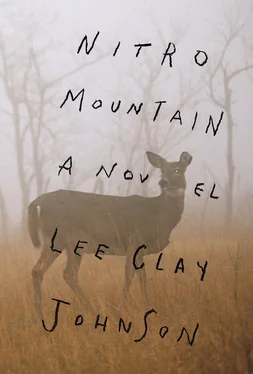

Lee Clay Johnson

Nitro Mountain

We were sitting in my truck in front of the diner she was working at. Greg, her boss, had everybody convinced he was a genius.

“He’s really smart,” Jennifer said. “You know what he told me yesterday while I was in the kitchen?” I rolled down the window and let in cold air. She took face powder from the glove box, bent the rearview at her face and dusted her nose. Headlights came flickering from way behind us. “You don’t even care,” she said.

“I care,” I said. “I’d like to kick his ass.” The headlights were getting closer.

“Yeah, right. Remember when you found that wounded squirrel?”

I turned to see a lifted Tacoma with an aluminum hound cage in the bed rush past. Barks and bays twisted around us and then away as the taillights took the next turn.

“It was a baby. It was lost. It found me.”

“You cried when it died.”

“That was a while ago,” I said.

“You’ve never even been hunting.”

“I fish.”

“Catch and release.”

“I catch and keep, darling,” I said, reaching for her jeans.

She knocked my hand away. Choosing not to hunt around here was tougher than doing it, given all the shit people talked if you weren’t waddling around in orange come deer season. “Don’t mess with Greg anymore,” I said.

“Aw, look, it’s jealous.” She petted my arm.

Hand to chin, I pushed my head sideways, to the point of pain, and held it there until my neck cracked. She wasn’t even going to kiss me. When things got like this between us, I had a habit of hurting myself in front of her. See if she’d say something.

She hummed to herself, checked her watch. “Don’t be here when I get off,” she said.

“How else you gonna get off?” I said.

“We’re done. I’m leaving.”

“Please,” I said. “Don’t.”

She walked to the diner without looking back, smoothed a hand through her hair at the door and made sure she looked good before going in. She did. It was the end of November and the sun was barely cracking the sky. Clouds scattered above the northwest mountains. It got dark so early these days, and it never got all that light.

The town was shadowed by hills. One road this way, one road that way, and their unfortunate intersection was the main square with a brick courthouse that had seen nobler days. The Bordon post office, the library, empty storefronts and a couple shops that hadn’t gone under yet. And then the abandoned Dairy Queen, my sister’s apartment complex and this diner. North of town off 231, toward Nitro Mountain, were the gas station and the Foodville grocery store. Sprawl, if you could even call it that. Then the country opened up. My folks’ place was out there. All the roads and houses seemed to be crushed beneath the foothills, on the verge of burial. West of everything, mountains scraped the sky. At night you could see a red light on top of Nitro Mountain.

South of town was a tiny church with a homeless shelter in the basement. I worked there part-time for cash, morning shifts that involved standing behind a desk only a foot away from so many crises worse than mine, or just running around and handing out towels and soap. It was a strange thing for me to be doing. I always felt closer to the other side of the desk.

On a morning when I’d shown up to help open the shelter after a night of playing bluegrass music and drinking blended whiskey, one of the old bums stepped to the desk to sign in, gazed through my skull, grinned and said, “You look worse than I do today. And I’m a dead man walking.” He looked around. “Somebody do math?”

When things slowed down that day I grabbed a single-size bottle of mouthwash from the dental drawer and jogged upstairs to the employee bathroom. A few sticky blinks. The room rocked. I swished the shot of Scope and before spitting I checked the label for the alcohol percentage. Hard to read. Looked high. Not that bad. I swallowed and it made me feel better, and for that I felt worse.

Since then, I had promised myself never to stay out late before a morning shift. No matter what. Even if I was playing music. Even if the drinks were free. Even if my girlfriend had just left me. And there was the problem: I had a shift tomorrow morning at six and my girlfriend just left me. I needed to go get one drink and figure out what the hell had just happened to my life. I wouldn’t be able to sleep if I didn’t.

The last time I’d been seriously drunk with Jennifer, she wanted to fight so bad that when I didn’t raise a hand she hit herself right in front of me. I begged her to quit as she threw her fist into her face over and over again, then said, “You coward, if you won’t do it, somebody’s got to.”

We were guilty of the same strange cruelties, hurting ourselves to hurt the other, then crawling back and asking forgiveness. She often said I was too soft, and out of everything she called me, that hurt the most because it was true.

I drove to Durty Misty’s, a bar on the edge of town where I sometimes backed up country bands on bass. It was a good spot to get shitty, and while driving over there I decided that’s what I was going to do tonight.

The place was almost empty when I walked in. I’d never come here just to drink. It was always with a band on a busy night. One guy sat at the end of the bar playing Nudie Photo Hunt. A picture of a woman in a small torn bikini appeared on the screen and then broke apart into little squares. He pieced her back together before his time ran out, otherwise he would’ve lost her.

I sat down and told the bartender I wanted something that would make me hard. He was a quiet guy who looked at me like he couldn’t hear a thing I said.

“Give the boy what I’m drinking,” the man playing Photo Hunt said. He turned away from the game. There was a Daffy Duck tattoo on the side of his neck and I recognized him from the shelter. He showed up every now and then, never to eat, never to do laundry or to get help printing a résumé. Just to look around, take a few books from the free library and leave. The books he took were often classics. Lots of tattered Greek tragedies. The occasional Charlotte Lamb romance. He didn’t know who I was and I didn’t bring it up.

“Thanks,” I said.

“Try shutting your mouth more while you’re talking.” He picked his tooth with the snapped prong of a plastic fork, shook his head. “Somebody do something,” he said. “Now.”

The bartender poured whiskey, beer and pickled jalapeño brine into a blue mason jar. He mixed it with a soda straw, placed the jar in front of me and then backed it with a tiny birdbath of bourbon in the jar’s upturned lid.

“Drink half the drink,” the man said. “Then shoot the shot. And then.” He paused and considered the wall of bottles behind the bar. His pinkie and thumb winged out from his hand while three ringed fingers rubbed the tattoo into his throat. A small airplane made of beer cans hung from the ceiling on fishing line.

“And then drink the rest of it?” I said.

“No. And then fuck the rest of it.” He turned to the bartender, sucked his fingers and tapped the bone between his eyebrows. It sounded like wet wood. “Who is this sitting next to me, Bob?”

“I dunno.”

“Has he been here before?” He pressed the tattoo like he was taking his pulse.

“Yeah.”

“How do you know?”

“I dunno.”

Bob was right. I had been here many times, but I was always hiding behind my bass at the back of the band.

“Does he know what we do?”

“Probably not.”

“What do you know? Do you know shit? Tell me what you do know, Old Bob.”

Читать дальше

![Lee Jungmin - Хвала Орку 1-128 [некоммерческий перевод с корейского]](/books/33159/lee-jungmin-hvala-orku-1-thumb.webp)