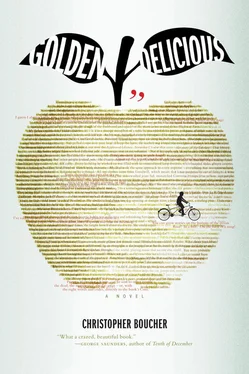

Gus & Paul’s was humming with activity — it seemed like all of Appleseed was there. We stood in line for twenty minutes before finally stepping up to the glass case. “A dozen water rolls,” my Dad said to the fluffy hat behind the counter, “and whatever these guys want.”

The fluffy hat moved over to the glass case.

“Cider Creme, please,” Briana said.

“  ?” said my Dad.

?” said my Dad.

Everything looked so delicious. “I’ll take one of those,” I said, “and one of those, and one of those.”

“One thing only, Fatty,” my sister said, nudging me.

I looked to my Dad. “Can I get two?” I said.

It wasn’t until years later that I put apple and seed together: that I realized how meaningless we were. I didn’t know, for example, that my Dad skipped lunch all those years; that he had to beg his own truck to get him to work sometimes; that he’d borrowed meaning, by that point, from everyone he knew.

“Whatever he wants,” my Dad told the hat, and I pointed to pastry after pastry. The hat collected them in a brown box, tied them with a small white string, and handed the box over the counter. I reached up for the box and took it.

Sentence was my friend, probably my only true friend through the mothering, the forging — most of my high school years, really. Everyone has their pet expressions, but Sentence was something more. For a long time, that expression was the only thing that really understood me.

I found Sentence while working with my father at Belmont, one of the two apartment buildings that he owned and managed. He bought them in the early 1980s, during a meaningful time in Appleseed when the town still ran on apples. Led by the Memory of Johnny Appleseed himself, who once lived and groved here, Appleseed’s apple industry thrived; we sold apple pies, apple cider, appleburgers, applefish, apple chicken, apple pad thai, even apple art made from cores and stems. Something like ninety percent of all the apples in Massachusetts were grown in Appleseed, and people came from all over New England in search of meaning in the apple trade.

My father didn’t know the first thing about apples, but he was a skilled handyman, trained by his father — the Rabbit Eater — in the arts of tenancy and the mysteries of landlording. When we first moved to Appleseed, my Dad worked as a caretaker for a local moustache, answering service calls — heating, plumbing, maintenance — for any one of nine apartment buildings in the downtown. Then the moustache went gray and started selling off his property, and my Dad took out a second mortgage on our house to buy the two least meaningful buildings of the lot. It was a risk — they were located in an iffy neighborhood — but my Dad hoped to translate sweat into meaning.

It didn’t turn out that way, though; the buildings were more stubborn and mysterious than he’d bargained for. Drunk plumbing, missing rooms, snoring wires, you name it — tenants called with problems at all hours of the night. Remember that story I told you a few streets back, about driving to The Ear’s house?

Reader: Sure. To get a “stetch” or something.

A steth —a four-meter foundation stethoscope, which we needed to investigate a strange scratching sound coming from the foundation of Woodside. When my Dad put the listener against the rock, though, he frowned and swore. “Christ,” he said. “Something in the soil.”

“What?” I asked.

He put the headphones over my ears. I heard a steady scratching. “What is that?” I said.

My Dad shook his head.

“Termites?”

One of the whatevers burped in my ear.

“Those would be some big fucking termites,” my Dad said.

My Dad prayed to Armin, an exterminator who’d work for meaning under the table, and he tested the soil all around Woodside. After studying the page fibers, Armin declared the problem to be doubts.

“Sorry?” said my Dad, as we stood on the page.

“Doubts,” Armin said.

“Doubts, are you sure?”

Armin nodded. “You know what’s funny? I’ve been getting more and more of these calls.”

My Dad raised an eyebrow. “I have trouble believing that.”

“It’s true,” said Armin.

Armin had to instill the soil with confidence, which cost a shitload. And that was just one of dozens of mysteries and problems that stumped my father. The buildings were just too much for him to manage alone. Soon he started paying his brother Joump to help him with odd jobs. He enlisted me and my sister, too. My father taught me some of the basic hows — insulation, foyer mediation, missing room listening — but like I said, my sister was the one with the real talent. She really immersed herself in it, reading truebooks on wainscoting and ancient plastering techniques, learning special chants for plumbing and lighting and landscaping, mastering all of the old building arts.

Anyway, I’m getting off track — I was telling you about Sentence the sentence. One day when I was about twelve, my Dad and I were patching up some stucco at Belmont when I saw this eager statement reading through the grass. “Hey,” I said to it, but my Dad stood up and imposed over it. “Shoo!” he said.

“Hey, buddy,” I said to the sentence.

“Git!” my Dad yelled. “You git! Git out of here!”

The sentence skimmed off.

“Dad! What the hell?” I said.

“It’s a stray,  ,” my Dad said. “It’s just begging for food.”

,” my Dad said. “It’s just begging for food.”

“I have some seconds for it,” I said.

“Don’t even think about it,” said my Dad. “What have I told you about feeding wild sentences?”

This was in 1987, when stray language was everywhere in Appleseed. I know that’s hard to believe now — now that every word is counted, and counted on, and counted toward — but in those days it wasn’t strange to see verbing on Epstein Street, infinitives running through the deadgroves. Growing up in Appleseed, you were taught how to respond to wild language. If you saw a semicolon, you paused for a second. If you saw a preposition, you let it pass by you — to the left, or to the right, or over your head.

My Dad couldn’t come with me to Belmont the next day — he had to go see Fox, a master welder in the western margin — so I went back to Belmont myself. When I got there, the Memory of Johnny Appleseed was cutting the grass using an old manual mower. My Dad had a gas-powered one in the basement, but the Memory liked this one. For a while, I could hear the swishy blades of the mower as the Memory shoved it forward. Then he finished, put the mower away, and walked off.

I was adding a third coat of stucco, though, when I felt the breath of words on my ankle. I turned and saw the sentence looking up at me.

“Hey there,” I said. I petted the sentence, and it made a sound. I could tell from its words and its eyes that it meant me no harm. Hark, it was only a newborn — just a subject and a verb: “I am.” That was the whole sentence!

I reached into my pocket and found some seconds and minutes — timecrumbs I carried with me just in case I was late or my thoughts wandered. The sentence leaned in and ate right out of my palm. The poor thing was starving! It finished the seconds and sort of stumbled toward me. Suddenly, I was holding the sentence in my arms.

What was I supposed to do — push it away? Abandon it? These words would die out here. Who would feed them and read them if not for me?

I held “I am.” in my arms while I packed up my tools. Then I sat the sentence on the handlebars of my Bicycle Built for Two and started pedaling home. “Hold on tight!” I told the sentence, and it did — it squinted its eyes as the wind ran through its “I” and “a.”

Читать дальше

?” said my Dad.

?” said my Dad.