and he came home to care for the remnant kin, Molly and Tommy.

Peter’s pencil sketches of his parents and siblings (but none of his putative son) populated the walls of the downstairs rooms in places Peter thought appropriate: Francis in his baseball uniform when he played for Washington, hanging beside the china closet, the scene of a major crisis in his life; Julia in her bathing costume, standing in the ankle-deep ocean at Atlantic City, where her mother took her to spend two months of the summer of 1909, hoping to hasten her recovery from rheumatic fever with sea air, this sketch hanging over the player piano; Sarah, without pince-nez, in high-necked white blouse, looking not pretty, for that wasn’t possible for the willfully plain Sarah, but with an appealing benevolence that Peter saw in her, this sketch hanging on the east wall of the front parlor, close to the bric-a-brac Sarah had accumulated through the years, the only non-practical gifts the family ever gave her; for her horizon of pleasure in anything but the pragmatic was extremely limited. Molly hung in the back parlor also, with one foot on the running board of her new 1937 Dodge, looking very avant-garde for that year.

Читать дальше