“Jesus, Jenn. Was he touching her too?”

“No way. Just me. That’s how it’s always been. Look at me. I was pretty much the same when I was twelve as I am now. Just more pure. Not as busted. Can you imagine? You would’ve loved it. No other girls got the attention I got. It was because of how I looked. It wasn’t about him at all. I took it as a compliment. Still do. I remember giggling with it in my mouth. I didn’t know what else to do with it. He couldn’t help himself, you know?”

I kicked the gas and the truck swerved.

“I was just a little girl. I wouldn’t hang out with anybody like him anymore. Well, maybe not.” She poked me. “But I did have a crush on him. He wasn’t a predator. I kind of asked for it.”

“No you didn’t.”

“It split my lips when he was putting it in.”

“I’m sorry to hear that.” I didn’t know if she was fucking with me or not. She was shaking her words like they were on a string held between her teeth.

“The next day it was like I had canker sores. You like how that sounds?”

The steering wheel was slick in my hands. I kept my eyes on the road. The world outside was flying by in a blur. There was a turn ahead I knew I couldn’t make at this speed.

“In the basement the day I got my present,” she said, “I put my feet into those socks and they fit perfect. How did Good Steve know? I never had socks so nice. I promised myself I would never forget them anywhere. I promised to always keep them. Forever. It looked like a mother’s hands had made them. And maybe so. Maybe my friend’s mother, Good Steve’s wife. I’m wearing them right now. Wanna see?”

She pulled her pant leg up and flashed one of the socks. Then she vanished. I couldn’t make the turn. Daylight broke apart into pieces of shattering glass. I was alone and it was a dark night out, and freezing cold, and she wasn’t there anymore and I couldn’t protect her.

—

“Oscar, you are amazing graces.” My sister’s face against a hospital ceiling.

“What’s wrong?” I said. “Why you here, Krystal?”

But soon I realized it was me she was worried about, me why she was here and me why I was here. A cast held my arm in place, and when I tried to move it a shock of light flashed behind my eyes. I only remembered taillights I couldn’t catch.

She told me the truck flipped and landed on its side. The cops found me stuck there in my seat belt. When they looked into my window, I’d said, “Nothing to see here, ociffer.” It was all written down in the report. Apparently there were recordings of it that I was welcome to listen to. I had broken my arm and totaled my truck. The hospital released me later that day, and Krystal drove me to the station down a strip littered with stores like Virginia Cash Cow, Tony’s Terrific Title Loans and a couple doc-in-a-box places. One of them, the Med Care Clinic, was where my mom worked. At the station I picked up some of my things and learned I was being charged with a DUI, reckless driving, damage of public and private property, plus some other shit I couldn’t afford. I would’ve been in the drunk tank, but the hospital had been the first stop and my injuries were bad enough that they just let me stay. Everybody was nice about everything. They didn’t even allow me the luxury of feeling like a mean guy.

Krystal waited on a bench on the sidewalk, and when I came out she stood up and asked if I was done, like I’d been shopping. I hadn’t accomplished shit in my life, and it was embarrassing to have her here for this milestone.

“I’m done,” I said. “Done for good.”

“Oh, Oscar,” she said. She called me Oscar because the only thing I’d ever liked on Sesame Street was the Grouch. We’d spent a portion of our young lives in foster care, before a couple from the church took us in and fed us saltines and juice and let us play with their yellow Lab for a couple years, then we moved back in with our parents after my mom had finally shown the courts she could keep our lives together. There was nothing interesting about any of it. At the beginning of ninth grade I was expelled for reasons that aren’t even worth explaining. I spent the next ten years hanging around town, between my sister’s apartment and my parents’ house, sometimes living with a friend for a while until he told me I needed to start pulling my own weight, which I could never do.

“You still have a lot ahead of you,” she said.

“That’s what I’m afraid of.”

“I like when you smile,” she said. Her eyes were the color of lake ice. Her hair was blond, mine mud brown. I wondered if we came from different people.

“I’m not smiling,” I said. “My arm hurts.”

“It reminds me of Grandpa. Y’all were so much alike. I wish you could’ve known him at an older age.”

Grandpa had been a motorcycle-riding military man turned whiskey-drinking minister. He would disappear late every week and show up at his Sunday morning services smelling of it. Communion, for him, was hair of the dog. Everybody said he swore off the stuff later in life, but the damage had been done and he had maintained a haze of drunkenness in everything he did — broad gestures and a loud voice for minor occasions. At family picnics he’d make trips to the trunk to check on the spare tire, the one thing I did remember. His great tragedy, my sister liked to say, was that he couldn’t express the love he felt for me.

“Boo-hoo for him,” I always said back.

My truck had been his before he died. He gave it to Krystal and she gave it to me, telling me to keep the oil changed, which was the first thing I didn’t do.

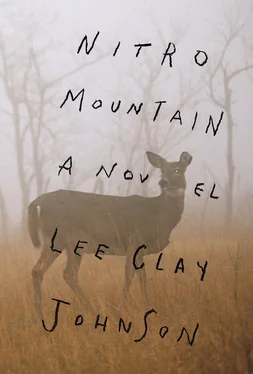

Let me say something about that truck. It was a 1980 F-150 Ranger Explorer V8 longbed with double gas tanks and an aluminum brush guard on the grille. The paint job was the color of autumn. The bench seat was the size of a sofa, like you were rolling down the road in your living room. You could sleep in the cab if you had to, and more than once I did. But those are other stories, and what hurt now was this: The one thing my grandfather had given us to show his love, I had thrown away. What did that make me?

My sister asked where I wanted to go. None of my friends were talking to me, so I told her our parents’. I hated saying it, but with my wheels gone, my arm broke and no money, I was going to need a place to sit down and figure shit out.

Krystal offered her place, but I could hear hesitation in her voice. I’d been there the last few nights. Who wants to live with their loser little brother? Who wants to see him become everything you overcame?

—

The first week wasn’t so bad. Mom worked daylong shifts at Med Care and would come home at odd hours in the evening not wearing her work clothes. Dad stayed in bed with back problems, waiting for his disability. He got stoned in the mornings and kept quiet until lunch. I’d bring him a sandwich and a couple cracked cans of Bud. Sometimes he’d send me over to the neighbors’ house, a family by the name of Habitte, to buy more pot from Nicholas, their high school son. My room hadn’t changed at all, still a couple sunken mattresses and that same rat-matted carpet underneath everything.

My Fender P Bass leaned against the wall in the corner, plugged into a Peavey practice amp. It was nice to see it there. I ran my finger along its body through the dust and drew a line of gloss across the top horn.

It was the left arm I’d broken, and my cast kept the elbow bent at such an angle that when I flipped the on switch on, sat down and put the bass in my lap, I was pretty much ready to play. I tuned it up. There was a cassette player on top of the TV that still had a practice tape in it. Mostly country and blues and rock. Loud, overstated bar stuff. I played along until my arm sizzled and sent glowing lines of pain up my wrist and into my backbone. Waiting for things to ease, I went for a walk behind the house to make sure my legs still worked.

Читать дальше

![Lee Jungmin - Хвала Орку 1-128 [некоммерческий перевод с корейского]](/books/33159/lee-jungmin-hvala-orku-1-thumb.webp)