— Have you gone berserk, child?!

I can no longer see. My eyes are full of tears. I hear only a buzzing sound. I flail and kick in every direction and scream as loud as I can, again and again.

— Motherfucker, motherfucker. I’ll kill you, you motherfuckers!

The farmer has a wooden leg and walks with a stick. He’s annoying. So is his wife. They have two adult daughters, called Laufey and Erna.

Erna’s all right. She often talks to me. She lends me books, too. Otherwise, I’m not allowed to borrow books because I might damage them. But Erna stole some for me: Tarzan and Anna from Stóruborg . They’re fascinating books.

Laufey’s nothing but a grown-up. She hardly speaks to me.

This farm is different from the one I went to before. It’s evil being here. Everyone talks in an ugly way and says ugly things. They’re also always in a foul temper. I feel uncomfortable around them. I’m scared of them.

All the same, I don’t have to eat any more food than I want to. No one forces me to eat. That’s good, because they eat tons of revolting things.

Once I came into the kitchen and peeked into the pot to see what was for dinner. I jumped back, startled. In the boiling water stood four teats. Boiled udders! That night, the farmer ate them.

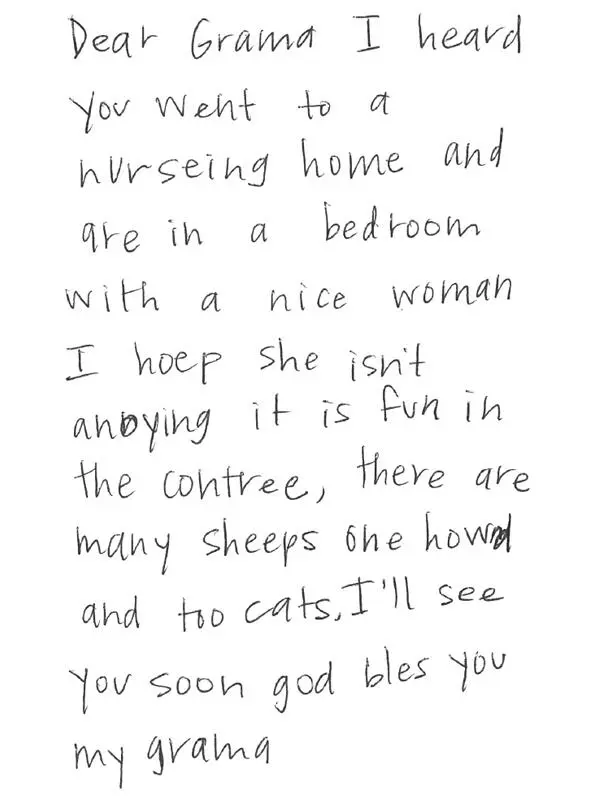

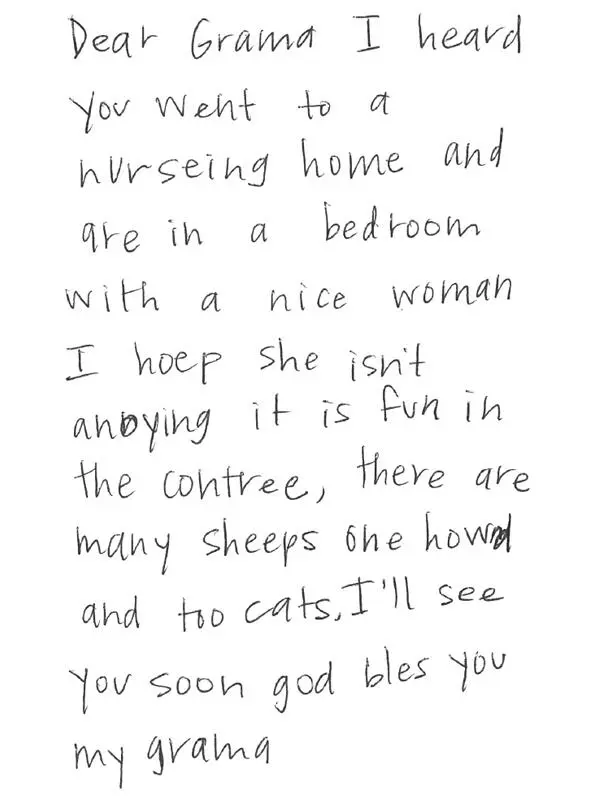

As soon as I went to the countryside Grandma went into a nursing home. Soon after I arrived, I wrote her a letter:

On the farm, there’s a workman called Skúli. He’s a man of few words. He leaves early in the morning to repair the fences and drive the tractor. Usually he’s on his own, but sometimes I get to go along to help him. I like being with him. He doesn’t say anything.

Once, I was ill. I told the farmer’s wife.

— I don’t listen to the devil’s gossip. Nothing wrong with you but laziness. Get out of bed right now and go help Skúli outside.

I dare not do anything but obey. But I really was ill.

It was raining outside, and cold. I helped Skúli for a little while until I threw up. Skúli took me home and chewed out the woman. It’s the only time I’ve heard him say something.

— This is more of your bloody folly, you old bat! Why send this wretched boy out when he’s so sick?

— I thought he was simply being lazy.

— He’s very ill; he’s got a fever. He threw up while putting hooks in for the barbed wire.

— I didn’t know.

— That’s because you’re so busy being bossy.

He went back out, slamming the door behind him. The woman looked at me.

— Crawl back into bed, you!

When I first got there, there was a young girl on the farm. She was handicapped in some way. She left soon. I think it was because she yelled a lot. Sometimes she screamed at night. I’d hear the farmer yell back.

— Stop your wretched howling, you imbecile!

When I had been on the farm for a few weeks I called Mom. I started crying when I talked to her.

— I don’t want to be here, I whimpered.

— There, there. Don’t be like that.

— Come fetch me.

— It can’t be that bad.

— It is.

— Isn’t there a dog on the farm? You can play with it.

— No, I want to come home.

— Be a good boy.

She wouldn’t listen to me. I wept so hard that I could not speak for sobs and snot. The farmer’s wife took the phone and reassured my mother that I was okay.

— You know, he’s just a little keyed-up. He needs some fresh air.

A week later, I got a card from Mom. Inside she’d written: Darling son. It’s good that you’re enjoying the countryside.

I broke down and started crying. I’d never felt so alone in the world. No one cared about me and certainly not about how I was getting on.

I have to help out, here. I help with the housework and also stuff outside. I get the cows and drive them into the field after milking. I drive them from the hayfield, too. That’s the most difficult thing to do. The sheep run so fast and they hide in the ditches.

— Jón, there’s a skjátur in the hayfield, the farmer says.

Skjátur are sheep. I go out and look across the hayfield behind the farm. I don’t see any sheep so I go back inside.

Everyone can see better than me.

— I don’t see a sheep.

He lumbers to his feet, muttering curses.

— Damn, hellfire, Jesus.

I follow him across the farm.

— There, he says angrily, and points.

If I squint my eyes I can see better. I still don’t see any sheep.

— Aren’t there just cows? I ask.

— Don’t talk to me about cows. Are you a moron, boy?

I don’t see any sheep. I’ve no idea where to head. The hayfield is massive. I stand, rooted to the spot, and wait. He hits me in the back with a mighty blow.

— Are you being damn insolent?

— No.

— Get the hell on with it, then, you miserable idiot boy!

He lifts up his staff like he’s going to beat me. I run away across the field. The grass is tall and wet.

Eventually, I see the sheep. There are two lambs. When they see me approach, they run away. They can run much faster than me. They hide, and I lose them again.

I stop and try to figure out where each of them has gone. It’s like the earth has swallowed them. Perhaps they’re lying down in a ditch or kneeling in the high grass. It’s like they’re invisible.

The devil-farmer is still standing on the side of the meadow. I’m so far away I cannot see him but I hear him screaming.

— Damn it, you bloody fool of a boy! Get the hell on with it! Get the hell after the sheep!

I run back to where I came from and try to spot them. I scurry back and forth, stopping occasionally to peer about. I see something and run towards it. It’s nothing. Perhaps they’ve headed back the way they came.

— I think they’ve gone back! I call across the hayfield.

He doesn’t answer. He’s probably gone back inside. That means the sheep are definitely back where they’re meant to be.

The tractor’s driving along the lane beside the farm. Someone depresses the gas pedal hard, fast, and repeatedly. That heats the engine. It’s probably Skúli, the laborer.

I watch the side of the tractor. Skúli must be coming to repair the fence so the sheep won’t escape again.

I walk over to meet him. I like helping Skúli. We knock down poles, make fences, and fix them, too. I get to remove hooks with pliers and nails with a hammer.

I’m getting my feet soaking wet in the grass. But that’s okay. It’s not cold. I’ll dry off in the sun.

The tractor draws near. I realize it’s not Skúli. It’s the farmer. He’s pissed.

— You’re a damned indolent idiot!

— They’ve gone. They went all by themselves, I say, trying to explain.

— Good-for-nothing! Do you want me to beat you, you devil-spawn?

He drives towards me.

He swings his staff, and swings it in my direction. I hear it whine past my ear. I get scared. I start to cry. I hate this man. I’m afraid of him. He could hit me with his staff. I’ve seen him hit the dog in the hall. He waves the staff around him so that it swishes. I hate this shitty farm and everyone on it.

— Piss off, you worthless waste of space!

I run towards him and grab the staff. I smack him with the staff. The blow is clumsy and he blocks it with his hands.

— Go to hell, grave-dodger!

Читать дальше

![О Генри - Бабье лето Джонсона Сухого Лога [The Indian Summer of Dry Valley, Johnson]](/books/407344/o-genri-babe-leto-dzhonsona-suhogo-loga-the-india-thumb.webp)