I can’t see properly when I come back into the gym. It’s pretty dark. I can’t see anyone well enough to recognize faces. I don’t want to draw attention to myself; I try not to squint. I walk nonchalantly along the bars, feeling my way through the air with my hands. I’m hoping I’ll come across Ásta. I try to fumble my way to where I last saw her. I hug the walls as I go, running my hand through my hair for reassurance. I feel the earrings, which are dangling loosely in my ears. I barely touch them. They hurt.

It’s hot in the room and brilliantine is streaming down my face again. My eyes burn and I can’t help weeping. This doesn’t help my vision. I bury my face in my collar, rubbing away the revolting lard. Between the myopia, the tears, and the lard, I can’t see a thing. The smarting’s getting more intense. I can’t bear it. I rub my eyes. I’m filthy with brilliantine. I’ve got to head back to the bathroom. I’ve got to rinse my eyes and clean myself up.

I can’t see the door. I can’t find my way back. I hear some kids laughing. I hope they aren’t laughing at me. I hope no one can see me. I walk away.

Suddenly, the lights are turned on. I can see a little better. My eyes burn and smart. I reach into my pocket and get my glasses. I need to get to the bathroom. I hope Ásta can’t see me.

— Oh my good God! What have you been doing?

I put my glasses on. Ingibjörg is standing in front of me. Her face wears an expression that’s equal parts astonishment and worry. All around me, kids are standing silently and staring at me. I try to act manly.

— I was just stepping out.

She takes me firmly by the hand and leads me away. She orders the kids to remain inside the gym.

We go into the bathroom. The sight that greets me in the mirror isn’t pretty. My neck and ears are covered in blood. My ear lobes have swollen to triple their normal size. My face is flooded with fat, sticky tears. My eyes are puffy and red and swollen. I rinse them in warm water.

— Is he okay? a girl asks. It’s not Ásta.

— Yes, yes. Go back in, replies Ingibjörg.

I feel better. I dry my face and snort up through my nose. I daren’t touch my ears. It’s like the skin has been peeled off them. I’m bleeding from both lobes.

— What happened to your ears? asks Ingibjörg

— They’re earrings.

— Who did this to you?

— I did it myself.

— With what?

I show her the haggis needle.

— Oh my God!

Ingibjörg drives me home. This sucks. It wasn’t supposed to happen this way. I’m not cool. I’ll never be a hotshot. I’m a moron. I always do everything wrong. I can’t ever do anything right. I’m not like other guys. I’ve got red hair and I’m ridiculous. I can’t play sports. I’m a half-wit who can’t learn. Everything about me is ugly and disgusting. No girl will ever have a crush on me. Other kids have siblings and enjoyable home lives. Other families go traveling and do things together. We never do anything. And when Mom and Dad go somewhere, I can’t come. For me, home is always majorly weird. My dad is a weirdo. He isn’t like other dads. You couldn’t even call him grandfatherly. If I try to talk to him, try to tell him something, he stops me and corrects me or mimics the way I talk. Okay, I do “ehhh” and “uhhhh” a lot when I’m saying something.

— Do you really need to say ehhh so often when you talk?

But I never say ehh or uhh so much as when I’m talking to my dad. If he can’t work out what I’m saying, he moves on to something else, stops listening to me, focuses all of a sudden on my fingers.

— Are you still biting your nails?

I get distracted and look at my fingers. They’re bitten down to the quick. Sometimes I bite them so much they bleed. I bite my nails, the skin around them, even my cuticles. Sometimes the wound festers. I don’t know why I do that. I always have done. I’ve tried to stop but I can’t. I immediately forget and start biting again. I do it unconsciously.

— Yes.

He takes me by the hand, hard.

— Didn’t you promise me you’d stop with this?

I don’t have anyone to talk to. Nobody tells me anything. No one cares about me. I’m like Rubber Tarzan. I’m all alone in the world.

Jón Gunnar […] has proved very stubborn and rebellious, so much so that his parents, who are quite elderly, have largely given up on raising their child […] He often ends up in conflicts with other children, is on the one hand too controlling and the other hand afraid. His physical and his EEG were normal. Psychological tests and observations reveal that the boy is highly intelligent. He suffers from a considerable castration anxiety, he concocts some pretty extraordinary outlets for his aggression, and he flees his anxieties most uneasily. His sense of reality is good and his ability for sympathetic insight is not in any way compromised. In most aspects of his psyche, he’s developed naturally.

He finds that his environment has turned chaotic but lacks the means and ability to change that. There doesn’t seem to be any doubt that the parents have grown too elderly to cope with raising such an unusually energetic boy. They have effectively given up and the child has taken charge to a pronounced degree, so much so that his security is at risk.

Diagnosis:

maladaptio.

(National Hospital, Psychiatric Ward,

Children’s Hospital Trust, 09/06/1972)

It’s like something’s not right. Why can’t I be like everyone else? What’s up with me? I’m no good at anything, not school, not sports, not social activities. I don’t even have good taste in music. What others find easy and natural, I find complicated and alien. Everything I try to do fails or breaks. And there’s no one else to blame. There’s something wrong with me but I do not know what it is. I’m abnormal. I’ve nothing in common with anyone. I’m ugly, stupid, and annoying. Maybe I’ve been cursed. Everyone else has normal hands. My hands are always dirty, the nails bitten down past the tips. I’m embarrassed that I bite my nails, but I cannot stop.

The future scares me. Everyone’s headed somewhere together and I’m not invited. I’ll go alone, somewhere else. I don’t know where. I never know anything; I’m unable to do anything. No one cares about me at all. I’m all alone in the world.

I’m an Indian.

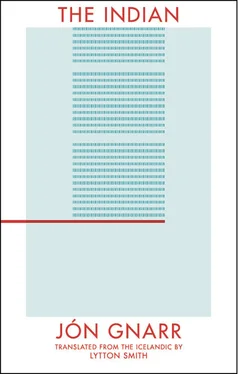

I am translating The Indian , revisiting my childhood as the book’s young narrator eagerly reads something his mother has bought for him — just the way I was as a kid. Mér finnst gaman að Andrési. My literal translation — what translators call a trot — would read Me feels/finds good/fun in Andrew/Andrés . Something like “I enjoy Andrew a lot.”

I’m at a loss. “Andrési” is not an Icelandic name. And, several lines down, I find “Onkel Joakim” and the “Björnebanden.” Uncle Joachim? The “Bear-band” or “Confederacy of bears?” The context tells me this is a child’s comic strip, but my knowledge of 1970s Icelandic comics — limited, I confess — is being severely tested.

It takes an internet search to realize, via the Danish Bjørne-banden , that these last characters are the Beagle Boys, the hapless dog-like criminals I laughed at in the Duck Tales of my youth. Uncle Joachim? Scrooge McDuck. Andrés, or Andrés Önd, is not Andrew Duck, but Donald Duck, his name changed to preserve alliteration in translation.

Comics were when I first noticed translation, reading my way through Goscinny and Uderzo’s Astérix series, about a small, unconquerable Gaul and his corpulent, near-invincible menhir-delivering sidekick, Obelix. And not to forget Obelix’s indomitable terrier companion, Dogmatix! The dogmatic dog — a wonderful pun.

Читать дальше

![О Генри - Бабье лето Джонсона Сухого Лога [The Indian Summer of Dry Valley, Johnson]](/books/407344/o-genri-babe-leto-dzhonsona-suhogo-loga-the-india-thumb.webp)