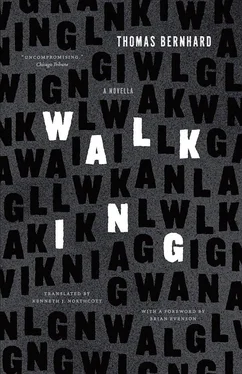

Thomas Bernhard - Walking - A Novella

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Thomas Bernhard - Walking - A Novella» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: University of Chicago Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Walking: A Novella

- Автор:

- Издательство:University of Chicago Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Walking: A Novella: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Walking: A Novella»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

); “a virtuoso of rancor and rage” (

). And although he is favorably compared with Franz Kafka, Samuel Beckett, and Robert Musil, it is only in recent years that he has gained a devoted cult following in America.

A powerful, compact novella,

provides a perfect introduction to the absurd, dark, and uncommonly comic world of Bernhard, showing a preoccupation with themes — illness and madness, isolation, tragic friendships — that would obsess Bernhard throughout his career.

records the conversations of the unnamed narrator and his friend Oehler while they walk, discussing anything that comes to mind but always circling back to their mutual friend Karrer, who has gone irrevocably mad. Perhaps the most overtly philosophical work in Bernhard’s highly philosophical oeuvre,

provides a penetrating meditation on the impossibility of truly thinking.

Walking: A Novella — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Walking: A Novella», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Oehler told Scherrer, among other things, that their, Oehler’s and Karrer’s, going into Rustenschacher’s store was totally unpremeditated, we suddenly said, according to Oehler, let’s go into Rustenschacher’s store and immediately had them show us several of the thick, warm and at the same time sturdy winter trousers (according to Karrer). Rustenschacher’s nephew, his salesman, Oehler told Scherrer, who had served us so often, pulled out a whole heap of trousers from the shelves that were all labeled with every possible official standard size and threw the trousers onto the counter, and Karrer had Rustenschacher’s nephew hold all the trousers up to the light, while I stood to one side, the left-hand side near the mirror, as you look from the entrance door. And as was his, Karrer’s, way, as Oehler told Scherrer, Karrer kept pointing with his walking stick and with greater and greater emphasis at the many thin spots that are revealed in these trousers if you hold them up to the light, Oehler told Scherrer, at the thin spots that really cannot be missed, as Karrer kept putting it, Oehler told Scherrer, Karrer simply kept saying these so-called new trousers, Oehler told Scherrer, while having the trousers held up to the light, and above all he kept on saying the whole time: these remarkably thin spots in these so-called new trousers, Oehler told Scherrer. He, Karrer, again let himself be carried away so far as to make the comment as to why these so-called new trousers — Karrer kept on saying so-called new trousers, over and over again, Oehler told Scherrer — why these so-called new trousers, which even if they were new, because they had not been worn, had nevertheless lain on one side for years and, on that account, no longer looked very attractive, something that he, Karrer, had no hesitation in telling Rustenschacher, just as he had no hesitation in telling Rustenschacher anything that had to do with the trousers that were lying on the counter and that Rustenschacher’s nephew kept holding up to the light, it was not in his, Karrer’s, nature to feel the least hesitation in saying the least thing about the trousers to Rustenschacher, just as he had no hesitation in saying a lot of things to Rustenschacher that did not concern the trousers, though it would surely be to his, Karrer’s, advantage not to say many of the things to Rustenschacher that he had no hesitation in telling him, why the trousers should reveal these thin spots that no one could miss in a way that immediately aroused suspicion about the trousers. Karrer told Rustenschacher, Oehler told Scherrer, these very same new, though neglected, trousers which for that reason no longer looked very attractive, though they had never been worn, should reveal these thin spots, said Karrer to Rustenschacher, as Oehler told Scherrer. Perhaps it was that the material in question, of which the trousers were made, was an imported Czechoslovakian reject, Oehler told Scherrer. Karrer used the term Czechoslovakian reject several times, Oehler told Scherrer, and actually used it so often that Rustenschacher’s nephew, the salesman, had to exercise the greatest self-control. Throughout the whole time we were in Rustenschacher’s store, Rustenschacher himself busied himself labeling trousers, so Oehler told Scherrer. The salesman’s self-control was always at a peak from the moment that we, Karrer and I, entered the store. Although from the moment we entered Rustenschacher’s store everything pointed to a coming catastrophe (in Karrer), Oehler told Scherrer, I did not believe for one moment that it would really develop into such a, in the nature of things, hideous catastrophe for Karrer, as Oehler told Scherrer. However, I have observed the same thing on each of our visits to Rustenschacher’s store, as Oehler told Scherrer: Rustenschacher’s nephew exercised this sort of self-control for a long time, for the longest time, and in fact exercised this self-control up to the point when Karrer used the concept or the term Czechoslovakian reject. And Rustenschacher himself always exercised the utmost self-control during all our visits to his business, up to the moment, as Oehler told Scherrer, when Karrer suddenly, intentionally almost inaudibly but in this way all the more effectively, used the term or the concept Czechoslovakian reject. Every time, however, it was the salesman and Rustenschacher’s nephew who first objected to the word reject, as Oehler told Scherrer. While the salesman, in the nature of things, in an angry tone of voice said to Karrer that the materials used in the trousers lying on the counter were neither rejects nor Czechoslovakian rejects but the very best of English materials, he threw the trousers he had just been holding up to the light onto the heap of other trousers, while Karrer was saying that it was all a matter of Czechoslovakian rejects, and made a move as if to go out of the store and into the office at the back of the store. It was always the same, Oehler told Scherrer: Karrer says, as quick as lightning, Czechoslovakian rejects, the salesman throws onto the heap the trousers that had just been held up and says angrily the very best English materials and makes a move as if to go out of the store and into the office at the back of the store, and in fact takes a few steps, as Oehler told Scherrer, toward Rustenschacher, but stops just in front of Rustenschacher, turns around and comes back to the counter, standing at which Karrer, holding his walking stick up in the air, says I have nothing against the way the trousers are finished, no I have nothing against the way the trousers are finished, I am not talking about the way the trousers are finished but about the quality of the materials, nothing against the workmanship, absolutely nothing against the workmanship. Understand me correctly, Karrer repeats several times to the salesman, as Oehler told Scherrer, I admit that the workmanship in these trousers is the very best, said Karrer, as Oehler told Scherrer, and Karrer immediately says to Rustenschacher’s nephew, besides I have known Rustenschacher too long not to know that the workmanship is the best that anyone could imagine. But he, Karrer, could not refrain from remarking that we were dealing here with trouser materials, quite apart from the workmanship, with rejects and, as one could clearly see, with Czechoslovakian rejects, he simply had to repeat that in the case of these trouser materials we are dealing with Czechoslovakian rejects. Karrer suddenly raised his walking stick again, as Oehler told Scherrer, and banged several times loudly on the counter with his stick and said emphatically: you must admit that in the case of these trouser materials we are dealing with Czechoslovakian rejects! You must admit that! You must admit that! You must admit that! Whereupon Scherrer asks whether Karrer had said you must admit that several times and how loudly, to which I replied to Scherrer, five times, for still ringing in my ears was exactly how often Karrer had said you must admit that and I described to Scherrer exactly how loudly. Just at the moment when Karrer says you must admit that! and you must admit that gentlemen, and you must admit gentlemen that in the case of the trousers that are lying on the counter we are dealing with Czechoslovakian rejects, Rustenschacher’s nephew again holds one of the pairs of trousers up to the light and it is, truth to tell, a pair with a particularly thin spot, I tell Scherrer, Oehler says, twice I repeat to Scherrer: with a particularly thin spot, with a particularly thin spot up to the light, I say, says Oehler, every one of these pairs of trousers that you show me here, says Karrer, Oehler tells Scherrer, is proof of the fact that in the case of all these trouser materials we are dealing with Czechoslovakian rejects. What was remarkable and astonishing and what made him suspicious at that moment, Oehler told Scherrer, was not the many thin spots in the trousers, nor the fact that in the case of these trousers we were dealing with rejects, and actually Czechoslovakian rejects, as he kept repeating, all of that was basically neither remarkable nor surprising and not astonishing either. What was remarkable, surprising, and astonishing was the fact, Karrer said to Rustenschacher’s nephew, as Oehler told Scherrer, that a salesman, even if he were the nephew of the owner, would be upset by the truth that was told him, and he, Karrer, was telling nothing but the truth when he said that these trousers all had thin spots and that these materials were nothing but Czechoslovakian rejects, to which Rustenschacher’s nephew replied, as Oehler told Scherrer, that he swore that in the case of the materials in question they were not dealing with Czechoslovakian rejects but with the most excellent English materials, several times the salesman swore to Karrer that in the case of the materials in question they were dealing with the most excellent English materials, most excellent, most excellent, not just excellent I keep on repeating, Oehler told Scherrer, again and again most excellent and not just excellent, because I was of the opinion that it is decisive whether you say excellent or most excellent, I keep telling Scherrer, actually in the case of the materials in question we are dealing with the most excellent English materials, says the salesman, Oehler told Scherrer, at which the salesman’s, Rustenschacher’s nephew’s, voice, as I had to keep explaining to Scherrer, whenever he said the most excellent English materials, was uncomfortably high-pitched. If Rustenschacher’s nephew’s voice is of itself unpleasant, it is at its most unpleasant when he says the most excellent English materials, I know of no more unpleasant voice than Rustenschacher’s nephew’s voice when he says the most excellent English materials, Oehler told Scherrer. It is just that the materials are not labeled, says Rustenschacher’s nephew, that makes it possible to sell them so cheaply, Oehler told Scherrer. These materials are deliberately not labeled as English materials, clearly to avoid paying duty, says Rustenschacher’s nephew, and in the background Rustenschacher himself says, from the back of the store, as Oehler told Scherrer, these materials are not labeled so that they can come onto the market as cheaply as possible. Fifty percent of goods from England are not labeled, Rustenschacher told Karrer, I told Scherrer, says Oehler, and for this reason they are cheaper than the ones that are labeled, but as far as the quality goes there is absolutely no difference between goods that are labeled and ones that are not. The goods that are not labeled, especially in the case of textiles, are often forty, very often even fifty or sixty, percent cheaper than the ones that are labeled. As far as the purchaser, above all the consumer, is concerned it is a matter of complete indifference whether he is using labeled or unlabeled goods, it is a matter of complete indifference whether I am wearing a coat made of labeled, or whether I am wearing a coat made of unlabeled materials, says Rustenschacher from the back of the store, Oehler told Scherrer. As far as the customs are concerned we are, of course, dealing with rejects, as you say, Karrer, says Rustenschacher, so Oehler told Scherrer. It is very often the case that what are termed Czechoslovakian rejects, and declared as such to the customs authorities, are the most excellent English goods or most excellent goods from another foreign source, Rustenschacher said to Karrer. During this argument between Karrer and Rustenschacher, Rustenschacher’s nephew kept holding up another pair of trousers to the light for Karrer, Oehler says to Scherrer. While I myself, so Oehler told Scherrer, totally uninvolved in the argument, was leaning on the counter, as I said totally uninvolved in the argument between Karrer and Rustenschacher. The two continued their argument, Oehler told Scherrer, just as if I were not in the store, and it was because of this that it was possible for me to observe the two of them with the greatest attention, in the process of which my main attention was, of course, focused on Karrer, for at this point I already feared him, Oehler told Scherrer. Once again I tell Scherrer, if you look from the entrance door, I was standing to the left of Karrer, once again I had to say, in front of the mirror, because Scherrer no longer knew that I had already told him once that during our whole stay in Rustenschacher’s store I was always standing in front of the mirror. On the other hand, Scherrer did make a note of everything, according to Oehler, he even made a note of my repetitions, said Oehler. It was obviously a pleasure for Karrer to have all the trousers held up to the light, but having all the trousers held up to the light was nothing new for Karrer, and he refused to leave Rustenschacher’s store until Rustenschacher’s nephew had held all the trousers up to the light, Oehler told Scherrer, basically it was always the same scene when I went to Rustenschacher’s store with Karrer but never so vehement, so incredibly intense, and, as we now know, culminating in such a terrible collapse on Karrer’s part. Karrer took not the slightest notice of the impatience, the resentment, and the truly incessant anxiety on the part of Rustenschacher’s nephew, Oehler told Scherrer. On the contrary, Karrer put Rustenschacher’s nephew the salesman more and more to the test with ever new sadistic fabrications conspicuously aimed at him. Rustenschacher’s nephew always reacted too slowly for Karrer. You react too slowly for me said Karrer several times, says Oehler to Scherrer, basically you have no ability to react, it is a mystery to me how you find yourself in a position to serve me, how you find yourself in a position to work in this truly excellent store of your uncle’s, Karrer said several times to Rustenschacher’s nephew, Oehler told Scherrer. While you are holding two pairs of trousers up to the light, I can hold up ten pairs, Karrer said to Rustenschacher’s nephew. How unhappy Rustenschacher was about the argument between Karrer and his, Rustenschacher’s, nephew is shown by the fact that Rustenschacher left the store on several occasions and went into the office, apparently to avoid having to take part in the painful argument. I myself was afraid that I would have to intervene in the argument at any moment, then Karrer raised his walking stick again, banged it on the counter, and said, to all appearances we are dealing with a state of exhaustion, it is possible that we are dealing with a state of exhaustion, but I cannot be bothered at all with such a state of exhaustion, cannot be bothered at all, he said to himself, while he was banging on the counter with his walking stick, in the particular rhythm with which he always banged on the counter in Rustenschacher’s store, apparently to calm his inner state of excitement, Oehler told Scherrer, and then he, Karrer, began once more to heap his excesses of assertion and insinuation concerning the trousers on the head of the salesman. Rustenschacher certainly heard everything from the back of the store, as Oehler told Scherrer, even if it appeared as though Rustenschacher observed nothing happening between Karrer and his nephew, Rustenschacher’s self-control, I told Scherrer, said Oehler, was at an absolute peak, as the argument between Karrer and Rustenschacher’s nephew heated up, Rustenschacher had to exercise a degree of self-control that would have been impossible in another human being. But the way in which Karrer had behaved at certain times in Rustenschacher’s store and because Rustenschacher knew how Karrer always acts in this almost unbearable manner in Rustenschacher’s store and Rustenschacher knew how Karrer always re acts to everything, but he knew that he had nevertheless always calmed down in the end, in fact, whenever we had gone into Rustenschacher’s store, Rustenschacher had always shown a much greater ability to judge Karrer’s state of mind than Scherrer. Suddenly Karrer said to Rustenschacher, Oehler told Scherrer, if you, Rustenschacher, take up a position behind the pair of trousers that your nephew is at this moment holding up to the light for me, immediately behind this pair of trousers that your nephew is holding up to the light for me, I can see your face through this pair of trousers with a clarity with which I do not wish to see your face. But Rustenschacher controlled himself. Whereupon Karrer said, enough trousers! enough materials! enough! Oehler told Scherrer. Immediately after this, however, Oehler told Scherrer, Karrer repeated that with regard to the materials that were lying on the counter they were dealing one hundred percent with Czechoslovakian rejects. Aside from the workmanship, says Karrer, Oehler told Scherrer, as far as these materials were concerned, it was quite obviously a question, even to the layman, of Czechoslovakian rejects. The workmanship is the best, of course, the workmanship is the best, Karrer keeps repeating, that has always been apparent in all the years that I have been coming to Rustenschacher’s store. And how long had he been coming to Rustenschacher’s store? and how many pairs of trousers had he already bought in Rustenschacher’s store? says Karrer, Oehler tells Scherrer, not one button has come off, says Karrer, Oehler told Scherrer. Not a single seam has come undone! says Karrer to Rustenschacher. My sister, says Karrer, has never yet had to sew on a button that has come off, says Karrer, it is true that my sister has never yet had to sew on a single button that has come off a pair of trousers I bought from you, Rustenschacher, because all the buttons that have been sewn onto the trousers I bought from you are really sewn on so securely that no one can tear one of these buttons off. And not a single seam has come undone in all these years in any of the pairs of trousers I have bought in your store! Scherrer noted what I was saying in the so-called shorthand that is customary among psychiatric doctors. And I felt terrible to be sitting here in Pavilion VI in front of Scherrer and making these statements about Karrer, while Karrer is confined in Pavilion VII, we say confined because we don’t want to say locked up or locked up like an animal , says Oehler. Here I am sitting in Pavilion VI and talking about Karrer in Pavilion VII without Karrer’s knowing anything about the fact that I am sitting in Pavilion VI and talking about him in Pavilion VII. And, of course, I did not visit Karrer, when I went into Steinhof, nor when I came away from Steinhof, says Oehler. But Karrer probably couldn’t have been visited. Visiting patients confined in Pavilion VII is not permitted, says Oehler. No one in Pavilion VII is allowed to have visitors. Suddenly Rustenschacher says, I tell Scherrer, says Oehler, that Karrer can try to tear a button off the trousers that are lying on the counter. Or try to rip open one of these seams! says Rustenschacher to Karrer, subject all of these pairs of trousers to a thorough examination, says Rustenschacher, and Rustenschacher invites Karrer to tear, to pull, and to tug at all the pairs of trousers lying on the counter in any way he likes, Oehler told Scherrer. Rustenschacher invited Karrer to do whatever he liked to the trousers. Possibly, Rustenschacher was thinking pedagogically at that moment, Oehler said to Scherrer. Then Oehler said to Rustenschacher that he, Karrer, would refrain when so directly invited to tear up all these pairs of Rustenschacher’s trousers, Oehler told Scherrer. I prefer not to make such a tear test, said Karrer to Rustenschacher, Oehler told Scherrer. For if I did make the attempt, said Karrer, to rip open a seam or even tear a button off just one pair of these trousers, people would at once say that I was mad, and I am on my guard against this, because you should be on your guard against being called mad, Oehler told Scherrer. But if I really were to tear these trousers, Karrer said to Rustenschacher and his nephew, I would tear all of these trousers into rags in the shortest possible time, to say nothing of the fact that I would tear all the buttons off all of these trousers. Such rashness to invite me to tear up all these trousers! says Karrer. Such rashness! Oehler told Scherrer. Then Karrer returned to the thin spots, Oehler told Scherrer, saying that it was remarkable that if you held all of these trousers up to the light, thin spots were to be seen, thin spots that were quite typical of reject materials, says Karrer. Whereupon Rustenschacher’s nephew says, one should not, as anyone knows, hold up a pair of trousers to the light, because all trousers if held up to the light show thin spots. Show me one pair of trousers in the world that you can hold up to the light, says Rustenschacher to Karrer from the back. Not even the newest, not even the newest, says Rustenschacher, Oehler told Scherrer. In every case you would find at least one thin spot in a pair of trousers held up to the light, says Rustenschacher’s nephew, says Oehler to Scherrer. Suddenly Rustenschacher adds from the back: every piece of woven goods reveals a thin spot when held up to the light, a thin spot. To which Karrer replies that every intelligent shopper naturally holds an article that he has chosen to buy up to the light if he doesn’t want to be swindled, Oehler told Scherrer. Every article, no matter what, must be held up to the light if you want to buy it, Karrer said. Even if merchants fear nothing so much as having their articles held up to the light, said Karrer, Oehler told Scherrer. But naturally there are trouser materials and thus trousers, I tell Scherrer, that you can hold up to the light without further ado if you are really dealing with excellent materials, I say, you can hold them up to the light without further ado. But apparently, I tell Scherrer, according to Oehler, we were dealing with English materials in the case of the materials in question and not, as Karrer thought, with Czechoslovakian, and hence not with Czechoslovakian rejects, but I do not believe that we were dealing with excellent, or indeed most excellent English materials, I tell Scherrer, for I saw the thin spots myself in all of these trousers, except that naturally I would not have held forth in the way that Karrer held forth about those thin spots in all the trousers, I tell Scherrer. Probably I would not have gone into Rustenschacher’s store at all, seeing that we had been in Rustenschacher’s store two or three days before the visit to Rustenschacher’s store. It was the same the time before last when we went in: Karrer had Rustenschacher’s nephew hold the trousers up to the light, but not so many pairs of trousers, after just a short time Karrer says, thank you, I’m not going to buy any trousers, and to me, let’s go, and we leave Rustenschacher’s store. But now the situation was totally different. Karrer was already in a state of excitement when he entered Rustenschacher’s store because we had been talking about Hollensteiner the whole way from Klosterneuburgerstrasse to Albersbachstrasse, Karrer had become more and more excited as we made our way, and at the peak of his excitement, I had never seen Karrer so excited before, we went into Rustenschacher’s store. Of course we should not have gone into Rustenschacher’s store in such a high state of excitement, I tell Scherrer. It would have been better not to go into Rustenschacher’s store but to go back to Klosterneuburgerstrasse, but Karrer did not take up my suggestion of returning to Klosterneuburgerstrasse. I have made up my mind to go into Rustenschacher’s store, Karrer says to me, Oehler told Scherrer, and as Karrer’s tone of voice had the character of an irreversible command, I tell Scherrer, says Oehler, I had no choice but to go into Rustenschacher’s store with Karrer on this occasion. And I could never have let Karrer go into Rustenschacher’s store on his own, says Oehler, not in that state. It was clear to me that we were taking a risk in going into Rustenschacher’s store, I tell Scherrer, Karrer’s state prevented me from saying a word against his intention of going into Rustenschacher’s store. If you know Karrer’s nature, I tell Scherrer, says Oehler, you know that if Karrer says he is going into Rustenschacher’s store it is pointless trying to do anything about it. No matter what Karrer’s intention was, when he was in such a condition there was no way of stopping him, no way of persuading him to do otherwise. On the one hand, it was Rustenschacher who let him go into Rustenschacher’s store, on the other hand Rustenschacher’s nephew, both of them were basically repugnant to him, just as, basically, everyone was repugnant to him, even I was repugnant to him: you have to know that everyone was repugnant to him, even those with whom he consorted of his own volition, if you consorted with him of his own volition, you were not exempted from the fact that everybody was repugnant to Karrer, I tell Scherrer, says Oehler. There is no one with such great sensitivity. No one with such fluctuations of consciousness. No one so easily irritated and so ready to be hurt, I tell Scherrer, says Oehler. The truth is Karrer felt he was constantly being watched, and he always reacted as if he felt he was constantly being watched, and for this reason he never had a single moment’s peace. This constant restlessness is also what distinguishes him from everyone else, if constant restlessness can distinguish a person, I tell Scherrer, Oehler says. And to be with a constantly restless person who imagines that he is restless even when he is in reality not restless is the most difficult thing, I tell Scherrer, says Oehler. Even when nothing suggested one or more causes of restlessness, when nothing suggested the least restlessness, Karrer was restless because he had the feeling (the sense) that he was restless, because he had reason to, as he thought. The theory according to which a person is everything he imagines himself to be could be studied in Karrer, the way he always imagined, and he probably imagined this all his life, that he was critically ill without knowing what the illness was that made him critically ill, and probably because of this, and certainly according to the theory, I tell Scherrer, says Oehler, he really was critically ill. When we imagine ourselves to be in a state of mind , no matter what, we are in that state of mind, and thus in that state of illness which we imagine ourselves to be in, in every state that we imagine ourselves in . And we do not allow ourselves to be disturbed in what we imagine, I tell Scherrer, and thus we do not allow what we have imagined to be negated by anything, especially by anything external . What incredible self-confidence, on the one hand, and what incredible weakness of character and helplessness, on the other, psychiatric doctors show, I think, while I am sitting opposite Scherrer and making these statements about Karrer and, in particular, about Karrer’s behavior in Rustenschacher’s store, says Oehler. After a short time I ask myself why I am sitting opposite Scherrer and making these statements and giving this information about Karrer. But I do not spend long thinking about this question, so as not to give Scherrer an opportunity of starting to have thoughts about my unusual behavior towards him, because I had declared myself ready to tell him as much as possible about Karrer that afternoon. I now think it would have been better to get up and leave, without bothering about what Scherrer is thinking, if I were to leave in spite of my assurance that I would talk about Karrer for an hour or two I thought, Oehler says. If only I could go outside, I said to myself while I was sitting opposite Scherrer, out of this terrible whitewashed and barred room, and go away. Go away as far as possible. But, like everyone who sits facing a psychiatric doctor, I had only the one thought, that of not arousing any sort of suspicion in the person sitting opposite me about my own mental condition and that means about my soundness of mind. I thought that basically I was acting against Karrer by going to Scherrer, says Oehler. My conscience was suddenly not clear , do you know what it means to have a sudden feeling that your conscience is not clear with respect to a friend? and it makes things all the worse if your friend is in Karrer’s position, I thought. To speak merely of a bad conscience would be to water the feeling down quite inadmissibly, says Oehler, I was ashamed. For there was no doubt in my mind that Scherrer was an enemy of Karrer’s, but I only became aware of this after a long time, after long observation of Scherrer — whom I have known for years, ever since Karrer was first in Steinhof — and it was only because we were acquainted that I agreed to pay a call on him, but he was not so well known to me that I could say this is someone I know, in that case I would not have accepted Scherrer’s invitation to go to Steinhof and make a statement about Karrer. I thought several times about getting up and leaving, says Oehler, but then I stopped thinking that way, I said to myself it doesn’t matter . Scherrer makes me uneasy because he is so superficial. If I had originally imagined that I was going to visit a scientific man, in the shape of a scientific doctor, I soon recognized that I was sitting across from a charlatan. Too often we recognize too late that we should not have become involved in something that unexpectedly debases us. On the other hand, I had to assume that Scherrer is performing a useful function for Karrer, says Oehler, but I saw more and more that Scherrer, although he is described as the opposite and although he himself believes in this opposite, is indeed convinced by it, is an enemy of Karrer’s, a doctor in a white coat playing the role of a benefactor. To Scherrer, Karrer is nothing more than an object that he misuses. Nothing more than a victim. Nauseated by Scherrer, I tell him that Karrer says that there really are trousers and trouser materials that can be held up to the light, but these , says Karrer and bursts out into a laughter that is quite uncharacteristic of Karrer, because it is characteristic of Karrer’s madness, you don’t need to hold these trousers up to the light , Karrer says, banging on the counter with his walking stick at the same time, to see that we are dealing with Czechoslovakian rejects . Now for the first time I noticed quite clear signs of madness, I tell Scherrer, whereupon, as I can see, Scherrer immediately makes a note, says Oehler, because I am watching all that Scherrer is noting down, says Oehler, Oehler (in other words, I) is saying at this moment: for the first time quite clear signs of madness ; I observe not only how Scherrer reacts, I also observe what Scherrer makes notes of and how Scherrer makes notes . I am not surprised, says Oehler, that Scherrer underlines my comment for the first time signs of madness . It is merely proof of his incompetence, says Oehler. It occurred to me that Rustenschacher was still labeling trousers in the back, I told Scherrer, and I thought it’s incomprehensible, and thus uncanny, that Rustenschacher should be labeling so many pairs of trousers. Possibly it was a sudden, unbelievable increase in Karrer’s state of excitement that prompted Rustenschacher’s incessant labeling of trousers, for Rustenschacher’s incessant labeling of trousers was gradually irritating even me. I thought that Rustenschacher really never sells as many pairs of trousers as he labels, I suddenly tell Scherrer, but he probably also supplies other smaller businesses in the outlying districts, in the twenty-first, twenty-second, and twenty-third districts, in which you can also buy Rustenschacher’s trousers and thus Rustenschacher also plays the role of a trousers wholesaler for a number of such textile firms in outlying districts. Now, Karrer says, in the case of this pair of trousers that you are now holding right in front of my face instead of holding them up to the light, Oehler tells Scherrer, it is clearly a case of Czechoslovakian rejects. It was simply because Karrer did not insult Rustenschacher’s nephew to his face with this new objection to Rustenschacher’s trousers, Oehler told Scherrer. Karrer had at first prolonged his visit to Rustenschacher’s store because of the pains in his leg, I told Scherrer, says Oehler. Apparently we had walked too far before we entered Rustenschacher’s store, and not only too far but also too quickly while at the same time carrying on a most exhausting conversation about Wittgenstein, I tell Scherrer, says Oehler, I mention the name on purpose, because I knew that Scherrer had never heard the name before, and this was confirmed at once, in the very moment that I said the name Wittgenstein, says Oehler, however, at that point Karrer had probably not been thinking about his painful legs for a long time, but simply for the reason that I could not leave him I was unable to leave Rustenschacher’s store. This is something we often observe in ourselves when we are in a room (any room you care to mention): we seem chained to the room (any room you care to mention) and have to stay there, because we cannot leave it when we are upset . Karrer probably wanted to leave Rustenschacher’s store, I tell Scherrer, says Oehler, but Karrer no longer had the strength to do so. And I myself was no longer capable of taking Karrer out of Rustenschacher’s store at the crucial moment. After Rustenschacher had repeated, as his nephew had before him, that the trouser materials with which we were dealing were excellent, he did not, like his nephew before him, say most excellent, just excellent, materials and that it was senseless to maintain that we were dealing with rejects or even with Czechoslovakian rejects, Karrer once again says that in the case of these trousers they were apparently dealing with Czechoslovakian rejects, and he made as if to take a deep breath, as it seemed unsuccessfully, whereupon he wanted to say something else, I tell Scherrer, says Oehler, but he, Karrer, was out of breath and was unable, because he was out of breath, to say what he apparently wanted to say. These thin spots. These thin spots. These thin spots. These thin spots. These thin spots over and over again. These thin spots. These thin spots. These thin spots , incessantly. These thin spots. These thin spots. These thin spots . Rustenschacher had immediately grasped what was happening and, on my orders, Rustenschacher’s nephew had already ordered everything to be done that had to be done, Oehler tells Scherrer.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Walking: A Novella»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Walking: A Novella» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Walking: A Novella» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.