Thanks, I say after the other kids have started off for home, looking disappointed.

I wouldn't have minded seeing it, really, says Damir.

Edin goes Cuckoo! folds his hands and cracks his knuckles. Vukoje wouldn't have stood a chance against us, he says.

Damir, what are you doing in our town? I ask. I thought you played in Sarajevo now.

Damir laughs. Call me Kiko, he says.

Kiko, is it true what people say about you being able to knock the ball up into the air with your head as often as you like? asks Edin. Aren't they exaggerating?

We could always have a bet on it. . Kiko scratches his forehead, and the bet is one we can't possibly lose. Kiko laughs, the Adam's apple under the skin of his throat jumps up and down, and we shake hands on the deal.

Twelve noon on Sunday. The school yard's empty except for a little girl who is carefully riding around on her bike for the very first time, with her mother holding on to the saddle.

Edin brings the ball with him. We shoot at goal a couple of times.

Do you think he'll come? asks Edin.

Of course he'll come. Got the money?

You know it's summer when the ball bounces and it's so hot that the heat is a space, the leather smacks down on the concrete inside that space and it echoes. If I were a magician who could make things possible, then winter and autumn would be two special days sometime in November, spring would be another word for April, and the rest of the year would be summer, with life echoing, asphalt melting, and Mother putting yogurt on my sunburn.

Here he is. Give me the money.

Hi, boys!

Hi!

Nice and hot, eh?

Yes.

Got the cash?

You don't need to count it, I say, handing Kiko the bundle of notes. He licks his thumb and forefinger and sorts out the crumpled notes in his hand. Gives me his stake. You'd better count it, he says.

All present and correct, I say.

Then let's start.

Just a moment! Edin has a ruler in his hand. He puts it against Kiko's foot and works his way up his leg to his thigh, over his hip and up to his head. He has to stretch a good way for the last bit. The little girl's mother has let go of her, she's screeching and wobbling as she rides the bike, she slows down and falls forward, braking with her feet. The mother claps, the little girl shouts at her: you didn't hold on to me, you let go, she screeches, again, again! she demands.

Edin says: a hundred and ninety-two.

Grown four centimeters since last week, not bad going, grins Kiko, taking off his shirt and throwing up the ball. One, two, counts Edin, three, four, and the heat is a little girl screeching on a bike, five, six, he counts, and late summer is a bet one-hundred- and-ninety-two centimeters high, seven, eight, he counts, and the girl shouts: look, Mama, I'm riding, I'm riding my bike, I can do it! nine, ten, we count, and at ten Kiko begins to whistle, eleven, twelve, he stands there hardly moving, only ducking his head slightly before the ball touches his forehead each time, at thirteen he heads it high into the air, it's unlucky not to do that, he calls, and the ball flies and flies, and Edin says: fourteen, fifteen, sixteen, seventeen, eighteen, nineteen, twenty, twenty-one, twenty-two, twenty-three, twenty-four, twenty-five, twenty-six, twenty-seven, twenty-eight, twenty-nine, thirty, thirty-one, thirty-two, thirty-three, thirty-four, thirty-five, thirty-six, thirty-seven, thirty-eight, thirty-nine, forty, forty-one, forty-two, forty-three, forty-four, forty-five, forty-six, forty-seven, forty-eight, forty-nine, fifty, fifty-one, fifty-two, fifty-three, fifty-four, fifty-five, fifty-six, fifty-seven, fifty-eight, fifty-nine, sixty, sixty-one, sixty-two, sixty-three, sixty-four, sixty-five, sixty-six, sixty-seven, sixty-eight, sixty-nine, seventy, seventy-one, seventy-two, seventy-three, seventy-four, seventy-five, seventy-six, seventy-seven, seventy-eight, seventy-nine, eighty, eighty-one, eighty-two, eighty-three, eighty-four, eighty-five, eighty-six, eighty-seven, eighty-eight, eighty-nine, ninety, ninety-one, ninety-two, ninety-three, ninety-four, ninety-five, ninety-six, ninety-seven, ninety-eight, ninety-nine, a hundred, a hundred and one, a hundred and two, a hundred and three, a hundred and four, a hundred and five, a hundred and six, a hundred and seven, a hundred and eight, a hundred and nine, a hundred and ten, a hundred and eleven, a hundred and twelve, a hundred and thirteen, a hundred and fourteen, a hundred and fifteen, a hundred and sixteen, a hundred and seventeen, a hundred and eighteen, a hundred and nineteen, a hundred and twenty, a hundred and twenty-one, a hundred and twenty-two, a hundred and twenty-three, a hundred and twenty-four, a hundred and twenty-five, a hundred and twenty-six, a hundred and twenty-seven, a hundred and twenty-eight, a hundred and twenty-nine, a hundred and thirty, a hundred and thirty-one, a hundred and thirty-two, a hundred and thirty-three, a hundred and thirty-four, a hundred and thirty-five, a hundred and thirty-six, a hundred and thirty-seven, a hundred and thirty-eight, a hundred and thirty-nine, a hundred and forty, a hundred and forty-one, a hundred and forty-two, a hundred and forty-three, a hundred and forty-four, a hundred and forty-five, a hundred and forty-six, a hundred and forty-seven, a hundred and forty-eight, a hundred and forty-nine, a hundred and fifty, a hundred and fifty-one, a hundred and fifty-two, a hundred and fifty-three, a hundred and fifty-four, a hundred and fifty-five, a hundred and fifty-six, a hundred and fifty-seven, a hundred and fifty-eight, a hundred and fifty-nine, a hundred and sixty, a hundred and sixty-one, a hundred and sixty-two, a hundred and sixty-three, a hundred and sixty-four, a hundred and sixty-five, a hundred and sixty-six, a hundred and sixty-seven, a hundred and sixty-eight, a hundred and sixty-nine, a hundred and seventy, a hundred and seventy-one, a hundred and seventy-two, a hundred and seventy-three, a hundred and seventy-four, a hundred and seventy-five, a hundred and seventy-six, a hundred and seventy-seven, a hundred and seventy-eight, a hundred and seventy-nine, a hundred and eighty, a hundred and eighty-one, a hundred and eighty-two, a hundred and eighty-three, a hundred and eighty-four, a hundred and eighty-five, a hundred and eighty-six, a hundred and eighty-seven, a hundred and eighty-eight, a hundred and eighty-nine, a hundred and ninety, a hundred and ninety-one, a hundred and ninety-two.

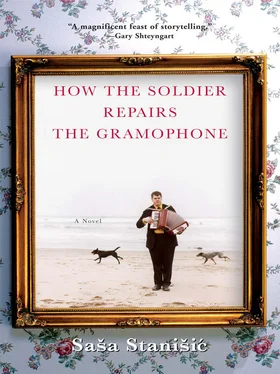

Sas'a Stanis'ic; Why Čika Hasan and Čika Sead are inseparable, and what even those who know most about catfish can't count on

Čika Hasan and Čika Sead don't go fishing for fun, they don't go fishing because they enjoy a struggle against the fish, they don't go fishing because they want peace and quiet, they don't go fishing because you can't have bad thoughts while you're fishing in the Drina. Hasan goes fishing because he wants to catch more fish than Sead, and Sead goes fishing because he wants to catch more fish than Hasan. I'm the one who goes fishing for those other reasons, also because I like fried fish, but all the same I catch more than the two of them put together.

When Hasan first gave blood after his wife's death in an accident, Sead did the same a few days later. And so it went on. Recently Hasan was letting everyone know that he was way ahead of his friend: he'd chalked up one hundred and forty-four pints of blood to Sead's ninety-three.

I stand by the bridge fishing for catfish with leeches. In the early summer heat the path taken by Hasan and Sead on their way from the bridge to me is one long argument. I don't hear exactly what the two of them are arguing about, but judging by their vigorous gestures and the scraps of conversation I catch, the subjects are life, death and cucumber salad. Nice clear water, Aleksandar!

Читать дальше