“Train for what?” I asked her once, and she sort of glared at me.

“I’m just kidding — you know that,” she said.

When my Mom wasn’t working or training, she would read. Sometimes I’d read next to her. We wouldn’t talk — my Mom would smoke, and sometimes I would eat chips — but I guess I thought I could connect to my mother through the books, if that makes any sense.

Anyway, it was usually just the three of us on Sundays. And every trip to the flea market began the same way: my Dad steered the truck past the tables toward a parking spot while my sister scanned the tables for any potential deals. “Aisle— five ,” my sister said one Sunday. “ ’Bout halfway back.”

“The mirror?”

“The bureau.”

“Is that oak?” My Dad said.

“I can’t tell,” my sister said.

Then we’d park the truck in the fields and the two of them would go charging through the grass toward the bureau.

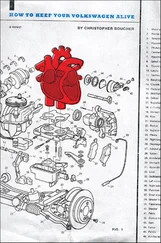

I went off on my own, meanwhile, looking for used books. I’m not talking about the bound brochures they forced you to read in school — the pages that made a sucking sound when you looked at them, that made your eyes sting and your ears echo. I’m talking about true mysteries and war stories like the ones that you could buy for a theory or two or sometimes even find for free at the Appleseed Recycling Center. It’s weird: until I was twelve or so, I couldn’t have cared less about books or reading. One afternoon that winter, though, I found a truebook on a low shelf in our living room. The book was called The Appleseed Strangler . I remember opening it up, seeing all the words trapped there on the page, and feeling an affinity for them. Holding in so many words, I myself sometimes felt like a book — like a cage for sentences.

As I was sprawled out on the living-room floor that day, reading about the Appleseed Strangler, a shadow flashed across the carpet. It was my Mom. “Good story, huh?” she said.

I didn’t say anything.

“Wait until you get to the end — the hanging,” she said.

Two days later my Mom took me to the Appleseed Free Library, where she signed me up for a card and let me check out two books of my choice. Ever since, I’d collected and read as many books as I could find: murder mysteries, histories, histrionics, fallbacks, toronados, you name it.

One day, though, I was sitting next to my Mom at the Library and reading a fallback when I saw a sentence on the page itch itself. “Woah!” I said.

“What?” she hissed.

“That sentence just moved !” I said.

My Mom scorned. She had this one particular scorn that she saved just for me: her whole face squinted, like she was staring into a fierce wind.

“There it goes again!” I said. “It just changed , from—”

“  ,” she hissed. “Be quiet . You’re embarrassing m—”

,” she hissed. “Be quiet . You’re embarrassing m—”

“Now it’s running off the page!”

She grabbed the book from me, closed it, and led me down the red-carpeted stairs and outside. And that was the last time she took me to the Library.

I still continued going to the Library myself, though. When I wasn’t kicking around commas or other dead language out back, I spent almost all of my free time reading in my room in the basement. That basement was dark and cold, and the reading helped me keep warm.

Most of the books in the Library were old, though; for newer trues, the flea bee was a much better bet. All of the local dealers set up tables: Psyches from the Rebel Peddler, Old Gordon from Appleseed Books, Kathy from Sue’s Mysteries, Del from Wilbur’s. They brought bestsellers, overstocks, oddities, you name it. And since I stopped by every week, all of them knew me by name.

Sometimes, though, you found the best fleabooks at the occasionals: a hey who just liked to read; a forget with some swashbidders that they found in the attic and just want to unload. As I was scanning the tables for titles that day, for example, I saw a pig in a van pulling boxes out of his truck. Most of the boxes held tools and old board games, but some of the boxes had books in them. I looked through them, pretending to be only mildly interested. In my skull, though, my thoughts were shouting. “Look — warbooks!” one said. “There’s a self-help!” said another. “And a historical!” said a third.

I held up a book called The Absolutely True Story of the Northampton-Appleseed War . “How much for this one?” I said.

The pig was sweating; he winced as he stood. “Two theories for the hardcovers, one for paperbacks,” he said.

“Take one and a half?”

He thought about it. Then he said, “Sure.”

I tried to keep my thoughts cool as I paid the pig and walked away from the table, but I was thrilled. I loved warbooks — the wars’ personal lives, their political leanings, their dispositions. Wars were mysteries to me, even though I used to see them frequently in Appleseed.

Reader: Wars? In Appleseed?

Sure — you saw them all the time. Most of them were quiet, some so subtle you wouldn’t even know they were there unless you were looking for them. Once, maybe about a year later, I was waiting for my Mom at the hair salon when I noticed a war sitting under one of the hair dryers a few seats over. She was knitting, and when I looked over she smiled politely.

“What are you knitting?” I said.

“A graveyard,” said the war.

Then my Mom stood up from the hairdresser’s chair, studied her buzz cut in the mirror, and told me we were leaving.

I found my sister and father on the other side of the flea — they were carrying the heavy bureau toward the truck. “What’d you find,  ?” said my Dad.

?” said my Dad.

I held up my book.

“Grab a corner, will you?” my sister asked.

I put my book under my arm and took a corner of the bureau. Trying to fit in, I said, “Is this oak?”

“Duh,” said my sister.

“Bri,” said my Dad. “Be nice. It is oak,  .”

.”

We moved the bureau onto the bed of the truck; then we got in the cab and drove toward the exit. It was later now, seven a.m. or so, and more people were arriving. By now, my Dad would say, all the deals were gone — everything meaningful had already been bought or traded.

My Dad steered the truck onto the dirt road. “Gus and Paul’s?” he said.

“Or Bagel Beagle,” I said.

“Gus and Paul’s,” my sister said.

“OK,  ?” said my Dad.

?” said my Dad.

“Sure,” I said.

We drove through West Appleseed and five pages east to Gus & Paul’s, the best bakery in town. As we bumped along the city streets, I leaned my head against the cold window and read the first pages of my truebook.

The hallowed mystery of the Northampton-Appleseed War still bellows in the pause of night. While the war itself was originally believed to have died in truce in 1965, most now believe that to be a hoax. Some say the war moved to Shelburne Falls and died there, under an assumed name, in 1979. Others say the war still lives down in the Quabbin or high on Appleseed Mountain. This book offers no speculations as to the war’s current whereabouts. Rather, The Absolutely True Story of the Northampton-Appleseed War chronicles the facts: when the war began, why, where he was last seen, what those who knew him say about his personality, his love life, and his groundbreaking philosophies — his unique way of looking at the world.

Читать дальше

,” she hissed. “Be quiet . You’re embarrassing m—”

,” she hissed. “Be quiet . You’re embarrassing m—”