Anton knows an awful lot. But he doesn’t know everything. For example, he told me that girls don’t have pricks.

— Then how do they pee? I asked.

He thought for a while, then shrugged his shoulders.

— Out their ass, I guess.

I found this weird. I was too scared to ask my mom. Moms don’t like to talk about things like that. And I never thought to ask my dad. Some things you just can’t talk about.

There are two girls who live in our street and who aren’t annoying. I asked one of them when she was outside skipping.

— How do girls pee?

She looked at me like I was the stupidest boy in all the world.

— Anton says that girls pee out their butts, I added.

— Tony Terylene? she asked, making a face as though he’s a dubious source of information.

— Yes.

— Girls don’t pee out their butts. Are you being a stupid jerk?

— Then how do girls pee?

— They pee out their pee-holes.

I went directly to Anton with this new information. As soon as he came to the door, I whispered:

— They pee out their pee-holes.

— Pee-holes?

— Yes, I said, with the air of one who knows everything.

Mostly, I was glad to finally know something he didn’t know.

— What’s a pee-hole?

I didn’t know. I ran back, but the girl was gone.

Sometimes Dad gets sent pictures of men. They’re large, thick-framed pictures. The men always look pissed; they wear black clothing, and often have a black hat. They’re really old. I know that some of the men are officers in the Soviet Union. Sometimes there are pictures of them in the papers, usually standing on a balcony and waving to a crowd of people with flags. The men are the complete opposite of the people. The people are super happy, but the men don’t smile. I don’t understand how that’s possible. Why are the men always so serious? Why aren’t they as happy as the people with flags? And why are there always soldiers and tanks in the center of the towns?

When the pictures come, it starts an argument between my parents. Dad wants to hang the pictures up in the living room along with the family photos. Mom puts her foot down.

— Why not?

— Because it is totally out of the question!

— I can’t put up a picture I’ve been given?

— No.

— Can I hang it in the television room?

— Not a chance.

— Why not?

— Because it’s absurd.

— Absurd? What’s absurd about it?

— If you can’t see it yourself then I won’t discuss it with you.

— It’s a gift for me.

— Enough of this damn prattle! You’re not hanging this picture; we’re done talking about it.

Mom always has the last word. She’s the decider. And since my dad doesn’t get to hang the pictures up in the living room, he hangs them up down in the basement. Hanging there are the comrades Gromyko, Brezhnev, Khrushchev, and Stalin, watching each other with their grave expressions.

There’s a horrible man in the living room. He’s wearing bright red clothes and has a long, white beard. I try to clamber up my Dad’s leg. He just laughs and turns me back to face the man. He looks at me, says something and stretches out his hands. He tries to take me. I get scared and start crying. Mom comes and picks me up. She walks me over to the man. He holds his hat towards me in one hand. I scream in terror, smear myself against Mom, and bury my face in her shoulder.

We’re in the living room. I’m not allowed to get into the Christmas presents. I’m not to play with any of the Christmas stuff. It’s for decoration. It’s dangerous. My dad is wearing his police uniform. He gives me a present. There’s another cop with him. They’re happy.

— This is for you, he says, in a friendly manner.

He has a gentle expression. I’ve already got the present. I’m allowed to open it.

In the package is a red truck. It’s mine. There are barrels on the truck bed.

When I’m playing, Mom comes over with other packages and gives them to me. I don’t want them.

— I’m ready to go out, I say.

— You can have this, too.

I don’t want it.

— I am ready to go out.

Mom smiles. She smiles beautifully.

She dresses me in my raingear.

— Shall we go to Róló? she asked.

I nod. Róló is a place with playground equipment and a fence around it. There are swings and a seesaw and a giant sandbox with iron hollows that you can sit in and shovel with. There are kids there to play with.

I have on red rain pants and a blue rain jacket. Mom also puts me in black boots, hat, and gloves. Then we walk to the playground.

It’s always raining at Róló. Mom often takes me there and leaves me. I have everything I need there. I own the swings and seesaw. I also own the hut. The other kids can play on them, sure, but only if they ask for permission. If someone tries to play without asking for permission then I pull his hair and he begins to cry.

I also own one of the boys at the playground. He is called Ragnar. He doesn’t need to ask for permission because I own him.

Once time, Ragnar and I ran away from the playground. We set car tires up against the fence and climbed over when the women weren’t looking. We ran away. We got lost. There were lots of cars. First Ragnar started crying and then I did. Then I closed my eyes and lay down. We’ve never done it again.

Sometimes I go over to where the women are. They sit and smoke. They wipe my nose and give me sugar cubes.

My sister Runa comes to fetch me. My mittens have got wet. They have a strange smell when they get wet; you can drink water from them by sucking them. She undresses me out of my rain pants and boots. The boots are stuck to the rain pants with elastic. She holds them and makes them walk. That’s funny.

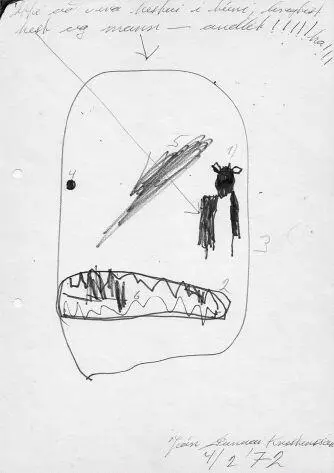

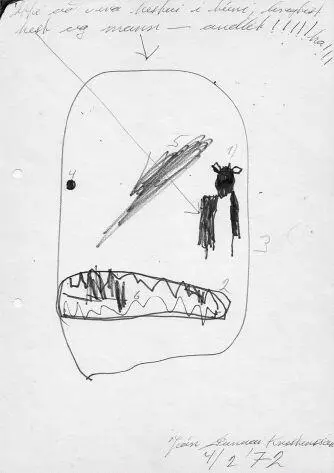

Drawn by Jón in the hospital at age 5 on 02/04/1972, with notes from the doctor: “Was supposed to be a horse in a meadow, changed into a horse and a man — face!!!! what!!!”

[…] This nearly 3-year-old boy was admitted because of

hernia inguinalis

; it had lasted for the past 2 months. He has always been plucky but also extremely rowdy, perhaps as a result of a hyperkinetic disorder; he is never calm around objects, but gets agitated and rages at everything.

(St. Joseph’s Hospital,

Landakoti, 10/02/1969)

…In the summer of 1969, Jón Gunnar was in preschool; he was considered unruly and rowdy but not especially problematic; he truly enjoyed school. This was, however, only for the summer. In the fall of 1970, he was a kindergartener in a little residential area, but the women employed there gave up on him. He did everything “madly.”

(National Hospital, Psychiatric Ward,

Children’s Hospital Trust, 02/04/1972)

I give my mother the slip. She calls and I don’t answer. She’s annoying and I don’t want to be around her. I run as fast as I can. I’m going to hide so I look for a hiding place. Mom calls for me again. But there’s nowhere to hide, just big streets and cars.

I run out into the road. A large car honks at me and I startle. I didn’t notice it. It just came out of nowhere. I jump onto a traffic island. Cars rush past on either side of me. I can’t run back across the street. The cars come towards and away from me no matter which way I turn. I’m stuck. I’m afraid, too.

Читать дальше

![О Генри - Бабье лето Джонсона Сухого Лога [The Indian Summer of Dry Valley, Johnson]](/books/407344/o-genri-babe-leto-dzhonsona-suhogo-loga-the-india-thumb.webp)