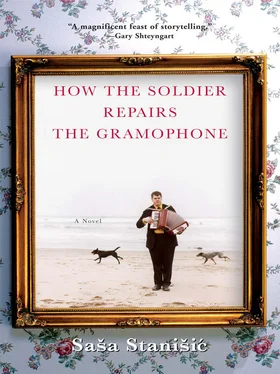

With love from Aleksandar

Hi. Who? Aleksandar! Hey, where areyou calling from? Oh, not bad! Well,lousy, really, how about you?

. . and I hate the water being turned off at midday, and the streetlights not working, and power cuts all the time, and the rubbish not being taken away, and what I hate most of all is the snow. The soldiers burned both mosques down and danced around the ruins, and now there's supposed to be a park there, only it isn't a park, it's a dismal empty space with four benches in it, and I hate everyone who sits on them, and now and then someone comes along with a watering can, but nothing will grow there. You'd say it was a gaping wound and nothing can grow from a wound. Then you'd go invoking some kind of magical nonsense, but you'd need a hell of a powerful magic spell to make things any better here. I hate school, I hate the teachers there, I hate having fifty-four of us in a class, I hate having to stand in line for everything because there's not enough of anything to go around except people and death. I hate my father, I hate his pride and defiance and his principles. For the last six months Milica and I have been trying to persuade him to leave this horrible place, and I hate the way he won't hear of it; I hate it that he's opened a tobacconist's exactly where Bogoljub had his own tobacconist's shop, but what else can he do? Basketball referees are the last thing anyone needs around here, no one plays anything anymore, the gym is crammed full of people, I don't even know if they're prisoners or refugees. I hate the soldiers. I hate the People's Army. I hate the White Eagles. I hate the Green Berets. I hate death. I'm reading, Aleksandar. I like to read. Death is a German champion and a Bosnian outright world champion. I hate the bridge. I hate the shots in the night and the bodies in the river, and I hate the way you don't hear the water when a body hits it, I hate being so far away from everything, from strength and from courage; I hate myself for hiding out up at our old school, and I hate my eyes because they can't see exactly who's being pushed into the deep water and shot there, or maybe even shot while falling. Others are killed up on the bridge, and the women kneel there in the morning, scrubbing the blood away. I hate the man from the dam in Barjina Bašta who complains because they throw so many people into the river all at once that it blocks the outlets. I hate what they're doing to the girls in the hotels — Vilina Vlas and Bikavac — I hate the fire station, I hate the police station, I hate trucks full of girls and women driving to the Vilina Vlas and Bikavac, I hate burning buildings and burning windows with burning people jumping out of them to face the guns, and I hate the way the workers work, the teachers teach, the pigeons fly up in the air, and most of all I hate the snow, the filthy hypocritical snow, because it doesn't cover up anything, anything, anything, but we're so good at covering our eyes it's as if we'd learned nothing else in all those years of neighborliness and fraternity and unity. I hate the way everyone condemns everything, and the way everyone's so good at hating, me too, I hate being good at hating even more than I hate the snow and the new statue of the bronze soldier. I hate myself for not daring to ask the sculptor why the soldier on his monument is carrying a sword and not a bloody knife. And I hate you. I hate you because you've gone, I hate myself because I have to stay here, where even the gypsies don't think it's a good idea to pitch their tents, where dogs form into packs and no one goes swimming in the Drina. You once told me you'd been talking to the Drina. I wonder what tales it would tell now if it could. What would it taste if it had a sense of taste? What does a dead body taste like? Can a river hate too, do you think?

My hatred is endless, Aleksandar. It's there even when I close my eyes.

Dear Asija,

Uncle Miki is alive! He's back home in Višegrad again, he's even living in our old building. For three years no one knew how he was, but then he sent Granny a letter. He was well, he said, he was coming back soon. Granny read the letter aloud to us over the phone. He didn't say where he was coming back from. Granny told us Miki had been seen in Višegrad in '92.

In the Hotel Bikavac? Father raised his voice, thinking of the stories. Heaven forbid!

No one shakes their heads anymore over Granny Katarina and our phone conversations with her. Father once said down the phone: I don't know, I just don't know. He pressed his lips together and pinched the bridge of his nose with his thumb and forefinger. Granny Katarina doesn't live in the present any longer and has made up a past of her own for each of us. I'm paying back the credit that time granted me, she explains. In the Granny version, we're all overtaken by our own past. Six months ago she was diagnosed with astronomically high blood-sugar levels, and the insulin treatment has turned her life into a roller-coaster ride. The days when she sounds worried and thoughtful on the phone are followed by calls to the whole family when she's in tremendous high spirits. Auntie Typhoon thinks we're exaggerating, we take it all much too seriously, after all, she says, it's nice to know what you used to be like. Since Auntie Typhoon had a call of her own from Granny she hasn't said any more on the subject.

There was a party yesterday. Uncle Bora called it “The Dayton Peace Agreement Party” and wrote a speech full of jokes about war, peace, vegetarians and my long hair. I can braid it now. My father said: there's no need to make jokes about Dayton, Dayton itself is the biggest joke ever. A peace agreement giving political accreditation to ethnic cleansing! Father will say almost anything and almost never do anything all his life. We're very alike in that respect, Father and I, only I say rather more than he does, and I do even less.

I imagine there's even more rejoicing over the peace agreement where you are. To be honest: I'm very glad of it, but now I'm afraid of what will happen to us. It looks as if we'll have to go back to Bosnia. But I don't want to go back to the town after everyone was driven out of it. Not wanting to go back is the one point on which my parents and I agree. When they were talking to Uncle Bora and Auntie Typhoon about it, and Mother said: I'd sooner die than look those murderers in the face, Nena Fatima stood up, wrote “Thank you and good-bye” on the low-cut bosom of the woman on the cover of the TV magazine, tore the piece of paper off and stuck it on her forehead.

Nena Fatima only wears her head scarf when it's drizzling out of doors now, but it's always drizzling in Essen. She's made a huge garden in the middle of the inner courtyard. Tomatoes and cucumbers and peppers. The caretaker came to look, and so did the police; they looked at Nena's garden, and we're all expecting to be reported to the authorities. Nena Fatima is the only one in my family that I get on well with. All the neighborhood terriers shit in the garden, and I don't eat lettuce anymore these days.

I was sitting in the garden with Nena when she told me her secret. She reached under her head scarf and put a limp, torn piece of paper down between us. She handed me a comb and turned around. Nena's long hair. I combed it. When I'd finished she stood up and left the note there.

With love, from

Aleksandar

i want to talk again i want to talk

i want to talk i want to talk again but i need a reason it has to be a good reason and that's a fact

i want to see everything

even in the grave i want to go on seeing i'd like to go on seeing even in my sleep

Читать дальше