Welles laughs softly: a smug, paternal chuckle that Stanley doesn’t like. You mind telling me what’s funny? Stanley says.

Welles shakes his head. Let’s bear to the right here, he says.

The sidewalk carries them off Windward onto Altair Place. Streetlamps are fewer, occluded by palmtrees and eucalypts. The shadows make Welles’s face harder to read. I’m not laughing at you, he says. I was surprised by your description of my book, that’s all. The reason you cite for your choosing to read it was very similar to my reason for wanting to write it in the first place. A fascination with what is unknown. More specifically with what is invisible. It took me several years and quite a number of drafts to recognize that impulse. Now it’s pleasing to hear you say it. Let me ask you another silly question. Do you like my book, Stanley?

Stanley can’t figure out why Welles would ask this. Then he can’t figure out how to answer. He’s aware of the silence measured by their footfalls, the grunts of the little dog. To tell you the truth, he says, I never thought of it that way. I don’t know what to say to that. I read it all the way through probably two hundred times. I think I could say the whole thing out loud to you right now, from memory. But do I like it?

They’ve come to a spot where the streetlamps’ glow falls unimpeded between trees. Stanley takes a moment to scan the weedy yards of the nearby cottages. They’re near the neighborhood where he and Claudio hid from the Dogs: it feels familiar.

I like it sometimes, Stanley says. I hate it sometimes. I don’t ever get bored with it. I guess I should probably tell you that I came all the way out here to see you, Mister Welles. I told you a minute ago I was just drifting, but that ain’t the truth. About the last thing I was doing was drifting. I had to leave New York City, for some reasons that I’m not gonna get into right now, and I decided right then to track you down. It took me a lot longer than I figured. I hope it don’t upset you that I’m telling you this, or make you want to stop talking to me.

Of course not, of course not, Welles says, but Stanley can feel discomfort radiate from him in the dark. He wonders whether he’s made a mistake by not playing it cool. Then he thinks: fuck it. His leg hurts. He’s tired of pussyfooting with this guy.

Welles is quiet for a while. His pipe has gone out. Altair Place merges into Cabrillo. About half the streetlamps on the blocks ahead are burnt-out or broken. At the edge of the dim circle cast by one of the survivors two large rats are fighting; the dog tenses and raises its ears at their inaudible shrieks and squeals.

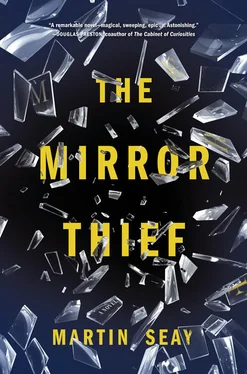

I’m glad you came to see me, Welles says. I am worried that I’m going to disappoint you. It is difficult, but probably necessary, to remember that books always know more than their authors do. They are always wiser. This is strange to say, but it’s true. Once they are in the world, they develop their own peculiar ideas. To be quite honest, I haven’t revisited the poems in The Mirror Thief in more than a year. The last time I did, I couldn’t remember quite what I’d meant by much of it. A few lines have been mysterious to me since I wrote them. Let’s turn right on Navarre.

The sidewalks are badly cracked, reduced in spots to rubble, overgrown with grasses and creeping plants. On the left, the lots slope away from the narrow street; one house has a pond in the middle of its swampy lawn, overgrown by bulrushes. As Stanley’s eyes adjust to the dimmer light he spots a gap where the plants have been flattened, and a pair of human legs protruding from the gap. The legs are motionless, clad in black boots and mud-spattered bluejeans. Down the block, a motorcycle is parked. No lights are on in the house. Stanley can smell sweet flowers somewhere nearby, but can’t see them.

I understand how you feel, Welles is saying. And why you came here. At least I think I do. I did something similar myself once, if you can believe it. Are you familiar with the work of Ezra Pound?

No sir.

You’ve never read Pound at all?

Does he write poems?

Yes he does.

I never read any poems, except for the ones in your book.

Really? Welles says. My goodness. Well. It’s as good a place to begin as any, I suppose. But you should probably borrow a few items from my library.

A few houses away a party is winding down: Stanley can hear a tangle of raucous voices through the hedge, and a hi-fi playing a bop quartet version of “It’s Only a Paper Moon.” At the next intersection, the streetsign bears a name — RIALTO — that Stanley knows from Welles’s book, and the sight of it raises hairs on his neck.

Welles is lengthening his stride, picking up the pace. When I was in Italy after the war, he says, I went to see Ezra Pound at the Disciplinary Training Center outside Pisa. He was imprisoned there, awaiting return to the United States to stand trial for treason. At the time there was every expectation he would be executed. Pound’s work was important to me at a critical time in my life. But I found his conduct during the war to be questionable. And I suppose I went to Pisa looking for some kind of explanation. Make a right turn here.

They turn onto Grand Boulevard. The street broadens, and the sky, heavy with fog, pushes between the palmtrees.

I was never able to speak with him, Welles says. No one was allowed to do that, not even the MPs. I was only able to see him very briefly. He was kept in a cell, eight feet by six, with a wooden frame and a tarpaper roof. He wore Army fatigues. He had neither belt nor shoelaces. There were more than three thousand other men in this facility, most of them hardened criminals — thieves, murderers, rapists — and almost all of them lived in the open, in tents. There were only ten cells like Pound’s. His, uniquely, was reinforced with galvanized mesh and airstrip steel. Because of the mesh walls, he was always exposed. To the sun, to the weather, to the eyes of the curious. It was always possible to see him. But no one could speak to him. In the Army’s formulation, you see, language was the weapon he had used to commit his crimes. Therefore the only language permitted him in his confinement came from his own mind, from his memory. I knew when I saw him that he had been utterly vanquished. I left Pisa very disappointed and dissatisfied. But some years later — after he had been declared insane and transferred to St. Elizabeth’s — I realized that that had been the ultimate acknowledgment of his power. For the Army to do that to him. I suppose in a sense I was fortunate to have been thwarted in speaking with him. More fortunate than you, I fear. We’ll make a left here on Riviera.

They’re nearing the oilfield now. Stanley can hear the sighs and hisses of machinery, and his sinuses churn with petroleum odors: sweet butane, bitter asphalt, fecal sulfur. In the median of a boulevard, a horsehead pump nods, throwing weird shadows under the derricks. The lights behind it wink as it rises and falls.

I was about to say, Welles says, that Pound’s silence was more powerful than any words could have been. But that is not correct. His silence was worthless. Powerless. As silence always is. Rather, it was the image of his silence. The sight of him in that cage. That has stayed with me. Reshaped, no doubt, according to the dictates of my personal mythology. Because that’s the trick, isn’t it? Our memories of language are generally stable. But how often do we remember words? It’s more often images that we recall. And images are slippery, which is why so many technologies have emerged throughout history to fix them. It’s also why successful despots tend to banish poets, or to imprison them — even poets like Pound, who are great admirers of despots — and why they tend to recruit and employ painters, sculptors, filmmakers, architects. Stop for a moment, Stanley. Let’s look at the moon.

Читать дальше