Two years after my mother left us, my childhood home hanged itself from a tree in the yard of our Appleseed home.

This was in the dark summer. My father had full-blown workhosis by then, and I was spending most of my free time tilling in the deadgroves with the Memory of Johnny Appleseed; he’d recently returned to town, his face and clothes smudged with ink, refusing to discuss where he’d been. The schools were closed; so were most of the stores — there was no fresh food anymore. I ate mostly chips: plain chips for breakfast, salt and vinegar for lunch, barbecue for dinner. Then I’d open a bag of sour cream and onion and fall asleep watching the house’s memories — memories of me, sleeping in the Vox or running around in the backyard; of the rows of parked cars during my sister’s auctions; of my mother watering her plants while smoking a six-foot cigarette; of the four of us, being watched by the television — rerun over and over on the walls of the living room.

Watching those memories, I should have known that 577 was in crisis. Plus, the house leaned dangerously to one side; every wall curved with sorrow. Not to mention the house’s dreams , which I can see now were honest-to-lou night terrors: dreams of falling, of being shot, of being chased through dark tunnels. Once I woke up in the middle of a housedream of being buried alive: the building screamed as the dirt was piled onto the house-sized coffin, blocking the last slivers of light through pine boards.

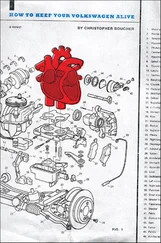

I didn’t just sit by and watch the house suffer, though. I went out to Gilbert’s Bookstore and bought some self-help books: A Room with a View, ReHouse , others. I brought them home and put them on the coffee table.

“What are these?” said the house.

“I really think you should read them,” I said.

“What good are books in a situation like this?”

“These ones have some good ideas,” I said.

“I don’t want good ideas,” said the house. “I just want everything, and everyone, to be quiet.”

A week or two later, I was making a chiplunch when the house asked me if I wanted its collection of old 45s: Gordo and Gordo, The Rabbit, vintage OCDs, The Redirected Flights — some great stuff. “You really don’t want these anymore?” I said.

“I want you to have them,” said 577. “Think of me when you play them.”

I didn’t even own a record player. “OK,” I said.

Right as I started eating my lunch, though, a prayer came in from the Memory of Johnny Appleseed: he’d just traded for some new lightseeds and needed help at the Colton Groves. “I’ll be right there,” I said, and I shoveled some chips into my mouth and ran out the door.

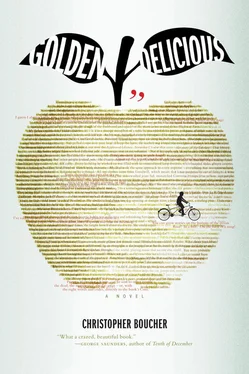

A few minutes later, I was riding over there on my Bicycle Built for Two when I saw the Memory of Johnny Appleseed walking down Inherited Wealth Boulevard. “Where are you going?” I said.

“False alarm,” he said.

“What do you mean?”

“Deadseeds,” he said.

I leaned over the handlebars. “Shit.”

“Got a surprise for you, though,” he said. He held up a soda bottle filled with blue liquid.

“What’s that?” I said.

“Kaddish Cider,” he said.

“Absolutely,” I said.

So we sat in the fields and got kaddished. Cidered out, I lay on my back and looked up at the inside cover. The day-night passed and soon it was dusknight. By then I was sober enough to pick up my bike and ride home.

When I got there, though, the house was gone.

Memory of the Reader: Gone?

It wasn’t there. Which wasn’t so strange on its own — my house, like most houses, took occasional strolls or daytrips. 577 was always sure to tell me where it was going, though, and to return to Converse Street by early evening. But when eight o’clock that night approached, waved, and drove off with no house in sight, I started to worry. I prayed to the house’s friends and family — his mother, his condo brother. His brother didn’t reply; his mother hadn’t seen him.

An hour later, though, I received a prayer from an Or that used to trade with my father. They’d had a falling out over a demo job in Appleseed City — my father said that the Or stole some railroad ties from him — and it would be years more before they coffeed. But the Or prayed that he was down at the Glenwood — a whatif in the downtown — and that my house was sitting right across from him. I rode the Bicycle Built for Two over to the bar. When I walked in, the Or was lounging at the video game table in the front. Or nodded to me. “There’s your domicile,” he said. Then he stood up, gave me a friendly shove, and walked out.

The house was sitting on a stool at the bar. I walked up beside him. “And in walks  ,” said the house.

,” said the house.

I sat down next to him.

“You stink of moon,” he said.

“Why do you think that might be?”

The house shrugged.

“You didn’t tell anyone where you were going.”

“Didn’t want to be found,” said the drunkhouse. “Who told you where I was? The Lamp?”

I shook my head.

“Or?”

“It doesn’t matter,” I said.

“It was Or,” said the house. “That fucking option .”

“You have a job to do,” I said. “You can’t just vanish like that.”

The house belched.

“Nice,” I said.

“Bombs away,” said the house.

“You’re not supposed to be here,” I said. “You’re a home .”

“Home is where the heart is,” said the house.

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“The past is gone ,  ,” said the house. “And it’s not coming back.”

,” said the house. “And it’s not coming back.”

“I’m not talking about the past — I’m talking about right now. I need a place to stay to night .”

“Good for you,” said the house.

“And you,” I said, “have an obligation.”

“Obligation?” said the house. His eyes were watery. “Obligation.”

“Yeah,” I said.

He spun in his stool to face me. “We were a family ,” he said.

What was I supposed to say to that? “I’m going back to Converse Street now. Are you coming or not?”

The house slugged its beer, put on its coat, and walked out with me. I unlocked the Bicycle Built for Two and hopped onto the front seat. The house sat down on the back and we pedaled home.

And I guess I thought that was it — that the house’s runaway had changed something, solved whatever problem it was having. In retrospect, of course, that was naïve of me — especially since the memories and bad dreams persisted.

A few weeks after the house’s return, the Memory of Johnny Appleseed asked me to help him plant some apologies in the deadgroves on Old Mill Road; I worked all day with him and then rode the Bicycle Built for Two back to Converse Street. I was really looking forward to getting home and ripping open a bag of rippled barbecue DeathChips.

When I turned my bike onto our street, though, I saw a strange sight at the tree belt: something was attached to the tree. At first I couldn’t see what — it was dark, and my vision isn’t so good. I figured it was some sort of tree-based installation art. Our trees, like most trees, were very creative, always painting and sculpting, and sometimes they chose to work big, beuysing or serraing.

When I got closer, though, I recognized the shape. It wasn’t art —it was my house, 577, hanging by a noose from a tree in the yard.

“Oh. Oh Core,” said the Bicycle Built for Two.

Читать дальше

,” said the house.

,” said the house.