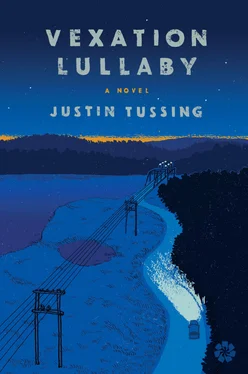

Justin Tussing

Vexation Lullaby

If you’re hired, then they want you

To do what they don’t want to.

— from “Bucolic Song” (1965)

That tow-headed tyrant marched into my shin.

He was pretending I’m invisible,

Or maybe it’s him.

— from “Best Enemy” (1977)

In the center ring the murderous cats

Pirouette on their perches.

I saw you holding your breath

While high up, near the canvas ceiling,

A family performs perilous reunions.

We were all holding our breath.

— from “Acrobat Daredevil Circus” (1979)

See the man on stage. He’s been called a genius, a lovable misanthrope, a national treasure, a fraud. The backlights make a halo of his famously unruly hair — a well-known poet, his former lover, called it “a pubic pompadour.” For five decades he played the enfant terrible; now, at seventy, he is suddenly ancient. While the final note of “Last Second Coming” snakes through the crowd, he steps forward. The upturned toe of a cowboy boot juts over the black edge. He’s a statue begging to be toppled.

The audience members — he calls them his “bloodthirsty attendants”—try to steady him with their piercing concentration. They owe him everything. After all, he’s the one who urged them to leave the dead-end towns where their parents raised them. When they drove from here to there, he rode shotgun, through the purple night, beneath the magnesium sun. When they were careful, when they were conventional, he sang to the reckless selves inside them. If not for him, would they have believed in the righteous joy of heartache? Never. His lyrics and his likeness are inked beneath their skin. Clever allusions serve as the basis for their children’s names and the passwords on their Roth IRAs. Their wills instruct that “Wayward Satellite” 1play as their bodies are lowered into the raw earth.

Look, he’s not even playing. He’s staring into the audience, or through them. Can he perceive anything beyond the spotlight’s white amnesia? Another inch forward and he’ll fall. No one has ever looked so alone as he does when he’s surrounded by people who love him.

Curls of steam rise from his head. He’s a candlewick. He’s a fuse.

A woman in the front row stretches out her hand and (no!) touches the slim ankle of his boot. His lip curls as he yanks the plug from his battered blue guitar. And then he’s gone.

Even after the houselights come up, the audience keeps chanting his name. They can beg all they want, but he’s not coming back.

Peter Silver sat in his living room watching Swim, Bike, Die , a movie about a female serial killer who targeted triathletes. The lead actress had a rather large and angular nose, not unlike Peter’s ex-girlfriend’s. He might share his observation with Lucy, if only they were still speaking. Like the killer, Lucy excelled at compartmentalization. She had broken up with him in May, despite a tacit understanding that they were nearly engaged. All summer he’d anticipated their reconciliation. More recently, he felt a kinship with the solemn folks who stood in front of the Unitarian church holding signs no one bothered to read. What Peter needed now was an exit strategy, a way to stop waiting that wouldn’t feel like he’d given up on waiting.

His phone rang. Peter felt a twinge of shame. The caller ID showed a blocked number, which meant he couldn’t rule out that it was Lucy. He willed himself to answer, lest she assume he was depressed. If she wanted to talk, he could tell her he had company. He wasn’t exceptionally depressed.

An older male voice said, “I’m trying to reach Judith Silver’s son.”

Peter was Judith’s only child; all his most effective nightmares began with an unexpected phone call. It served him right for thinking about Lucy — Judith would probably call it karma.

Judith cohabited (her word) with Rolf Stieger. The two of them shared an old prospector’s cabin in an arid canyon twenty minutes above Boulder, Colorado. They’d been together for a decade. Judith didn’t believe in marriage; she believed in coconut oil and probiotics. Rolf was Austrian — he believed in himself.

Perhaps something happened to both of them? Driving those narrow roads, a house-sized chunk of rock might flatten their car. Or they could miss a turn and wind up in that icy cataract someone named Catastrophe Creek. During Peter’s last visit, Judith’s smoke detector emitted those cricket chirps that signaled the batteries needed changing; how long had that been going? Rolf spent his days around table saws and nail guns — he couldn’t discern anything quieter than an explosion. What was Judith’s excuse? She’d always been able to shut things out. Why hadn’t Peter replaced the batteries? If his mother died in a house fire, his cheap heart would be to blame.

“Is my mother okay?” Peter had already concluded that Judith was not okay — people didn’t call about your mother when she was okay. The airport was closed for the night, but as soon as it opened he would beg the booking agent to show him mercy and put him on a plane. On the television, the killer prepared to transition onto her bike.

The caller coughed. When he spoke again, his voice sounded smaller, tentative. “Is this Peter?”

“Speaking.”

“You’re the one I’m looking for,” the man said.

Peter walked to his sink. Earlier, he’d poured a whiskey and Coke, but the drink wasn’t sitting right. He felt jittery. “Are you with a collection agency?” This wouldn’t have been the first time someone called asking him to square his mother’s debt.

“I’m a friend of Judith’s. She told me you’re a doctor.”

Peter looked back to where he’d been sitting. His wallet and his drink kept each other company on the coffee table — the caller would make him reach for one or the other.

“Who am I talking to?”

“This is Jimmy.”

The name meant nothing, but Judith subscribed to an inclusive definition of “friend”—a friend could be an intimate confidant or a person she’d spoken with at the grocery.

“Is there something I can do for you, Jimmy?” Practicing medicine conditioned a person to ask lots of obvious, almost imbecilic questions. If Peter didn’t ask the most basic questions, his patients assumed he could read their minds.

“I’m in Rochester,” said Judith’s friend Jimmy. “I was wondering if, maybe, you could set me up with a house call.”

“Did you say ‘a house call’?” Peter had never done anything of the sort, but he didn’t want to embarrass Judith’s friend.

“What’s your time worth?”

“Five thousand dollars.” In the movie, a forensic expert had just told the lead detective that the killer rode a five-thousand-dollar bike. The nightcap had been quite strong.

“Tony Ogata doesn’t charge that much.”

Tony Ogata did health segments for one of the morning shows, plus he had a call-in program on cable. His books— 30 Second Cure and the one about sex, Passionate Lifing —were perennial best sellers.

Before he’d noticed the actress’s nose, he’d barely thought about Lucy all day. It was hard for a woman to pull off an angular nose, but when it worked. . Peter said, “I don’t think Tony Ogata makes house calls either.”

“I met him in Berkeley, back when he was dosing Red Rose with amphetamines and packaging it as Focus Tea.”

“I thought you meant Tony Ogata the doctor.”

“Enough about him. You’re the guy I’m speaking to.”

Читать дальше