I remembered what my boss at Foodville had told me about spotting thieves. They’ll never look at you, he said. That’s how you know they’re about to take your shit. When they won’t look at you. So I looked at Arnett and said, “Maybe, now that you mention it.”

“Now that I fucking mention it,” he said.

“I appreciate you hiring me,” I said. “I’ve been needing the work.”

“Really? It’s not because of Jennifer?” He twinkled his fingers around like he was tickling something, then closed them into a fist. “You saying you don’t like looking at her? What’s wrong with her? I take issue with the fact that you don’t fucking like looking at her.”

“Nothing’s wrong with her,” I said.

“So you do like looking at her. That’s what you’re saying. You’re here to eyeball my girl.”

“Ain’t nothing wrong with her. That’s all I’m saying.”

He nodded. “Nope. She’s a tight little piece. You ought to see her upside down,” he said. “Like when she can’t breathe? And her face is about to bust out. Sometimes I want to see her dead, you know? That’s how much I love her. Sometimes while we’re crunching, I’ll tell her, ‘Die, you bitch, just die.’ ” He was making serious progress with the drink and his voice was slurring. His eyes fixed on a point ahead of us, not in the forest beyond or the yard where we sat, but something somewhere in the space between.

“What’s she think about that?” I said.

“She likes it when I tell her to die. It’s not my fault that’s what she wants. You think it’s my fault?”

“No. You really love her.”

“Don’t tell me who I fucking love. She’ll say shit like, ‘Tell me to die again.’ Shit like that. And if I do it long enough, when she’s about to come she’ll say, ‘Oh God, oh my God, I’m dying, I’m dying.’ ”

He took a live shotgun shell from the table, shoved it between two boards supporting the porch roof and pointed at the brass circle gleaming around the nickel hammer button. “Hit the bull’s-eye,” he said, and took a socket wrench and smacked it.

The blast split my ears. Splinters of wood flying.

“I’m dead! I’m dead!” He threw his hands back. The slurpee was at his feet. He picked it up, gulped again and then went around the corner to piss.

The cup stood next to me. I took the bottle out of my pocket, ears still singing and beating, unscrewed the cap, poured the solution into the drink and stirred it around with the straw, then shoved the bottle in my pocket. I’d bury it in the woods later. I walked to the edge of the yard, in case he sniffed the drink, and looked down over the world.

Some other leaf was sailing around out there. But the more I stared at it, the more it looked like a small hole, a little puncture wound in the sky. What if there was an entire world behind the surface of this one? A darker place made of all the things we hide?

He came back, picked up the cup and drained it, hissed like a match getting doused, went up the porch steps and took a seat at the table. “Unadulterated,” he said, pulling out a pack of cigarettes. “Smooth morning time.” He ran his fingers through his hair and tossed his head a few times like he had water in his ears. “Over there,” he said. “The fuck is that?”

It was the sound of an engine. “I’ll check it out,” I told him.

The noise of tires on shale rose from the bottom of the hollow. Jennifer’s truck was moving up the access road, trailing a dust cloud.

He leaned back in the chair. “Think I need to lie down.”

“Somebody’s coming,” I said.

“Oh yeah? What other secrets you want to let me in on?”

Arnett looked like he’d become very heavy. He got out of the chair and lay on his back on the boards. The truck was making steady progress. With her shades on, Jennifer sat in the cab clutching the wheel, and it looked like she was grooving. Arnett lay next to the plates of possum bones, his hand across his middle as it rose and fell.

—

The grass out back between the inn and the barn was knee high. It sounded like a breath in the breeze. The worn boards of the barn had collapsed into some kind of fencing, and that’s where the pigs and dogs were waiting. Two bungee cords held the gate shut, and they hung back against the fence when I unlatched them. The hogs were squealing and bouncing, the hounds slinking behind them and starting into an open cry when I pushed the gate door, and they raced out, snatching and slavering at one another. I’d heard of pigs eating their own farmers, and they ran away from the barn like they knew what they were supposed to do.

I met the truck partways down and climbed in. “Turn around,” I told her. “ Now .”

“You get it done?”

“I did what you said.”

She drove up to the edge of the lot to turn around. I looked at the porch but couldn’t make out whether Arnett was there or not. “Keep turning,” I said. “Keep going.”

“Let’s just check.” She yanked the emergency brake. “See how capable you really are.”

“He was down the last I saw. There’s nothing else we can do. Let’s please get the fuck away from here.”

She started back down the access and my hands shook as I gripped my knees, from nerves and the road rattling us. She took a longneck from her purse. Trees blended green in the window behind her. She eased the bottle between my legs with fingers around the top of it, but I couldn’t appreciate the sight. “I can’t right now,” I said.

“You better.”

I turned it up to my mouth and it foamed onto my shirt. She was right, it was calming, so I began telling her how it all went down. She stood on the brake and we side-tailed in the gravel. “So he’s alive,” she said. “You fucked up a perfectly easy thing.”

I looked out my window and took another swig.

She got out, came around to open my door and told me to get out. I set the bottle on the floorboard and stepped down just as she swung at me in the road. I jumped back and she went reeling from the miss, tripping and rolling into the ditch. I stood over her. “It might be working,” I said. “He drank the stuff. He did that. We need to get going.”

“We need to stay right here.” She got up and went back to the truck and brought out a handle of bourbon. Some was already gone.

“Don’t point that at me.”

“Let’s get a blanket,” she said. “Go into the woods and hide out. I mean, camp. We don’t got a thing to hide because we didn’t do anything. We didn’t run. Only people who run are the people that did something.” She left the bottle on the bench seat, put a foot on the rear wheel and hopped into the bed.

While she was gathering her stuff, I unscrewed the cap and poured warm whiskey down my throat. It burned my stomach. I took another drink for good luck. What was I worried about? Things had gone perfect. I gave a guy what he asked for. I didn’t have to explain shit to anybody. It was hot out and he drank too much. That same old story.

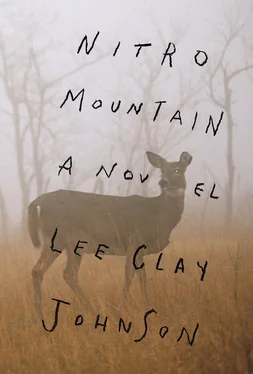

The truck didn’t have a blanket, only a tarp. We hiked it far back in the woods, spread it out and started drinking properly in our nice little nest, all leaves and sticks and plastic. We drank until Nitro Mountain’s light started glowing somewhere behind us.

“It’s getting dark,” I said.

“It already did that,” she said.

I got up and walked over to a tree for a piss and then a puke. “We gotta go.”

“I’m sorry I didn’t think you gave it to him,” she said. She was on her knees and brushing off the tarp, a black square in the thicket. She patted the place beside her. Somehow I made it there and we finished the bottle. “Next what we do is wait and see what happens and keep quiet,” she said. “But enough of that for now. There’s one more thing I need.”

Читать дальше

![Lee Jungmin - Хвала Орку 1-128 [некоммерческий перевод с корейского]](/books/33159/lee-jungmin-hvala-orku-1-thumb.webp)