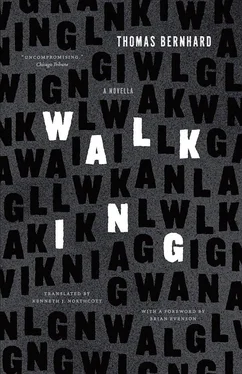

Thomas Bernhard - Walking - A Novella

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Thomas Bernhard - Walking - A Novella» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: University of Chicago Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Walking: A Novella

- Автор:

- Издательство:University of Chicago Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Walking: A Novella: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Walking: A Novella»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

); “a virtuoso of rancor and rage” (

). And although he is favorably compared with Franz Kafka, Samuel Beckett, and Robert Musil, it is only in recent years that he has gained a devoted cult following in America.

A powerful, compact novella,

provides a perfect introduction to the absurd, dark, and uncommonly comic world of Bernhard, showing a preoccupation with themes — illness and madness, isolation, tragic friendships — that would obsess Bernhard throughout his career.

records the conversations of the unnamed narrator and his friend Oehler while they walk, discussing anything that comes to mind but always circling back to their mutual friend Karrer, who has gone irrevocably mad. Perhaps the most overtly philosophical work in Bernhard’s highly philosophical oeuvre,

provides a penetrating meditation on the impossibility of truly thinking.

Walking: A Novella — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Walking: A Novella», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The unbelievable sensitivity of a person like Karrer on the one hand and his great ruthlessness on the other, said Oehler. On the one hand, his overwhelming wealth of feeling and on the other his overwhelming brutality. There is a constant tussle between all the possibilities of human thought and between all the possibilities of a human mind’s sensitivity and between all the possibilities of a human character, says Oehler. On the other hand we are in a state of constant completely natural and not for a moment artificial intellectual preparedness when we are with a person like Karrer. We acquire an increasingly radical and, in fact, an increasingly more radically clear view of and relationship to all objects even if these objects are the sort of objects that in normal circumstances human beings cannot grasp. What until now, until the moment we meet a person like Karrer, we found unattainable we suddenly find attainable and transparent. Suddenly the world no longer consists of layers of darkness but is totally layered in clarity, says Oehler. It is in the recognition of this and in the constant readiness to recognize this, says Oehler, that the difficulties of constantly being with a person like Karrer lie. A person like that is, of course, feared because he is afraid (of being transparent). We are now concerned with a person like Karrer because now he has actually been taken away from us (by being taken into Steinhof). If Karrer were not at this moment in Steinhof and if we did not know for certain that he is in Steinhof, were this not an absolute certainty for us, we would not dare to talk about Karrer, but because Karrer has gone finally mad, as we know, which we know not because science has confirmed it but simply because we only need to use our heads, and what we have ascertained by using our own heads and what, furthermore, science has confirmed for us, for there is no doubt that in Scherrer, says Oehler, we are dealing with a typical representative of science, which Karrer always called so-called science, we do dare to talk about Karrer. Just as Karrer, in general, says Oehler, called everything so-called, there was nothing that he did not call only so-called, nothing that he would not have called so-called, and by so doing his powers achieved an unbelievable force. He, Karrer, had never said, says Oehler, even if on the contrary he did say it frequently and in many cases incessantly, in such incessantly spoken words and in such incessantly used concepts, that it was not a question of science, always only of so-called science, it was not a question of art, only of so-called art, not of technology, only of so-called technology, not of illness, only of so-called illness, not of knowledge, only of so-called knowledge, while saying that everything was only so-called he reached an unbelievable potential and an unparalleled credibility. When we are dealing with people we are only dealing with so-called people, just as when we are dealing with facts we are only dealing with so-called facts, just as the whole of matter, since it only emanates from the human mind, is only so-called matter, just as we know that everything emanates from the human mind and from nothing else, if we understand the concept knowledge and accept it as a concept that we understand. This is what we go on thinking of and we constantly substantiate everything on this basis and on no other. That on this basis things, and things in themselves, are only so-called or, to be completely accurate, only so-called so-called, to use Karrer’s words, says Oehler, goes without saying. The structure of the whole is, as we know, a completely simple one and if we always accept this completely simple structure as our starting point we shall make progress. If we do not accept this completely simple structure of the whole as our starting point, we have what we call a complete standstill, but also a whole as a so-called whole . How could I dare, said Karrer, not to call something only so-called and so draw up an account and design a world, no matter how big and no matter how sensible or how foolish, if I were always only to say to myself (and to act accordingly) that we are dealing with what is so-called and then, over and over again, a so-called so-called something. Just as behavior in its repetition as in its absoluteness is only so-called behavior, Karrer said, says Oehler. Just as we have only a so-called position to adopt vis-à-vis everything we understand and vis-à-vis everything we do not understand, but which we think is real and thus true. Walking with Karrer was an unbroken series of thought processes, says Oehler, which we often developed in juxtaposition one to the other and would then suddenly unjoin them somewhere along the way, when we had reached a place for standing or a place for thinking , but generally at one particular place for standing and thinking when it was a question, says Oehler, of making one of my thoughts into a single one, with another one (his) not into a double one, for a double thought is, as we know, impossible and therefore nonsense. There is never anything but one single thought, just as it is wrong to say that there is a thought beside this thought and what, in such a constellation, is often called a secondary thought, which is sheer nonsense. If Karrer had a thought, and I myself had a thought, and it must be said that we were constantly finding ourselves in that state because it had long since ceased to be possible for us to be in any state but that state, we both constantly had a thought, or, as Karrer would have said, even if he didn’t say it, a so-called constant thought right up to the moment when we dared to make our two separate thoughts into a single one, just as we maintain that about really great thoughts, that is so-called really great thoughts, which are, however, not thoughts, for a so-called really great thought is never a thought, it is a summation of all thoughts pertaining to a so-called great matter, thus there is no such thing as the really great thought, we do not dare, we told ourselves in such a case, says Oehler, when we had been walking together for a long time and had had one thought each individually, but side by side, and when we had held on to this thought and seen through it to make these two completely transparent thoughts into one. That was, one could say, nothing but playfulness, but then you could say that everything is only playfulness, says Oehler, that no matter what we are dealing with we are dealing with playfulness is also a possibility, says Oehler, but I do not contemplate that. The thought is quite right, says Oehler, when we are standing in front of the Obenaus Inn, suddenly stopping in front of the Obenaus, is what Oehler says: the thought that Karrer will never go out to Obenaus again is quite right. Karrer really will not go out to Obenaus again, because he will not come out of Steinhof again. We know that Karrer will not come out of Steinhof again, and thus we know that he will not go into Obenaus again. What will he miss by not going? we immediately ask ourselves, says Oehler, if we get involved with this question, although we know that it is senseless to have asked this question, but if the question has once been asked, let us consider it and approach the response to the question, What will Karrer miss by not going into Obenaus again? It is easy enough to ask the question, but the answer is, however, complicated, for we cannot answer a question like, What will Karrer miss if he does not go into Obenaus again? with a simple yes or a simple no . Although we know that it would have been simpler not to have asked ourselves the question (it doesn’t matter what question), we have nevertheless asked ourselves the (and thus a) question. We have asked ourselves an incredibly complicated question and done so completely consciously, says Oehler, because we think it is possible for us to answer even a complicated question, we are not afraid to answer such a complicated question as What will Karrer miss if he does not go into Obenaus again? Because we think we know so much (and in such depth) about Karrer that we can answer the question, What will Karrer miss if he does not go into Obenaus again? Thus we do not dare to answer the question, we know that we can answer it, we are not risking anything with this question although it is only as we come to the realization that we are risking nothing with this question that we realize that we are risking everything and not only with this question. I would not, however, go so far as to say that I can explain how I answer the question, What will Karrer miss if he does not go into Obenaus again? says Oehler, but I will also not answer the question without explanation and indeed not without explanation of how I have answered the question or of how I came to ask the question at all. If we want to answer a question like the question, What will Karrer miss if he does not go into Obenaus again? we have to answer it ourselves , but this presupposes a complete knowledge of Karrer’s circumstances with relation to Obenaus and thereafter, of course, the full knowledge of everything connected with Karrer and with Obenaus, by which means we arrive at the fact that we cannot answer the question, What will Karrer miss if he does not go into Obenaus again? The assertion that we answer the question while answering it is thus a false one, because we have probably answered the question and, as we believe and know, have answered it ourselves, we haven’t answered it at all, because we have simply not answered the question ourselves, because it is not possible to answer a question like the question, What will Karrer miss if he does not go into Obenaus again? Because we have not asked the question, Will Karrer go into Obenaus again? which could be answered simply by yes or no, in the actual case in point by answering no, and would thus cause ourselves no difficulty, but instead we are asking, What will Karrer miss if he does not go into Obenaus again? it is automatically a question that cannot be answered, says Oehler. Apart from that, we do, however, answer this question when we call the question that we asked ourselves a so-called question and the answer that we give a so-called answer. While we are again acting within the framework of the concept of the so-called and are thus thinking , it seems to us quite possible to answer the question, What will Karrer miss if he does not go into Obenaus again? But the question, What will Karrer miss if he does not go into Obenaus again? can also be applied to me . I can ask, What will I miss if I do not go into Obenaus again? or you can ask yourself, What will I miss if I do not go into Obenaus again? but at the same time it is most highly probable that one of these days I will indeed go into Obenaus again and you will probably go into Obenaus again to eat or drink something, says Oehler. I can say in my opinion Karrer will not go into Obenaus again, I can even say Karrer will probably not go into Obenaus again, I can say with certainty or definitely that Karrer will not go into Obenaus again. But I cannot ask, What will Karrer miss by the fact that he will not go into Obenaus again? because I cannot answer the question. But let’s simply make the attempt to ask ourselves, What does a person who has often been to Obenaus miss if he suddenly does not go into Obenaus any more (and indeed never again)? says Oehler. Suppose such a person simply never goes among the people who are sitting there, says Oehler. When we ask it in this way, we see that we cannot answer the question because in the meantime we have expanded it by an endless number of other questions. If, nevertheless, we do ask, says Oehler, and we start with the people who are sitting in Obenaus. We first ask, What is or who is sitting in Obenaus? so that we can then ask, Whom does someone who suddenly does not go into Obenaus again ( ever again ) miss? Then we at once ask ourselves, With which of the people sitting in Obenaus shall I begin? and so on. Look, says Oehler, we can ask any question we like, we cannot answer the question if we really want to answer it, to this extent there is not a single question in the whole conceptual world that can be answered. But in spite of this, millions and millions of questions are constantly being asked and answered by questions, as we know, and those who ask the questions and those who answer are not bothered by whether it is wrong because they cannot be bothered, so as not to stop, so that there shall suddenly be nothing more, says Oehler. Here, in front of Obenaus, look, here, up there on the fourth floor, I once lived in a room, a very small room, when I came back from America, says Oehler. He’d come back from America and had said to himself, you should take a room in the place where you lived thirty years ago in the ninth district, and he had taken a room in the ninth district in the Obenaus. But suddenly he couldn’t stand it any longer, not in this street any longer, not in this city any longer, says Oehler. During his stay in America, everything had changed in the city in which he was suddenly living again after thirty years in what for him was a horrible way. I hadn’t reckoned on that, says Oehler. I suddenly realized that there was nothing left for me in this city, says Oehler, but now that I had, as it happened, returned to it and, to tell the truth, with the intention of staying forever , I was not able immediately to turn around and go back to America. For I had really left America with the intention of leaving America forever, says Oehler. I realized, on the one hand, that there was nothing left for me in Vienna, says Oehler and, on the other, I realized with all the acuity of my intellect that there was also nothing more left for me in America, and he had walked through the city for days and weeks and months pondering how he would commit suicide. For it was clear to me that I must commit suicide, says Oehler, completely and utterly clear, only not how and also not exactly when , but it was clear to me that it would be soon , because it had to be soon. He went into the inner city again and again, says Oehler, and stood in front of the front doors of the inner city and looked for a particular name from his childhood and his youth, a name that was either loved or feared, but which was known to him, but he did not find a single one of these names. Where have all these people gone who are associated with the names that are familiar to me, but which I cannot find on any of these doors? I asked myself, says Oehler. He kept on asking himself this question for weeks and for months. We often go on asking the same question for months at a time, he says, ask ourselves or ask others but above all we ask ourselves and when, even after the longest time, even after the passage of years, we have still not been able to answer this question because it is not possible for us to answer it, it doesn’t matter what the question is, says Oehler, we ask another, a new, question, but perhaps again a question that we have already asked ourselves, and so it goes on throughout life, until the mind can stand it no longer. Where have all these people, friends, relatives, enemies gone to? he had asked himself and had gone on and on looking for names, even at night this questioning about the names had given him no peace. Were there not hundreds and thousands of names? he had asked himself. Where are all these people with whom I had contact thirty years ago? he asked himself. If only I were to meet just a single one of these people. Where have they gone to? he asked himself incessantly, and why. Suddenly it became clear to him that all the people he was looking for no longer existed. These people no longer exist, he suddenly thought, there’s no sense in looking for these people because they no longer exist, he suddenly said to himself, and he gave up his room in Obenaus and went into the mountains, into the country. I went into the mountains, says Oehler, but I couldn’t stand it in the mountains either and came back into the city again. I have often stood here with Karrer beneath the Obenaus, says Oehler, and talked to him about all these frightful associations. Then we, Oehler and I, were on the Friedensbrücke. Oehler tells me that Karrer’s proposal to explain one of Wittgenstein’s statements to him on the Friedensbrücke came to nothing; because he was so exhausted, Karrer did not even mention Wittgenstein’s name again on the Friedensbrücke. I myself was not capable of mentioning Ferdinand Ebner’s name any more, says Oehler. In recent times we have very often found ourselves in a state of exhaustion in which we were no longer able to explain what we intended to explain. We used the Friedensbrücke to relieve our states of exhaustion, says Oehler. There were two statements we wanted to explain to each other, says Oehler, I wanted to explain to Karrer a statement of Wittgenstein’s that was completely unclear to him, and Karrer wanted to explain a statement by Ferdinand Ebner that was completely unclear to me. But because we were exhausted we were suddenly no longer capable, there on the Friedensbrücke, of saying the names of Wittgenstein and Ferdinand Ebner because we had brought our walking and our thinking, the one out of the other, to an incredible, almost unbearable, state of nervous tension. We had already thought that this practice of bringing walking and thinking to the point of the most terrible nervous tension could not go on for long without causing harm, and in fact we were unable to carry on the practice, says Oehler. Karrer had to put up with the consequences, I myself was so weakened by Karrer’s, I have to say, complete nervous breakdown, for that is how I can unequivocally describe Karrer’s madness, as a fatal structure of the brain, that I can no longer say the word Wittgenstein on the Friedensbrücke, let alone say anything about Wittgenstein or anything connected with Wittgenstein, says Oehler, looking at the traffic on the Friedensbrücke. Whereas we always thought we could make walking and thinking into a single total process , even for a fairly long time, I now have to say that it is impossible to make walking and thinking into one total process for a fairly long period of time. For, in fact, it is not possible to walk and to think with the same intensity for a fairly long period of time , sometimes we walk more intensively, but think less intensively, then we think intensively and do not walk as intensively as we are thinking, sometimes we think with a much higher presence of mind than we walk with and sometimes we walk with a far higher presence of mind than we think with, but we cannot walk and think with the same presence of mind, says Oehler, just as we cannot walk and think with the same intensity over a fairly long period of time and make walking and thinking for a fairly long period of time into a total whole with a total equality of value. If we walk more intensively, our thinking lets up, says Oehler, if we think more intensively, our walking does. On the other hand, we have to walk in order to be able to think, says Oehler, just as we have to think in order to be able to walk, the one derives from the other and the one derives from the other with ever-increasing skill. But never beyond the point of exhaustion. We cannot say we think the way we walk, just as we cannot say we walk the way we think because we cannot walk the way we think, cannot think the way we walk. If we are walking intensively for a long time deep in an intensive thought, says Oehler, then we soon have to stop walking or stop thinking, because it is not possible to walk and to think with the same intensity for a fairly long period of time. Of course, we can say that we succeed in walking evenly and in thinking evenly, but this art is apparently the most difficult and one that we are least able to master. We say of one person he is an excellent thinker and we say of another person he is an excellent walker, but we cannot say of any one person that he is an excellent (or first-rate) thinker and walker at the same time. On the other hand walking and thinking are two completely similar concepts, and we can readily say (and maintain) that the person who walks and thus the person who, for example, walks excellently also thinks excellently, just as the person who thinks, and thus thinks excellently, also walks excellently. If we observe very carefully someone who is walking, we also know how he thinks. If we observe very carefully someone who is thinking, we know how he walks. If we observe most minutely someone walking over a fairly long period of time, we gradually come to know his way of thinking, the structure of his thought, just as we, if we observe someone over a fairly long period of time as to the way he thinks, we will gradually come to know how he walks. So observe, over a fairly long period of time, someone who is thinking and then observe how he walks, or, vice versa, observe someone walking over a fairly long period of time and then observe how he thinks. There is nothing more revealing than to see a thinking person walking, just as there is nothing more revealing than to see a walking person thinking, in the process of which we can easily say that we see how the walker thinks just as we can say that we see how the thinker walks, because we are seeing the thinker walking and conversely seeing the walker thinking, and so on, says Oehler. Walking and thinking are in a perpetual relationship that is based on trust, says Oehler. The science of walking and the science of thinking are basically a single science. How does this person walk and how does he think! we often ask ourselves as though coming to a conclusion, without actually asking ourselves this question as though coming to a conclusion, just as we often ask the question in order to come to a conclusion (without actually asking it), how does this person think, how does this person walk! Whenever I see someone thinking, can I therefore infer from this how he walks? I ask myself, says Oehler, if I see someone walking can I infer how he thinks? No, of course, I may not ask myself this question, for this question is one of those questions that may not be asked because they cannot be asked without being nonsense. But naturally we may not reproach someone who walks, whose walking we have analyzed, for his thinking, before we know his thinking. Just as we may not reproach someone who thinks for his walking before we know his walking. How carelessly this person walks we often think and very often how carelessly this person thinks , and we soon come to realize that this person walks in exactly the same way as he thinks, thinks the same way as he walks. However, we may not ask ourselves how we walk, for then we walk differently from the way we really walk and our walking simply cannot be judged, just as we may not ask ourselves how we think, for then we cannot judge how we think because it is no longer our thinking. Whereas, of course, we can observe someone else without his knowledge (or his being aware of it) and observe how he walks or thinks, that is, his walking and his thinking, we can never observe ourselves without our knowledge (or our being aware of it). If we observe ourselves, we are never observing ourselves but someone else. Thus we can never talk about self-observation, or when we talk about the fact that we observe ourselves we are talking as someone we never are when we are not observing ourselves, and thus when we observe ourselves we are never observing the person we intended to observe but someone else. The concept of self-observation and so, also, of self-description is thus false. Looked at in this light, all concepts (ideas), says Oehler, like self-observation, self-pity, self-accusation and so on, are false. We ourselves do not see ourselves, it is never possible for us to see ourselves. But we also cannot explain to someone else (a different object) what he is like, because we can only tell him how we see him , which probably coincides with what he is but which we cannot explain in such a way as to say this is how he is . Thus everything is something quite different from what it is for us, says Oehler. And always something quite different from what it is for everything else. Quite apart from the fact that even the designations with which we designate things are quite different from the actual ones. To that extent all designations are wrong, says Oehler. But when we entertain such thoughts, he says, we soon see that we are lost in these thoughts. We are lost in every thought if we surrender ourselves to that thought, even if we surrender ourselves to one single thought, we are lost. If I am walking, says Oehler, I am thinking and I maintain that I am walking, and suddenly I think and maintain that I am walking and thinking because that is what I am thinking while I am walking. And when we are walking together and think this thought, we think we are walking together, and suddenly we think, even if we don’t think it together, we are thinking , but it is something different. If I think I am walking, it is something different from your thinking I am walking, just as it is something different if we both think at the same time (or simultaneously) that we are walking, if that is possible. Let’s walk over the Friedensbrücke, I said earlier, says Oehler, and we walked over the Friedensbrücke because I thought I was thinking, I say, I am walking over the Friedensbrücke, I am walking with you so we are walking together over the Friedensbrücke. But it would be quite different were you to have had this thought, let’s go over the Friedensbrücke, if you were to have thought, let’s walk over the Friedensbrücke, and so on. When we are walking, intellectual movement comes with body movement. We always discover when we are walking, and so causing our body to start to move, that our thinking, which was not thinking in our head, also starts to move. We walk with our legs, we say, and think with our head. We could, however, also say we walk with our mind. Imagine walking in such an incredibly unstable state of mind, we think when we see someone walking whom we assume to be in that state of mind, as we think and say. This person is walking completely mindlessly, we say, just as we say, this mindless person is walking incredibly quickly or incredibly slowly or incredibly purposefully. Let’s go, we say, into Franz Josef station when we know that we are going to say, let’s go into Franz Josef station. Or we think we are saying let’s walk over the Friedensbrücke and we walk over the Friedensbrücke because we have anticipated what we are doing, that is, walking over the Friedensbrücke. We think what we have anticipated and do what we have anticipated, says Oehler. After four or five minutes we intended to visit the park in Klosterneuburgerstrasse, the fact that we went into the park in Klosterneuburgerstrasse, says Oehler, presupposed that we knew for four or five minutes that we would go into the park in Klosterneuburgerstrasse. Just as when I say let’s go into Obenaus it means that I have thought, let’s go into Obenaus, irrespective of whether I go into Obenaus or not. But we are lost in thoughts like this, says Oehler, and it is pointless to occupy yourself with thoughts like this for any length of time. Thus we are always on the point of throwing away thoughts, throwing away the thoughts that we have and the thoughts that we always have, because we are in the habit of always having thoughts, throughout our lives, as far as we know, we throw thoughts away, we do nothing else because we are nothing but people who are always tipping out their minds like garbage cans and emptying them wherever they may be. If we have a head full of thoughts we tip our head out like a garbage can, says Oehler, but not everything onto one heap, says Oehler, but always in the place where we happen to be at a given moment. It is for this reason that the world is always full of a stench, because everybody is always emptying out their heads like a garbage can. Unless we find a different method, says Oehler, the world will, without doubt, one day be suffocated by the stench that this thought refuse generates. But it is improbable that there is any other method. All people fill their heads without thinking and without concern for others and they empty them where they like, says Oehler. It is this idea that I find the cruelest of all ideas. The person who thinks also thinks of his thinking as a form of walking, says Oehler. He says my or his or this train of thought. Thus it is absolutely right to say, let’s enter this thought, just as if we were to say, let’s enter this haunted house. Because we say it, says Oehler, because we have this idea, because we, as Karrer would have said, have this so-called idea of such a so-called train of thought. Let’s go further (in thought), we say, when we want to develop a thought further, when we want to progress in a thought. This thought goes too far, and so on, is what is said. If we think that we have to go more quickly (or more slowly) we think that we have to think more quickly, although we know that thinking is not a question of speed, true it does deal with something, which is walking, when it is a question of walking, but thinking has nothing to do with speed, says Oehler. The difference between walking and thinking is that thinking has nothing to do with speed, but walking is actually always involved with speed. Thus, to say let’s walk to Obenaus quickly or let’s walk over the Friedensbrücke quickly is absolutely correct, but to say let’s think faster, let’s think quickly, is wrong, it is nonsense, and so on, says Oehler. When we are walking we are dealing with so-called practical concepts (in Karrer’s words), when we are thinking we are dealing simply with concepts. But we can, of course, says Oehler, make thinking into walking and, vice versa, walking into thinking without departing from the fact that thinking has nothing to do with speed, walking everything. We can also say, over and over again, says Oehler, we have now walked to the end of such and such a road, it doesn’t matter what road, whereas we can never say, now we have thought this thought to an end, there’s no such thing and it is connected with the fact that walking but not thinking is connected with speed. Thinking is by no means speed, walking, quite simply, is speed. But underneath all this, as underneath everything, says Oehler, there is the world (and thus also the thinking) of practical or secondary concepts. We advance through the world of practical concepts or secondary concepts, but not through the world of concepts. In fact, we now intend to visit the park on Klosterneuburgerstrasse; after four or five minutes in the park on Klosterneuburgerstrasse, Oehler suddenly says, we still have some bird food we brought for the birds under the Friedensbrücke in our coat pockets. Do you have the bird food we brought for the birds under the Friedensbrücke in your coat pocket? To which I answer, yes. To our astonishment both of us, Oehler and I, still have, at this moment in the park on Klosterneuburgerstrasse, the bird food in our coat pockets that we brought for the birds under the Friedensbrücke. It is absolutely unusual, says Oehler, for us to forget to feed our bird food to the birds under the Friedensbrücke. Let’s feed the birds our bird food now, says Oehler, and we feed the birds our bird food. We throw our bird food to the birds very quickly and the bird food is eaten up in a short time. These birds have a totally different, much more rapid, way of eating our bird food, says Oehler, different from the birds under the Friedensbrücke. Almost at the same moment, I also say: a totally different way. It was absolutely certain, I think, that I was ready to say the words in a totally different way before Oehler made his statement. We say something, says Oehler, and the other person maintains that he has just thought the same thing and was about to say what we had said. This peculiarity should be an occasion for us to busy ourselves with the peculiarity. But not today. I have never walked from the Friedensbrücke onto Klosterneuburgerstrasse so quickly, says Oehler. We, Karrer and I, also intended, says Oehler, to go straight from the Friedensbrücke back onto Klosterneuburgerstrasse, but no, we went into Rustenschacher’s store, today I really don’t know why we went into Rustenschacher’s store but it’s pointless to think about it. I can still hear myself saying, says Oehler, let’s go back onto Klosterneuburgerstrasse . That is back to where we are now standing, because I always went walking with Karrer here, but certainly not to feed the birds, as I do with you. I can still hear myself saying, let’s go back onto Klosterneuburgerstrasse, we’ll calm down on Klosterneuburgerstrasse . I was already under the impression that what Karrer needed above all else was to calm down, his whole organism was at this moment nothing but sheer unrest: I really did call out to him several times, let’s go onto Klosterneuburgerstrasse , that was what I said, but Karrer wasn’t listening, I asked him to go to Klosterneuburgerstrasse, but Karrer wasn’t listening, he suddenly stopped in front of Rustenschacher’s store, a place I hate, says Oehler, the fact is that I hate Rustenschacher’s store, and said, let’s go into Rustenschacher’s store and we went into Rustenschacher’s store, although it was not, in the least, our intention to go into Rustenschacher’s store, because when we were still in Franz Josef station we had said to one another, today we will neither go to Obenaus nor into Rustenschacher’s store . I can still hear us both stating categorically neither to Obenaus (to drink our beer) nor into Rustenschacher’s store , but suddenly we had gone into Rustenschacher’s store, says Oehler, and what followed you know. What senselessness to reverse a decision, once taken, on the grounds of reason, as we had to say (afterwards) and replace it with what is often a terrible misfortune, says Oehler. I had never known such a hectic pace as when I was walking with Karrer down from the Friedensbrücke in the direction of Klosterneuburgerstrasse and into Rustenschacher’s store, says Oehler. We had never even crossed the square in front of Franz Josef station so quickly. In spite of the people streaming towards us from Franz Josef station, in spite of these people suddenly streaming towards us, in spite of these hundreds of people suddenly streaming towards us, Karrer went towards Franz Josef station, and I thought that we would, as was his custom, sit down on one of the old benches intended for travelers, right in the midst of all the revolting dirt of Franz Josef station, as was his custom, says Oehler, to sit down on one of these benches and watch the people as they jump off the trains and as, in a short while, they start streaming all over the station, but no, shortly before we were going, as I thought, to enter the station and sit down on one of these benches, Karrer turns round and runs to the Friedensbrücke, runs, says Oehler several times, runs, past the “Railroader” clothing store towards the Friedensbrücke and from there into Rustenschacher’s store at an unimaginable speed, says Oehler. Karrer actually ran away from Oehler. Oehler was only able to follow Karrer at a distance of more than ten, for a long while of fifteen or even twenty meters; while he was running along behind Karrer, Oehler kept thinking, if only Karrer doesn’t go into Rustenschacher’s store, if only he won’t be rash enough to go into Rustenschacher’s store, but precisely what Oehler feared, as he was running along behind Karrer, happened. Karrer said, let’s go into Rustenschacher’s store , and Karrer, without waiting for a word from Oehler, who was, by now, exhausted, went straight into Rustenschacher’s store, Karrer tore open the door of Rustenschacher’s store with an incredible vehemence, but was then able to pull himself together, says Oehler, only, of course, to lose control again immediately. Karrer ran to the counter, says Oehler, and the salesman, without arguing, began at once to show Karrer, to whom he had shown all the trousers the week before, all the trousers, to hold up all the trousers to the light. Look, said Karrer, says Oehler, his tone of voice suddenly so quiet, probably because we are now standing still, I have known this street from my childhood and I have been through everything that this street has been through, there is nothing in this street with which I would not be familiar, he, Karrer knew every regularity and every irregularity in this street, and even if it is one of the most ugly, he loved the street like no other. How often have I said to myself, said Karrer, you see these people day in day out, and it is always the same people whom you see and whom you know, always the same faces and always the same head and body movements as they walk, head and body movements that are characteristic of Klosterneuburgerstrasse. You know these hundreds and thousands of people, Karrer said to Oehler, and you know them, even if you do not know them, because basically they are always the same people, all these people are the same and they only differ in the eyes of the superficial observer (as judge). The way they walk and the way they do not walk and the way they shop and do not shop and the way they act in summer and the way they act in winter and the way they are born and the way they die, Karrer said to Oehler. You know all the terrible conditions. You know all the attempts (to live), those who do not emerge from these attempts, this whole attempt at life, this whole state of attempting, seen as a life, Karrer said to Oehler, says Oehler. You went to school here and you survived your father and your mother here, and others will survive you as you survived your father and mother, said Karrer to Oehler. It was on Klosterneuburgerstrasse that all the thoughts that ever occurred to you occurred to you (and if you know the truth, all your ideas, all your rebukes about your environment, your inner world they all occurred to you here). How many monstrosities is Klosterneuburgerstrasse filled with for you? You only need to go onto Klosterneuburgerstrasse, and all life’s misery and all life’s despair come at you. I think of these walls, these rooms with which, and in which, you grew up, the many illnesses characteristic of Klosterneuburgerstrasse, said Karrer, in Oehler’s words, the dogs and the old people tied to the dogs. The way Karrer made these statements was, in Oehler’s words, not surprising in the wake of Hollensteiner’s suicide. Something hopeless, depressing, had taken hold of Karrer after Hollensteiner’s death, something I had never observed in him before. Suddenly, everything took on the somber color of the person who sees nothing but dying and for whom nothing else seems to happen any more but only the dying that surrounds him. But Scherrer, according to Oehler, was not interested in all the changes in Karrer’s personality that were connected with Hollensteiner’s suicide. Do you remember how they dragged you into the entryway of these houses and how they boxed your ears in those entryways, Karrer suddenly says to me in a tone that absolutely shattered me. As if Hollensteiner’s death had darkened the whole human or rather inhuman scene for him. How they beat up your mother and how they beat up your father, says Karrer, says Oehler. These hundreds and thousands of windows shut tight both summer and winter, says Karrer, according to Oehler, and he says it as hopelessly as possible. I shall never forget the days before the visit to Rustenschacher’s store, says Oehler, how Karrer’s condition got worse daily, how everything you had thought was already totally gloomy became gloomier and gloomier. The shouting and the collapsing and the silence on Klosterneuburgerstrasse that followed this shouting and collapsing, said Karrer, says Oehler. And this terrible filth! he says, as though there had never been anything in the world for him but filth. It was precisely the fact that everything on Klosterneuburgerstrasse, that everything remained as it always had been and that you had to fear, if you thought about it, that it would always remain the same and that had gradually made Klosterneuburgerstrasse into an enormous and insoluble problem for him. Waking up and going to sleep on Klosterneuburgerstrasse , Karrer kept repeating. This incessant walking back and forth on Klosterneuburgerstrasse. My own helplessness and immobility on Klosterneuburgerstrasse. In the last two days these statements and scraps of statements had continually repeated themselves, says Oehler. We have absolutely no ability to leave Klosterneuburgerstrasse. We have no power to make decisions any more. What we are doing is nothing. What we breathe is nothing. When we walk, we walk from one hopelessness to another. We walk and we always walk into a still more hopeless hopelessness. Walking away, nothing but walking away , says Karrer, according to Oehler, over and over again. Nothing but walking away. All those years I thought I would alter something, and that means everything, and walk away from Klosterneuburgerstrasse, but nothing changed (because he changed nothing), says Oehler, and he did not go away. If you do not walk away early enough , said Karrer, it is suddenly too late and you can no longer walk away. It is suddenly clear you can do what you like, but you can no longer walk away. No longer being able to alter this problem of not being able to walk away any more occupies your whole life , Karrer is supposed to have said, and from then on that is all that occupies your life. You then grow more and more helpless and weaker and weaker and all you keep saying to yourself is that you should have walked away early enough, and you ask yourself why you did not walk away early enough. But when we ask ourselves why we did not walk away and why we did not walk away early enough, which means did not walk away at the moment when it was high time to do so, we understand nothing more, said Karrer to Oehler. Oehler says: because we did not think intensively enough about changing things when we really should have thought intensively about making changes and in fact did think intensively about making changes, but not intensively enough because we did not think intensively in the most inhuman way about making changes in something, and that means, above all, ourselves, making changes in ourselves to change ourselves and by this means to change everything, said Karrer. The circumstances were always such as to make it impossible for us. Circumstances are everything, we are nothing, said Karrer. What sort of states and what sort of circumstances have I been in, in which I simply have not been able to change myself in all these years because it all boiled down to a question of states and circumstances that could not be changed, said Karrer. Thirty years ago, when you, Oehler, went off to America, where, as I know, most circumstances were really dreadful, Karrer is supposed to have said, I should have left Klosterneuburgerstrasse, but I did not leave it; now I feel this whole humiliation as a truly horrible punishment. Our whole life is composed of nothing but terrible and, at the same time, terrifying circumstances (as states), and if you take life apart it simply disintegrates into frightful circumstances and states, Karrer said to Oehler. And when you are on a street like this for so long a time, so long that you have left the discovery that you have grown old behind you long ago, you can, of course, no longer walk away, in thought yes, but in reality no, but to walk away in thought and not in reality means a double torment, said Karrer, after you are forty, your willpower itself is already so weakened that it is senseless even to attempt to walk away. A street like Klosterneuburgerstrasse is, for a person of my age, a sealed tomb from which you hear nothing but dreadful things, said Karrer. Karrer is supposed to have said the words the vicious process of dying several times, and several times early ruin . How I hated these houses, Karrer is supposed to have said, and yet I kept on going into these houses with a lifelong appetite that is nothing short of depressing. All these hundreds and thousands of mentally sick people who have come out of these houses dead over the course of those years, said Karrer. For every dreadful person who has died from one of these houses, two or three new dreadful people are created into these houses, Karrer is supposed to have said to Oehler. I haven’t been into Rustenschacher’s store for weeks, Karrer said the day before he went into Rustenschacher’s store, says Oehler. We live in a time when one should be at least twenty or thirty years younger if one is to survive, Karrer said to Oehler. There has never been an artificiality like it, an artificiality with such a naturalness, for which one should not be over forty. No matter where you look, you are looking into artificiality, said Karrer. Two or three years ago, this street was still not so artificial that it terrified me. But I cannot explain this artificiality, said Karrer. Just as I cannot explain anything any more, said Karrer. Filth and age and absolute artificiality, said Karrer. You with your Ferdinand Ebner, Karrer kept on repeating, and I, at first, with my Wittgenstein, then you with your Wittgenstein and I with my Ferdinand Ebner. When in addition one is dependent upon a female person, my sister, said Karrer. But it is frightful after years of absence, suddenly to face all these people (in Obenaus), said Karrer. If things are peaceful around me, then I am restless, the more restless I grow, the more peaceful things are around me, and vice versa, said Karrer. When you are suddenly dragged back into your filth, said Karrer. Into the filth that has doubtless increased in the thirty years, said Karrer. After thirty years it is a much filthier filth than it was thirty years ago, says Karrer. When I am lying in bed, assuming that my sister keeps quiet, that she is not pacing up and down in her room, which is opposite mine, said Karrer, that she is not, as she is in the habit of doing just as I have gone to bed, opening up all the cupboards and all the chests and suddenly clearing out all these cupboards and chests, then I think back on what I was thinking the day before, said Karrer. I close my eyes and lay the palms of my hands on the blanket and go back very intensely over the previous day. With a constantly increasing intensity, with an intensity that can constantly be increased. The intensity can always be increased, it may be that this exercise will one day cross the border into madness, but I cannot be bothered about that, said Karrer. The time when I did bother about it is past, I do not bother about it any more, said Karrer. The state of complete indifference, in which I then find myself, said Karrer, is, through and through, a philosophical state.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Walking: A Novella»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Walking: A Novella» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Walking: A Novella» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.