I raced into the yard and dropped the bike. The house was swaying in the wind. Its eyes were closed, its face ghost-white, its roof gray and crushed; houseblood ran down the beige siding and onto the sidewalk.

Then I heard a soft rush of air — a gasp, maybe. Was the house still alive?

I heard the thin wind again — it wasn’t yet dead.

I got down on my knees in the wet earth and I said an emergency prayer. I got an automated response: “Welcome to Appleseed. All Emergency Cones are busy right now. If you pray your name, and the time of your prayer—”

I closed the prayer and stood up. The house was still breathing. I ran through my options in my mind. Could I climb the tree, cut the noose?

There was no way. I was too small.

Could the stars help?

No — they weren’t smart enough.

Then I looked up — way up, past the moon. At your Memory.

Memory of the Reader: Who? Me?

Yes. This house is dying. It’s dying!

Memory of the Reader: I can’t — what can I do?

You need to reach down into the page and lift up the house, loosen the tension on that noose.

“I’m just a Memory,” you said.

Just lift up the page — shift the gravity!

“I’m not the Reader,” said the Memory of the Reader. “I can’t lift anything .”

Where is the Reader?

Memory of the Reader: Reading another book.

Another novel ?

Memory of the Reader: Does it matter?

It didn’t — within a few minutes, everything was dead: the house, the words about the house, the noose and the words about the noose. I knelt down on the page and the black houseblood soaked the knees of my white pants.

Shortly after the house took its last breath, Orange Traffic Cones arrived and the hospital followed. The Cones put on crash helmets, climbed ladders, and cut the house down; he landed on the lawn with the terrible sounds of wood splintering and glass smashing. The hospital tried to resuscitate him, but he was dead as a word.

Eventually, the Cones started collecting their tools and talking about where to go for dinner. As I stood in the blood-sopped grass, the hospital approached me wearing a house-sized stethoscope around his neck. The hospital lit a four-foot cigarette and said, “There wasn’t anything I could do,  .”

.”

“I know,” I said.

“You can’t blame yourself.”

“Who else is there to blame?” I said.

The hospital took a drag. “That’s a good question,” he said.

A few minutes later, the Cones’ and hospital’s walkie-talkies started trilling and squawking, and they all left for another call. I stood alone with the dead house, its blood blackening the page. The end.

— Fini ~

Memory of the Reader: Wait.

What.

Memory of the Reader: What happened next? What’s the rest of the story?

That’s the end of it.

Memory of the Reader: But where did you go?

I didn’t go anywhere. It was late. I went inside and fell asleep.

Memory of the Reader: You slept in the corpse of the house?

Sure. What was I supposed to do?

Memory of the Reader: Sleep on the page?

And get carried off by a wild sentence, pulled into another bookwormhole? No, thank you.

Memory of the Reader: I’ve never heard of anyone doing that — sleeping in a deadhouse.

People do it all the time. My father was born in a deadhouse.

Memory of the Reader: What was that like?

Shrug. The rooms had gone gray, the house’s dreams silence and soil. New questions roamed from room to room.

Memory of the Reader: Such as?

Yeah, among others.

For a while I just lay there, listening. Then I prayed to the Memory of Johnny Appleseed and told him I needed help.

With what? he prayed back.

Digging a hole , I prayed.

A hole? he prayed. I should borrow some shovels, then?

Yes , I prayed. The biggest you can find .

That was in 1993, when language in Appleseed berserked, flabbergasted, broke free of its shackles for good. It began mutating, for one thing. All of a sudden — how do I say this? — the language got bigger.

No, not bolder , per se. Literally, bigger.

I think it started when the Daily Core printed a story about wild sentences troughing on the shore of the Kellogg River. That wouldn’t have been news normally, but these sentences were big —six feet high, one source told the Core ; ten, another said. Creepy, right? But hey, odd shit happened all the time in Appleseed. Clouds wore hats. Every so often your shoes died on your feet. Sometimes you were attacked by the glasses on your face. And once or twice a year we felt a great shadow overhead, and looked up into the sky to see a page turning.

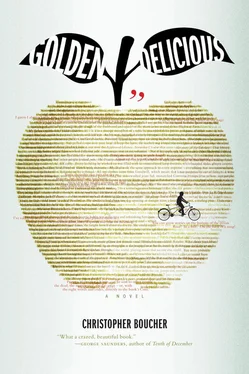

Soon, giant language started appearing everywhere. I was riding the Bicycle Built for Two one day, me on the front seat, Sentence on the backseat, when — plak! I hit— something —and I flew over the handlebars and landed on my side.

“I am.” came crashing down on me. “ ‘My tooth !’ he shouted, painfully,” said Sentence.

I looked at “I am.” There was blood dribbling from his m.

I lumbered back up the road to see what I’d hit. There, in the middle of the street, was a giant black comma. It was about three feet high, and it was—

Was it — snoring?

Yes! It was so fat that it had gotten tired crossing the street — it was taking a nap right there in the road.

“What the—” said “I am.”.

Soon, you could see these gigantic characters everywhere in Appleseed: ten-foot-high exclamation points loitering at the intersection of Colton and Shay; a 7 and a lowercase e ripping Harleys down Grassy Gutter; errant periods frowning all through town, stopping Appleseedians in their tracks.

Not long afterward, phrases and sentences began camouflaging into the page. You’d be right along, just like always, when and . And even though most Appleseedians looked at language as a threat, and no one particularly minded the , it was still odd that . And that, on a warm summer day, there was no at your feet or whimpering outside your window.

We were all miffled. Miffed. Hiffled. We weren’t sure what we could say, or what it meant. What if the meaning changed after we said it? We’d lost control of the story. The Orange Traffic Cones didn’t have any choice, I guess, but to allow the Mothers to increase their monitoring of language. First, they tried restraining the words physically — using parentheses, and when that didn’t work, brackets of various styles — but to no avail.

So the Mothers ordered the Orange Traffic Cones to close the borders: no language was to leave or enter Appleseed. To better regulate our words and their uses, Cones built checkpoints all around town: on Highway Five, at Samsa Avenue, near the worryfields. Everywhere you went you had to wait in line to show a Cone your words. New bans were issued every day: exclamation points were cut, then metaphors, then commands. For a while, periods were banned and every sentence had to end with a question mark. I remember once going to Bagel Beagle during the period ban and trying to order a sandwich. When I placed the order, though, I had to do so in a question: “I’d like a turkey sandwich?”

“Would you?” said the beagle behind the counter.

“On a bagel?” I said.

“Yes?” said the beagle.

“Yes?” I said.

“You would?” said the beagle.

“Yes I said?” I said.

Читать дальше

.”

.”