After, my head in her lap, her finger drawing on my ear, she said, “I seen shit like this in detective movies. The thing that gets you is the cops tracing the killing back to some kind of deal.”

“You ever tell the cops about what he did to you?”

“Never told nobody shit.”

“But people know y’all were together.”

“Are,” she said. “ Are together. You got to do it. Get close to him. Get him in a situation where he sees you as the giving type. You call my phone and I’ll let you talk to him.”

“But he’ll know something’s up if I’m calling your number.”

“I’ll tell him tonight I met somebody looking for work. Ran into you outside the Hairport. When you talk to him, tell him that. And tell him about the trouble you been in. Lost your license. He’ll like that part. Tell him you’re needing work. Make everybody see you as being on his side.”

—

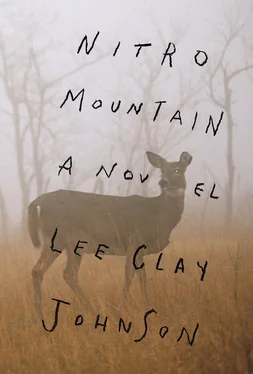

The Lookout was a four-story disaster, twisting clapboard siding and slate shingles sliding off the roof, the whole thing leaning just below the peak of Nitro Mountain. Arnett had set up ladders and scaffolding all over the place. I was using my bad arm to steady myself, climb, hold nails straight, even pull away siding. I spent most of my working hours up around the roof, beneath the sun’s nose. I could look down over my shoulder and see the scab that was Bordon, the infected area around it, and past that the curve of the earth.

Stilted behind me on the last rocky incline was that tower with the red light. I’d grown up gazing at it, wondering what it was, but even now, being so close to it, I still didn’t have much of an idea. Planes never flew near here. Just some souvenir left by the coal company.

The mountain had a different name before Nitro. I’d heard old-timers call it Paran. But that was before coal miners hollowed it out and created air pockets that made the ground unfit to stand on, not to mention all the explosives they’d left behind in those tunnels. By now the county had condemned it.

I’d never been any closer than the highway or had any reason to risk stepping on that forsaken land, but I’d ended up doing exactly what Jennifer said. I called Arnett, explained myself and asked if he’d let me work for him.

“Jennifer told me about you,” he said. “We know each other?”

“Nah.”

“Good. Let’s do a trial run. See if you’re desperate enough.”

My parents’ house was a dozen miles down the road from the Lookout’s front access, and Arnett picked me up in Jennifer’s truck that same day. Bouncing and bottoming out along the dusty trail back up, he said, “There’ll have to be a lot of training before I actually start paying you.”

“That’s all right. I’m a quick study.”

“That’s what she said.”

That night he got too drunk to drive me home and decided to keep me on. Anyway, he needed another worker to make the project look real. According to him, the place had once been his uncle’s and he now believed it ought to be his, but blood rights didn’t mean much in the legal world. He wouldn’t say more than that. We were hanging out in the downstairs bar and he asked if I’d ever been in a strip club, a whorehouse, anywhere. “The bar’s where it all goes down.”

His face was swollen to the point of looking like he’d been stung by some huge insect. He also owned guns. A lot of them. Since moving up here, he’d developed the habit of going killing — not hunting — and then preserving the corpses with homemade embalming fluids, filling the rooms upstairs with them. A few days in, prying away some rotten wood, I peeked into a window and saw busts of bucks, flying geese, a fox forever frozen in the motion of running. Some were mounted on the walls, most just piled on the floor, a few already rotting. The next window gave a view into Arnett and Jennifer’s bedroom, where a hog and a dog hung together by wires in a screeching position above the bed.

It turned into a week of fluorescent green mountains, the sickly scent of pines, vistas so high my stomach turned. I was working up on the ladder one day when a vulture floated past and brushed my ear with its wing. “Hello, my friend,” I said. It glided away, combing the clouds with its feathers. “I knew you’d make it.”

When I looked down, Arnett was watching me. “I bet it’s hard jerking off up there, ain’t it?” he said. “Oh, I’m a very fine person.” He went away for a while and came back carrying a long-barreled shotgun. I tried not to fall off the ladder. “Get down here and follow me,” he said.

We walked behind the barn to the pigpen and I kept my distance. When I caught up, he told me to get on my knees. “Look under there,” he said, pointing at where the wall met the ground. I could see a possum hiding in the washout. It had purple ears and pink fingertips. “Scare it out of there,” he said.

I took a shovel and kind of rolled the thing into the light. It moved like its eyes hurt, probably trying to decide whether to play dead or make a run for it. Arnett pumped the action, pulled the trigger and the little guy’s entire head just went poof into a wet cloud, the blast cracking and echoing down the valley.

I did what he told me, broke some dead branches over my knee, dropped them in a metal trash can lid, sprinkled some gasoline over it and got a fire going. Arnett gutted and skinned the possum. I stretched chicken wire across the lid over the coals. When it was cooked, Arnett divided up the smoking carcass onto two plastic plates and poured vinegar and beer all over his. He pulled a handful of wild onion shoots from the yard and laid them on top. “You know how to start a love letter to a possum?” he said. “Possum, O! possum…”

He dug in like I’d never seen anyone eat before, juice dripping off his chin while he chewed and sucked the meat. He looked like a feral beast that needed to be put down. We kept quiet until there were only bones left. “Feed the rest to the hogs,” he said, handing me his plate. “They’ll eat anything.”

“You really got quite an operation out here,” I said.

“Last-resort desperation. What was I supposed to do? Not move in?”

“Yeah.”

“Yeah move in? Or yeah not move in? I’m asking you.”

“Yeah, it was empty,” I said.

“I put a camera in the toilet bowl. Maybe you’ve heard of me. Toilet Bowl Guy. That’s why I’m up here. Get some peace and fucking quiet. I’m not ashamed. It’s all happening anyways, all that piss and shit. Why can’t I watch? It’s not like it’s not happening if I can’t see it.”

“True.”

“People ought to be open with each other. Share what’s on the inside of ourselves, you know? I’m a caring person. I like to know how a woman feels on the inside.”

“You’re a sensitive guy.”

“Did I ask you to touch me? Don’t touch me, fuck. K?”

“I didn’t.”

“I said, Don’t!”

The noise of wind over my ears. The bending pines. I shut up and listened.

“You know, some motherfucker turned me in. That’s why I’m up here. I’ll figure out who it was. Soon as I finish going through all my footage. The stuff they didn’t get from me. Got weeks of it, man. Months.”

We were sitting around an open cooler watching a few cans of Coors float in the melted ice. I dumped a gym bag of Arnett’s power tools onto the porch and started untangling cords. He told me good luck and got up to go inside. “I’m going to find Jennifer,” he said. “Learn about her interior self.”

I worked for a while longer on the cords, drank some beer and watched the day get hotter. The plates of bones remained on the porch. Eventually a green Jeep Wrangler with mud splashes on the sides rolled into the middle of the lot and parked with its front wheels at a cut. The man driving had some trouble getting out. His shoulders sloped under a gray suit jacket and his head, even when he looked up, seemed bowed. “Howdy,” he said.

Читать дальше

![Lee Jungmin - Хвала Орку 1-128 [некоммерческий перевод с корейского]](/books/33159/lee-jungmin-hvala-orku-1-thumb.webp)