Bohumil Hrabal - Rambling On - An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bohumil Hrabal - Rambling On - An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, Издательство: Karolinum Press, Charles University, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Rambling On: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab

- Автор:

- Издательство:Karolinum Press, Charles University

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Rambling On: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Rambling On: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Rambling On

Rambling On: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Rambling On: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

~ ~ ~

~ ~ ~

~ ~ ~

10 FINING SALAMI

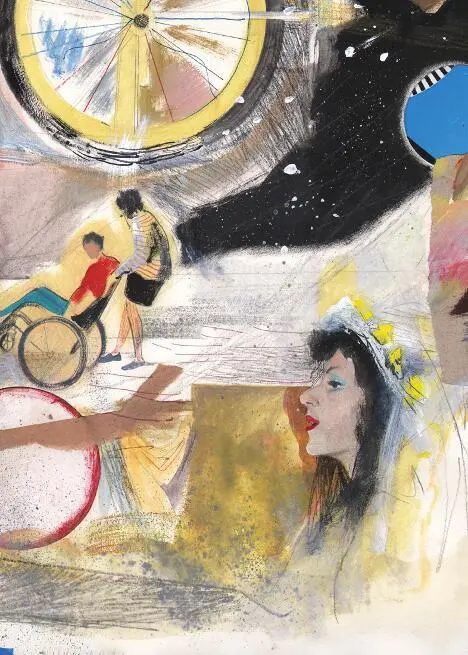

“YEAH, LIFE WERE GREAT ’ERE, when we was young, yeah, life were great when we’d got money, me even a million, I were a millionaire,” said Mr Svoboda, lying on his front in his little garden, with a stream running past him, with young willows and rows of blackcurrant and gooseberry bushes, Mr Svoboda was lying on his front next to a bed of parsnips, or rather he was lying on his side with his great belly lying next to him like a barrel, one arm like a pillow under his head and the free one weeding the weeds from the parsnip bed, the sun shining down on his unbelievably huge paunch, his breasts like a huge wet-nurse’s, with pendulous nipples, and Mr Svoboda, catching me looking at his frontage, said: “It’s not lard, it’s tallow, like what boars, wild boars have, but life were great ’ere, till it left through that gate,” he pointed to the broken hedge, rank with hazel and elder, and contentedly, as if he’d been telling himself the same story for the hundredth time, he carried on plucking out the weeds with his fat fingers, and when he’d weeded as far as his reach would allow, he raised himself up like a monstrous walrus and shifted himself on a bit and his body contentedly settled back down and Mr Svoboda carried on weeding and talking: “We used to amuse ourselves different from young people today, like the time I put an advert in the paper: ‘Wanted to buy: large guard-dog, travel expenses will be reimbursed.’ And my pal, he’s got that cottage on Dyke Road, above the pond in the forest, I mean Kožíšek the chemist, when he opened the blinds in the morning, he nearly fell flat, outside his chemist’s shop there was at least ten blokes with dogs, and Kožíšek asks: “What are you doin’ here?” And they said: “We’re here ’cos you advertised for a big guard-dog, so we’ve come,” and they showed him the ad, since he, my mate Kožíšek, didn’t believe ’em yet. Meanwhile more men arrived with more dogs an’ the dogs started fightin’ and bitin’ each other, so Kožíšek decided he would buy one, which he did, so as to be shot of the other dogs, but the dogs’ owners started shoutin’ about suin’ if they didn’t get their travel costs back as advertised, so Kožíšek had to pay not only their fares out here, and some came from as far away as Moravia and Vimperk, but also their travel back, but if you’ve got the money, you can afford to have fun, see?” And he added: “But Kožíšek repaid me twice over, he threw a big party and I had this stupid habit of always havin’ my pockets full of false teeth from their makers an’ I tossed one such mandible in Kožíšek’s coffee, ’cept he slipped his coffee my way an’ he drank mine, an’ I’ve got such a delicate stomach!” said Mr Svoboda and he stopped weeding, made a mooing noise and retched and puked something up with the memory of those wonderful years of his youth, buried it in soil with his great big paw and continued: “I drank it an’ the teeth got jammed in my mouth like some great fish bone an’ I started to choke, an’ I could easily have died, ’cos I weren’t expectin’ it, so I got my own back on Kožíšek when he were pukin’ outside the front into his rose bushes an’ I puked out of the window right down the back of his neck, so when he came in he were right surprised, an’ his wife was too, like how could anyone puke down the back of their own neck… like I say, we was young and when you’re young it’s time for fun.” And I nodded cheerily because I liked being with Mr Svoboda and his bare belly, and I liked listening to him talking, saying, artlessly and sincerely, all those things that one is more inclined to feel shame than pride at, and Mr Svoboda, seeing the admiration in my eyes, continued, slowly plucking out the weeds with his fat fingers, himself a very picture of endless contentment and ease: “But the biggest bastard’s my midget friend Eliáš, there’s no other candidate for the title… so one time, during the Protectorate, when cement was the Reich’s life-blood, I like an idiot thought, no, I wasn’t thinkin’, but I did get fifty bags of cement on the cheap an’ took it into my ’ead that ’ere, between the gate and the cottage door, there could be two strips, two cement walkways, just right for the wheels of a car or for people in the rain to walk up… an’ suddenly I gets this telegram, which said, in German: ‘Herr Svoboda, Kersko, Revision und Kontrolle ihrer Parzelle, Dienstag’, signed by SS Sturmbahnführer Habrman. So first I shat myself, then my wife shat herself, then we had an argy-bargy over who on earth had had the bright idea of the cement pavin’ for a car, then we shat ourselves again jointly, an’ I, all miserable, drove to Kersko and begged the mayor of Semice to loan me a couple of carts for the weekend, for which I’d pay him regally, an’ so all day Saturday an’ all day Sunday, I ’ad farmers fetch me soil, an’ I raked it out over the concrete tracks an’ slowly they disappeared, all fifty metres, an’ I was thinkin’, why hadn’t I built the cottage right next to the gate! An’ when I’d finished, I scattered pine needles on top of the soil, fortunately this was in the autumn, so I went back and forth fetchin’ and spreadin’ leaves like children at Corpus Christi, until there wasn’t a trace left, and come that Dienstag I waited, throwin’ up now an’ again, even though I’d had nothin’ to eat, kept retchin’ and pukin’, reduced finally to whimperin’ and bringin’ up no more than spit, too scared even to shit myself, didn’t have the wherewithal, just some green watery stuff… an’ I waited an’ that morning seemed like a week, an’ the afternoon another week, a fortnight’s fear I got through in a single day, but nothin’ happened… an’ suddenly it dawned, it was my mates what had done it to cheer me up, for a lark…,” said Mr Svoboda, heaving up his belly like a 200-litre barrel and pushing it slightly aside and backing up after it and puffing and smiling, though he’d paled at the recollection, and he went on: “… but I got my own back, the chemist, Kožíšek, ’e ’ad a garden like mine, back then we ’ad apples an’ we was amateur gardeners, an’ I offered to take ’is best apples to the flower an’ produce show an’ set up his table for him, an’ I ate all his apples and collected some windfalls and set ’em out an’ next to ’em I put the sign that ’ad been beautifully written by Kožíšek ’imself: James Grieve an’ Jonathan an’ Nonnetit… an’ so on, an’ at the corner of the table I puts a big, fancy sign: ‘From the garden of my friend Jan Kožíšek, Kersko’, an’ although there was fifty growers of fine fruit there, most people was clustered round my friend Kožíšek’s table, it were the sensation of the county show, a blockbuster, an’ when Kožíšek ’eard that most of ’is friends an’ other people was clustered round ’is table, ’e grabbed the family and took a carriage, that was a sight to see back then in Kersko, for a hundred crowns farmers would hitch up a carriage, oh, the carriage journeys we ’ad, legless, at night, by the light of the moon, by carriage all the way to Poříčany to catch the last train, the sidelamps lit up the horses’ back ends beautifully, young folk would stand, holdin’ onto the box, with one foot on the step an’ holdin’ bottles or flowers in their free hand, we’d ’ave the seats… but where was I? Kožíšek arrived at that memorable flower an’ produce show in the carriage with some flowers an’ his wife an’ he had to part the crowd clustered round his fruit, an’ as he stood there beamin’ over his windfalls with the whole place eruptin’ in laughter, Kožíšek suddenly shrunk by fifteen or twenty centimetres an’ his wife were burnin’ wi’ shame an’ embarrassment, an’ so they went back ’ome in utter misery, not by carriage this time, but by the back way, through gardens an’ along cart-tracks, back to Kersko… But that was because we was young an’ we’d got money, an’ when you’re young it’s time for fun, an’ to this day I get awful hungry, but back then, every time there were a pig-feast, I’d eat eighteen white puddin’s an’ three plates o’ goulash, I never even counted the black puddin’s ’cos I already weighed a hundred and thirty kilos. One time we was invited by Baroness Hiross to their huntin’ lodge, an’ while my friends was admirin’ the huntin’ trophies, I were sat at the dining table, then down the stairs comes the baroness wi’ my friends behind ’er, affected by ’er showing them ’istoric portraits of ’er and ’er husband’s ancestors, an’ from the stairs she says: “And now let me invite you to partake of a small collation,” but the table was empty an’ I were just stuffin’ myself with the last plate of fifty open sandwiches, one sandwich after another, but I were young an’ I’d got money, an’ the baroness took it in good part, ’cept there were no more food at the lodge, so she sliced some bread for my friends an’ spread drippin’ on it, Christ, I can feel the hunger even now, such wonderful hungry times they was, but I don’t have so much money these days, an’ even though I don’t get so hungry any more, I can really enjoy a whole salami sausage, salami that I hang in my toilet ventilation shaft to fine it, but I never leave it to get fully fined ’cos I always eat it whole the very first night after buyin’ one to fine, only once did I eat a fully fined salami, it was during the Protectorate and I’d got a whole Hungarian salami, anyway, I were comin’ in and saw, down in the basement below our flat in Prague, the concierge with a great chunk of salami in a vice, cuttin’ bits off it with an ’acksaw, an’ I could tell from the colour of it that the swine was slicin’ salami, so I ’eads straight down and says: “My mouth’s fair waterin’, ’ow much do you want for that salami?” an’ ’e says: “Two thousand,” so I gives him the money, but the salami really were that ’ard that you really did need an ’acksaw, so I gave ’im an extra two hundred an’ ’e ’acked it into rounds for me, I completely lost control an’ wolfed down each slice as he cut it off, until I wolfed down even the string at the end, ’cos there were this woman walkin’ past an’ I bent down to see up her skirt from down below in the basement an’ grabbed the last piece an’ that’s ’ow I ate the string as well,” said Mr Svoboda and he heaved up his mighty belly, plopped it back down and rolled over on his other side, his spine following his belly, then he switched hands and again put one massive paw — as thick as my leg — under his head, like a pillow against his ear, and with his free hand he weeded the bed of parsnips, slowly and totally engrossed in the task, as if he were extracting sharp needles, and he went on talking, quietly, dreamily and with a smile, revelling once again in his youth…, “an’ a week later it dawned! an’ there an’ then I ’eaded for the larder, an’ there an’ then I throttled the wife and then the maid, an’ in tears the maid said that, when they was ’avin’ a clear-out, they’d found a salami of sorts ’angin’ there, all mouldy and rotten, so she’d slung it in the bin in the yard, an’ just like Baron Hiross, who paid twice over an’ feasted on his own huntin’ dog as a moufflon, I paid twice for an ’Ungarian salami… but you, my friend, what I’m tellin’ you isn’t true, every week, before leavin’ for Kersko, I do fine a salami, salami fined off in the ventilation shaft ’as a special flavour, the draft takes warm air up from the central heatin’, an’ I really must fine a salami to perfection one day, an’ that takes a lot o’ will-power, but one day I will get the better o’ myself, one day I really will fine one to perfection, one day I’ll bring one all the way out ’ere so you can ’ave a taste an’ see what a delicacy it is, salami fined for a fortnight, like what I ate in Moravia… but I’ll bring it when you’re not hungry exactly, but you’ll still fancy somethin’… just for you I’ll buy a whole thirty-five crown salami, just for you I’ll hang it in the central heatin’ ventilation shaft, there’s a little hatch, see, in the toilet, like the one in a farm smokehouse, an’ that’s where I’ll fine it, except the moment I lie down, even on a full belly…, like when I’m on the way ’ome from work, I spend an hour in the shop, my bag’s full, an’ it’s a hundred grams of this salami an’ a hundred of that, an’ a hundred and fifty grams of Silesian brawn an’ two hundred of ordinary brawn an’ some mayonnaise an’ little pots of pickled fish, Russian sardines an’ rollmops, that’s ’ow I live, whenever I see ’em in a shop window, I get such an appetite an’ I weaken, so straight into the shop, an’ first I order a plateful to eat in, then I buy all sorts of cheeses, then it’s ’ome, not walkin’ but runnin’, an’ at ’ome we eat it all in front of the telly, an’ I keep reachin’ forward until there’s nowt left on the table, ‘So I’ve eaten it all,’ I says, then we go to bed, an’ I wake up at midnight an’ it’s like there’s this golden salami hangin’ from the ceiling before my very eyes, the salami that’s hangin’ in the draught in the ventilation shaft in the toilet, the salami glitters an’ gleams like crown jewels, an’ I shade my eyes, but the salami so seduces me with its beauty that I tells myself: ‘You’re finin’ it for your friends, you’re finin’ it for your friends,’ but on an impulse I gets up an’ ‘Bollocks!’ I says, an’ I goes into the toilet, cuts ’alf of it off an’ tucks into it there an’ then, to finish it off in bed, an’ the wife says, in ’er sleep: ‘Don’t get grease on the duvet…,’ then she sleeps on, I drop off as well, but an hour later I sees that fined salami again, the salami that’s only been being fined for less than a day, an’ I can’t ’old back an’ I get up, then I lie back down an’ I’m beginning to get the better of myself, a moment longer an’ I’ll overcome that cravin’, that urge to eat the rest of the salami, until, just when I thought I’d won, I let out a deep sigh an’ the wife half-rose an’ said: ‘Stop torturin’ yourself, Karel, eat the damn’ salami…,’ an’ havin’ waited all day, all night, I wolf down the rest of the salami, then I sleep like a loach…” Mr Svoboda carried on meticulously weeding the parsnip bed where he lay, the sun bobbed up over the pine trees and flushed the garden with the pre-noon heat of a glorious July day, and like a machine he pulled up tiny weed after tiny weed and loosened the soil round the parsnips to give them room to swell, because weeds know no greater delight than to strangle anything more noble, destroy everything they enclose and convert it into humus for their own benefit… “You mustn’t think…,” said Mr Svoboda gently, “it’s not unknown for me to buy an extra salami, so I’ve fined two at a time, I’d wolf one down in the night without finin’ it properly, but the other one — twice now — hung there the full fortnight, it must have been fully fined by then, it was a salami for you an’ my friends to taste what an ordinary long-life salami is like after it’s been fined, tastes like ’Ungarian salami, an’ twice I’ve set off with one in the car, but I got as far as Počernice an’ I had this vision of it danglin’ out of the sky on a string in front of the radiator, a gold salami fined by me, an’ just past Počernice I had to brake an’ shout ‘Bollocks!’ And the wife ’ad to say: ‘Stop torturin’ yourself, Karel, or you’ll crash…,’ an’ I lifted the bonnet an’ I took a knife an’ went an’ sat in the ditch, that disgustin’ gully behind the Počernice abbatoir, in among the stinkin’ vapours an’ old pots an’ a pile of shit here an’ there, but I really enjoyed wolfin’ down that salami an’ afterwards I could drive easy, an’ all the next week I was resolved to bring specially for you that other fined salami, and I did get further this time, I nearly won, but near Mochov I suddenly got so hungry that I weakened and the cravin’ were so strong that I started seein’ things, again the fined salami was danglin’ out of the sky on a golden string in front of the radiator, an’ again the wife says, me havin’ started to weave across the road: ‘Stop torturin’ yourself, Karel!’ An’ I stopped an’ hopped right into the ditch with the salami, that salami fined for a fortnight and meant specially for my friends… but next time I eat a salami, when I’ll ’ave got as far as Semice with a fined salami an’ eaten the whole thing there on the green, without bread, chopped into little cubes, after that, once I’ve slowly but surely got the better of myself, I will bring one all the way ’ere for you, ’cos from Semice to Kersko it’s no distance, though even havin’ got this far, I can’t vouch for myself, havin’ arrived with it, I’ll start soundin’ my horn at the edge of the forest, at Vicarage Lane, and you’ll ’ave to drop what you’re doin’ and come runnin’, because I can’t vouch for myself, if I got the fortnight-old fined salami out, I might dive right into it, there and then; before you can take it from me it might be inside me, ’cos though I don’t get so ’ungry as in the past, I do get cravin’s, and they can be more dangerous than your actual hunger…,” said Mr Svoboda and he raised himself up, knelt and set his belly on his knees, then quickly lifted his paunch and prised himself up from the knees with it, then stood upright, from behind Mr Svoboda looked slim, so erect and proud was he as he bore that vast, unbelievably huge belly before him, and his 130-kilo persona strode off in his glazed-cotton boxers — three metres of the fabric went on them — and as he strode over the stream, the footbridge sagged and Mr Svoboda turned and said gleefully: “Right, I’m off now, an’ before I start weedin’ the carrots I’m goin’ to polish off a whole long-life sausage that I’ve got ready for finin’ and bought yesterday in Semice…” I said: “Why torture yourself, Mr Svoboda…” And, contented, Mr Svoboda withdrew through the greenery beneath his fruit trees and on past the trunks of Goldilocks pines to enter his cottage with its green shutters, and I used to see him every Easter, doing the rounds on Easter Monday with his friends, who deliberately let him carry their baskets of eggs, and at every cottage and every chalet they’d get eggs a-plenty, because everyone looks forward to Mr Svoboda coming, and they’re honoured to be able to treat the visitors to dozens of sandwiches, and Mr Svoboda rewards them with his wonderful account of fining salamis, stories that everyone knows already, but every Easter Monday the people in their cottages in the forest look forward to hearing them again. They love to see how, after the thirty or forty sandwiches he’s eaten in the thirty cottages and chalets, he can still manage more, and his appetite is at its height when, at the back of the procession of carollers and brandishing his randy-pole decorated with red and blue ribbons, Mr Svoboda can down eggs whole, shell and all. And each time his carolling friends say: “Karel, didn’t you just swallow a whole egg?” And Mr Svoboda, Easter caroller, gulps and says: “Me?” And his friends say: “Come on, open your gob!” And Mr Svoboda opens his huge mouth, and it’s empty, the egg’s already gone to join the dozens of other painted eggs down inside his stomach… Right now, though, with Mr Svoboda gone off in his glazed-cotton boxers that took three metres of cloth to make, it came to me that the man who’d gone off was a king. I’d noticed that Mr Svoboda had wonderful hair, as thick and curly as Africans’, one little curly wire after another, clinging to his head like a helmet of curls. Mr Svoboda is actually quite a dazzler, and so a king.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Rambling On: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Rambling On: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Rambling On: An Apprentice’s Guide to the Gift of the Gab» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.