“Your mother isn’t a rube, honey.”

“So why didn’t you tell me you knew Cross? He said you stayed at his farm.”

“Don’t call it a farm.”

It sounded like Judith was trying to trap him. She should have been a spy. “He called it a farm.”

“Farms raise food, Peter. There was a blue Rolls-Royce in the driveway, which someone had encircled with a moat. I don’t mean the moat went around the driveway, I mean it went around the car, all the way around it.”

“He gave me a picture of your Sunbeam Tiger.”

Judith laughed. “Where would I have gotten the money for a British sports car?”

“He implied it was your car.”

“What’s going on with him? Is he dying, or something?”

“Why would he be dying?”

“I got an email from him this spring. I guess he tracked me down through my website — he asked me what I’d been up to for the past thirty years. Rolf got a kick out of it, but it left me sort of sad. The guy’s got all the money in the world, all that fame and success, and he’s tracking down women he knew half a lifetime ago. I didn’t want to seem impolite or bitter, so I wrote back. He asked what you were up to. He was impressed that you’d become a doctor. ‘William Carlos Williams was a doctor,’ he said. ‘And Chekhov.’ I told him about my garden. I told him Rolf was a carpenter. I said, ‘Like Jesus.’ I was trying to be funny. He said he’d been to Jerusalem and it was full of masons, but he hadn’t seen any carpenters. I ought to forward you the messages. I wouldn’t have given him your number.”

“He called my cell.”

“He has people whose job is to bring him what he wants. It’s always been that way.”

“He offered me a job.”

“I guess you weren’t kidding about the lawyers.”

A black truck crowded Peter’s tail, but even when he slowed the truck wouldn’t pass. It loomed there, filling his rearview mirror.

“When I met him, he’d quit music. Did he mention that?”

When Peter stopped for a light, the guy in the pickup revved his engine until Peter’s car shook.

“How long did you stick around for?”

“The only reason he let me use that car was because you liked to sleep with your bassinet wedged between the seats.”

“He said he’d met me before.”

“He was fascinated with you, honey.”

The traffic light was taking forever.

“Then what happened?”

“He became a musician again. He released that album and then he was gone.”

“Which album?”

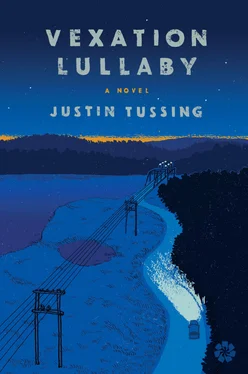

“I don’t know the name. You’d recognize it. There’s a picture of him sitting behind a table covered with junk, like a yard sale.”

Peter knew which album she was talking about — the table was beneath a streetlamp. Pinched between his thumb and forefinger, Cross held a doll-sized American flag.

Peter’s jealousy returned. “Were you in love with him?”

“What kind of question is that?”

“An obvious one.”

“I was in awe of him. I used to like his music, but being around him spoiled it. All those songs about women with perfect flaws are really about him. He’s always only been in love with some version of himself.”

When the stoplight turned green, the truck shot past. Peter felt spared.

“He might be a good person for me to know. He’s friends with Tony Ogata.”

His mother’s silence made Peter check the connection; the call counter kept tallying the seconds.

Finally Judith spoke: “You sound excited; I can hear it in your voice. I certainly don’t want to take that away from you.”

“But?”

“Don’t expect him to be human.”

Peter laughed, though he knew Judith wasn’t joking.

“It’s a shame that I’m a human doctor.”

“Maybe he’s not looking for a doctor. The important question is, What are you looking for?”

The truth: he hadn’t been looking; he’d been waiting. He’d been waiting so long he wasn’t sure if he was waiting for Lucy or if he was waiting to feel again like he had before she left.

Peter said, “I’ve got everything I want.” He didn’t see the point in upsetting his mother.

Gene has set the dining room table with cloth napkins, two forks, a knife, and a spoon. A photograph of a three-masted schooner hangs beside the table — it’s the sort of thing one encounters in the bathroom of a naval history museum. While I look around the room, Gene opens another bottle of wine, a red from California, swapping out our old glasses so the Wisconsin wine won’t contaminate the good stuff. The new bottle doesn’t seem to have anything to do with Jimmy.

He delivers the casserole to the table.

“What do you think,” Gene says, “shall we do this?”

It’s been months since I had a home-cooked meal. I eat beyond all reason.

When I push back from the table, Gene asks, “You ready for the salad?”

“I never would have pegged you as one of those salad-after-dinner kind of guys.”

As he heads back to the kitchen, he says, “It cleans the palate.”

When he returns, I stare at the salad: red lettuce, sliced red cabbage, paper-thin radish discs, and pomegranate seeds, all dressed with balsamic vinaigrette. “Is it an allusion to some lyric or something?”

“What do you mean?”

“Everything’s pink. Is that on purpose?”

“Hmm,” he says. “Did I tell you I’m color-blind?”

I feel embarrassed for both of us — me, because I’d tried to read meaning into a salad, and, in Gene’s case, that he can’t tell red from green.

Gene asks if I want to stick with wine or if I’d prefer fifteen-year-old scotch. I say he’s the boss. He comes back with a crystal decanter and two Baccarat rocks glasses.

“No cigars?” I ask.

He winks at me and disappears into the family room. When he comes back he’s carrying two aluminum cigar tubes.

I feel a guest’s responsibility to play along with him.

I start gathering the dirty dishes. I pile the plates and forks and knives, leaving the clean spoons on the table.

Gene looks at me. “There’s an apple and raisin tart in the fridge. That’s what the spoons are for.”

“I can’t do it.”

“You give up?” My friend puts his hand on my shoulder. “Don’t worry. I told you, this is a guilt-free house.”

WE CARRY THE scotch and the cigars outside. The autumn air is brisk, and after the food and the wine, I’m grateful. We climb the stairs to the little porch off the garage. He reaches a hand inside the apartment and flicks on the porch light, then turns it off again.

“You okay with the dark?”

I tell him I am.

He finishes his drink and pours another. “My head isn’t here.” He pats his pockets down, finds a lighter, and fires up the cigars. He hands me one.

“Care to talk about it?” All I want is to do is brush my teeth, slip into my borrowed bed — it’s almost a carnal urge.

At the end of his driveway a neighbor walks past with a dog.

Gene tilts his head back so that the cigar points directly above us. “Cory’s staying at a hotel.”

“Oh,” I say. “Is she alone?”

Gene leans over and spills more booze into my glass.

“She’s my wife. Of course she’s alone.”

“She could be with a sister. That’s all I meant.”

He drinks a little more from his glass. “We never went to bed angry — that’s the kiss of death.”

I make some supportive sounds.

Gene lifts his drink to his lips, then puts it down again. “Did you and your ex ever go to bed angry?”

If Patricia and I kept score, I’ve forgotten. I say, “Maybe.”

Gene taps me on the knee with the toe of his shoe. “It’s the kiss of death.”

Читать дальше