Bohumil Hrabal - Rambling On - An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bohumil Hrabal - Rambling On - An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, Издательство: Karolinum Press, Charles University, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Rambling On: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab

- Автор:

- Издательство:Karolinum Press, Charles University

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Rambling On: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Rambling On: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Rambling On

Rambling On: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Rambling On: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

~ ~ ~

~ ~ ~

~ ~ ~

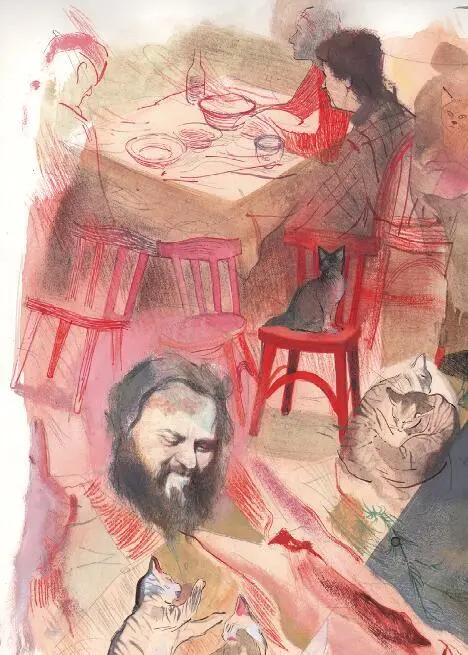

13 LUCY AND POLLY

RATHER LIKE ME, mine host Mr Novák was an odd individual. There were days when he would be welcoming to his patrons, smiling, shaking everyone’s hands, his patrons would bring little somethings for his wife: flowers, a basketful of orange birch boletes, in winter white puddings and celebration soup after they’d slaughtered a pig, then a chunk of smoked pork, and all because he served a fine pint, and when he was in a good mood, he’d ask someone to bring a hare or deer and then put on a feast… all in all, on a good day, he was second to none as publicans go, when his missus was making dumplings, the kitchen windows had to be shut so the dumplings didn’t catch cold, when they brought him his week’s supply of meat direct from the abbatoir, he would lay each piece out on the vast kitchen table and inspect them all with great satisfaction, feasting his eyes on the meat and already speculating what each piece might go on, and when he was in an exceptionally good mood, he would immediately cut slices from a leg of pork and then he’d be round shortly with escalopes quick-fried in butter and drizzled with lemon juice. And when he was having one of his wonderful days, which were getting increasingly rarer, he’d bring round potato fritters, and his speciality was bull’s testicles egg-and-breadcrumbed like Wiener schnitzels and served with tartar sauce. During such times he would sit around with the customers, putting an arm round their shoulders and looking straight at them and taking bookings, and in the evenings his beautiful wife would get her apron and also come and sit with the customers, and we were all happy that at last we had a decent licensee. They had two children, a boy, Vráťa, aged five, who liked to sit on the customers’ laps and nuzzle up to them like a stray kitten, then he also had a tubby ten-year-old daughter, Mílka, who, despite her vast proportions, had the single ambition of becoming a dancer, and so whether in the garden or inside the pub she was always dancing, with a veil or without, and as you approached the Keeper’s Lodge pub-restaurant down the drive, you could see from a distance the two children, the tubby dancer, dancing just for her own pleasure, completely immersed in an ungainly gymnastics, a ballet of gawkiness. The first year, as Christmas was approaching, well, it was absolutely wonderful in our restaurant, ab-so-lute-ly! Franta Vorel brought a spruce for the kitchen, then he cut down a pine for the saloon, in the run-up to Christmas Eve the whole pub helped decorate the tree and meanwhile Mr Novák came round with the brandy and kirsch and that fabulous beer of his, his missus brought in the Christmas cookies, and nearly all the patrons reciprocated with a box of their own cookies from home, and so no one was in any mood to leave before closing time, or even then, and Mr Novák said that they were all his guests, so he locked up and then those wonderful days carried on behind locked doors. Following Christmas Eve, there was Christmas Day and Boxing Day, the guests had their set places, around and among the beer glasses Vráťa laid out his toy railway and the train ran clickety-clack over the tables that had been pushed together, the Christmas tree was a blaze of light and the children sat on everybody’s lap, turn and turn about, snuggling up under the patrons’ chins, and we were all in heaven, because it had been a long, long time since we’d had a publican like Mr Novák. But my reason for liking him was that he loved the cats Lucy and Polly, the two tabbies followed him everywhere, they did everything with him, when he went to the shops through the forest, Lucy and Polly went with him, when the pub closed at two and Mr Novák went mushrooming after lunch, the cats went with him, when he went into the cellar to broach a cask, Lucy and Polly also went with him, when he went to bed, the cats slept with him, and as he sliced and chopped vegetables and meat and got on with the cooking in the kitchen, the cats would sit on the window sill and watch Mr Novák lovingly, and Mr Novák knew, and every now and again, knife in hand and wearing his white apron, he went over to the window, bent to the cats’ level and exchanged head-butts with them, like clinking liqueur glasses when he toasted his customers in the evening. And the cats, Lucy and Polly, like Mr Novák’s children, began wandering among the customers and, just like Vráťa a Míla, they liked to sit on a customer’s lap, curled round on their knees and beneath their protective hand, until such time as the customer rose, and the cats, having wearied of being stroked by humans, would curl up in winter behind the enamel stove and sleep a sweet sleep, and sigh and stretch and expose their brindled gingery tummies, and it was if the entire pub was their mother, they would pat the air with their front paws, trample the air from which they would suck sweet, non-existent milk in the form of cigarette smoke and the chatter that rose and fell into the silence of the inn, silence betokening the flight of an angel passing through, sometimes what rose was shouting and swearing and cursing, other times confused blather and singing, but Lucy and Polly knew that none of it was meant against them, but that it was all part of the music of the inn that was their home. So Lucy and Polly would amble past the chairlegs, miaow, and a customer would open the door for them and they would go outside into the wonderful air of the forest, they would sit on the low wall round the terrace or hop up on one of the red chairs and gaze into the sun or the rain so that anyone coming to the inn… so they could welcome them by rubbing against their trouser leg, or just by giving them a look-over, fondly weighing the new arrival up, and almost every one would stroke them, or say something to them, Lucy and Polly became the livestock of the Keeper’s Lodge, and by turns they would come inside as the fancy took them, or go back out for a run or a rumble in the oakwood. But Mr Novák also had days when every plus became a minus, suddenly his ears would be pinned back like those of a horse about to snap, he wouldn’t bring the beer to the tables, and if he did, then with some snide comment, he wouldn’t serve food, but if he did it was cold, on days like that he wouldn’t sit among his patrons, but lean against the bar counter and stare at them grimly, then suddenly he’d start addressing people by their surnames, though he was on first-name terms with all of them, and one time when he was going through such a phase, we’d gathered on the concrete road in front of the restaurant and there on the inside was a sign: Closed. Cleaning in progress , though only the day before, when Mr Novák had been in a good mood, it had been all first names as he sat among us, and now he’d shut up shop and his face glowed and grinned horribly over the sign, smirking grotesquely like a white mask with Brylcreemed hair, only to vanish behind the drape. As we stood outside the inn, more customers kept arriving, and so we swore and shouted and called out and cursed, why hadn’t he told us the day before… Or there was another time when we’d turned up, pleased to see one another arriving down all the various rides and tracks, sure of being greeted by a fired-up stove because the inn was all lit up like a lighthouse, like a chandelier, but as each of us tried the door-handle, one after another, we discovered it was closed, and when we tapped on the door, no one heard us, we looked in through the taproom window, the one used to pass beers out into the garden on summer days, and we saw that the tables had been pushed together, with white cloths on them, and Mr Novák, in another world, was laying out spoons and forks round the plates, and the plates were linked together with sprigs of asparagus fern, and when we called out: “Come on, Láďa, let us in, we’ll stick by the stove, quiet as mice,” we called him by his first name because the night before he’d called us by ours, Mr Novák, lost in his other world and as if under a spell, took a step back and looked, from the door and in sheer delight, at all these preparations for the wedding on the coming day, which had been booked by some outsider from far away, the stove grinned with its red-hot coals, and outside it was cold. And Mr Novák condescended to respond and spoke into the drizzle in an alien voice: “Can I help you? Only the outside’s open today, can’t you see?” he said, exasperated, so we stood outside in the drizzling rain, or sat out in it on garden seats and abandoned chairs, drinking beer, we could never get over the swings in the psychological weather of our publican’s mood, he, with great flair, went on setting out wine glass after wine glass, shot glass after shot glass, to go with the wines and liqueurs and aperitifs in the order they would be drunk from the next day… and we put up our empty glasses, gesticulating, shouting, but Mr Novák, miles away, kept stepping back to savour from every angle the table so lavishly spread for the morrow’s wedding feast. And when he did deign to notice us, he pulled our pints with evident distaste and resentment and revulsion, and when none other than Mr Hubka, the engineer, begged him to let him have another one to hold in reserve, Mr Novák came to the serving window, released the catch and slammed it down so hard that Mr Hubka barely got his hands away in time, otherwise he’d have lost his fingers. But I too was shaking with rage, I too, like the other sad and disappointed customers, swore that I’d never come back to this inn, that I was here for the last time, I too was thinking of all the things I’d do to Mr Novák, but as I looked inside the brightly lit restaurant, I had to concede, as anyone else would, that when Mr Novák was in a good mood, he was the most likeable man and publican in the world, that our Mr Novák had arranged the tables for the wedding breakfast with tremendous good taste, and when I saw Lucy and Polly sitting on a chair and turning their little heads in whatever direction Mr Novák went next, and every now and again Mr Novák couldn’t stop himself — if perhaps to show us that the cats meant more to him than we, his outdoor customers, did — from bending down to let Lucy and Polly take turns at kissing his forehead, and then he was back to fetching bunches of flowers or pots of cyclamen, or twisting ever more festoons of asparagus fern for the even fancier cloth that went over all the tables together. And when Mr Novák had satisfied himself for the last time, he bent down and picked Lucy and Polly up, and they seemed to have been waiting for just that, they floated up into his embrace, then with the beloved cats on one arm and his other hand on the light switch, all the customers abandoned any sense of dignity, we on the outside held our glasses up in the drizzling rain, pointing and tapping on the window for him to have pity, for Mr Novák to be so kind as to recall those glorious days past, those times when a pig was slaughtered, those walks together on days off as far as Elegant Antonia and the giant spruce, but Mr Novák, having feasted his eyes on the proffered empty glasses and imploring faces, switched the light off. We’d put every last scrap of earnest, canine devotion into our eyes, every ounce of humility and entreaty, but Mr Novák had spurned us, just as on any of those other days when he went bonkers, when he was overcome with self-pity and sadness and grouchiness, when his patrons became so obnoxious to him that not only did he not want to see them, but he actually wanted to humiliate them, and to that end he would always choose a day when no one would, or could, have expected it even in their wildest dreams. Yet I was fond of Mr Novák, because my own nature was not dissimilar, also apt to vacillate between polar opposites, one day I’d embrace the whole of mankind, another I’d be thinking up the most ghastly genocide for the lot. But I also liked Mr Novák because of his love for Lucy and Polly, and now that he’d put out the lights and left us outside in the drizzling rain and was savouring the notion of us contemplating the most horrible way of doing away with him, having first tortured him in ways as yet undreamed-of by any Korean executioner, I knew that Mr Novák was in his little room, lying on his back, listening out, with Lucy and Polly lying on his chest and he’d be stroking them and showing them his love. Like me, Mr Novák was an odd character. So it came to pass that those dark days grew in number, and all the more did we appreciate it when Mr Novák lit up and smiled at us, by which moment we would forget to a man all the things he had done to us, because we were glad to be able to meet up at the inn, given that from six o’clock onwards the sole preoccupation of any true man of Kersko and its forests is to spend a pleasant evening over a pint in the pub, and all the banter and chit-chat, the arguments and imbecilities are a brilliant way to unwind from our daily tribulations, so our serenity is fully restored and as we cycle home at night we’re on a par with a newborn child, though that only on the assumption that mine host has been good to us. Then the day came when Mr Novák said what we’d long known, that he was moving in two days’ time, he wished to invite us to his last day at the inn, he would put on a feast and we would part friends. And it came to pass that that evening, after we’d tempered our food intake at home and were looking forward to the last supper, when we entered the pub one by one, Mr Novák was his alien self, there was no fire in the stove, the chairs were up-ended on the tables by the window, and Mr Novák and his good lady were packing their belongings into boxes, Mr Novák served his last beer, already a bit flat, beer with no head on it, like the specimen you take in a beer bottle to Mikolášek, the miracle doctor, for him to guess not only what’s wrong with you, but also what infusion will put it right. And again there was that sorry sight of everyone sitting in their coats, perplexed and disappointed and feeling cheated, and they stared towards the door to see each new arrival’s face burning bright with joy and anticipation, then as each one entered, how they were taken aback, then stunned and lamed, but always with that glowing physiognomy that couldn’t be dimmed. In the end everyone sat down and Mr Novák brought us our headless beers without a word… and when Mr Franc said out loud that the beer had no head on it, the rest turned towards him in horror at his presumption… and Mr Novák went into the kitchen, brought a whisk, the kind you use to whisk flour into a sauce to thicken it, whisked the beer into a froth and set the whisk down on an ashtray, the bubbles of froth popped quietly and silence descended, and we were all so debilitated by the ignominy that no one felt able to rise and leave, because the greatest dishonour and insult to a true beer-drinker is lacklustre, flat beer… And Lucy and Polly had no idea, any more than us, what they were in for, they padded around among the boxes and crates and helped pack the kitchen utensils that were Mr Novák’s own, his butchery knives, a full set of them, with which, on his good days, he would lovingly carve meats and draw up the menu, which on any of those happy days had at least six dishes to chose from, whereas on lean days Mr Novák had no salami, nor would he offer so much as bread and dripping. And it came to pass that Mr Novák stood legs astride and arms akimbo and was about to tell us something terrible, something that he had always held against us and that he would take with him to any other pub in future, since it wasn’t loathing for us and our names, but a grudge against all patrons as such. He raised one finger and we goggled, some rose in terror, but all eyes converged on Mr Novák’s finger, like bicycle spokes on the hub, but he curled it back into his palm and gave a wave of his hand as if it were pointless to say anything by way of a farewell, with that hand he was damning us just as when Christ, in paintings of the Last Judgement, damns those who have lapsed from faith, those who he is consigning to eternal damnation… And Vráťa opened the door and came running in, artless and childlike, nestling up to us and pointing to the half-open door in which a dancing Mílka, the daughter, appeared, now bespectacled and obese, but dancing with a veil, raising only her arms, because she couldn’t lift herself off the ground, hop, yet she danced with so much feeling in her eyes, with such absorption, that she only added to the general confusion and tension, she danced between the tables as if to bid a farewell of which she as yet knew nothing, because the moment she got in from school, she just danced and kept dancing, right through the weekend and on all school-free days, and so she danced us her dance — more an ungainly, if emotive shuffle, with eyes ablaze and cheeks flushed — for the last time, then she danced off out into the darkness, and little Vráťa banged the door behind her so hard that all the glass panes fell out. The tinkling glass helped us pull ourselves together, and one by one we left the farewell feast to take the shortest way home, humiliated, wretched, hungry, to wipe up whatever relics of dinner with a piece of bread or make do with some bread and dripping, since, in anticipation of our last supper at the pub, we’d declined the roast at home.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Rambling On: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Rambling On: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Rambling On: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.