A thread of pipesmoke carries on the shifting wind. The man is singing to himself, or maybe to the dog, in a language Stanley can’t place. It’s not Claudio’s Spanish, nor the Italian of the neighbor lady back home, but it’s like them. The man is walking toward Stanley now, closing the distance. Stanley keeps silent, holds his ground. He can see the orange glow of the man’s pipe as he sucks on it, the trail of smoke, the quavering air above its bowl. The night seems brittle, as if held together by an invisible armature of glass. A single word could shatter everything.

When he’s about fifteen feet away, the man spots Stanley. He gasps, comes to a halt. The dog strains at its leash, snuffling, then springs as if snakebit and starts to bark.

Hello, Stanley says. Excuse me.

The man switches the leash to his left hand; his right hand goes behind his back. He wears a tweed jacket over a sweater, the textures of the fabrics barely discernable in the dark. Stanley swallows hard.

I didn’t see you there, the man says. You gave me a start.

It’s okay, mister. I don’t mean you no trouble.

The man’s voice is tight, but steady. He seems scared. His right hand remains hidden. You shouldn’t be alone on this beach at night, he says. It’s not safe.

Stanley holds his arms out, spreads his fingers, but the man isn’t relaxing. His outline is shrinking back, balling up, and Stanley is pretty sure he’s about to get shot. For so long he has thought of what to say at this moment, but now nothing comes. All words seem to flee from him. He feels his mouth opening, closing. Adrian Welles? he says.

The man is stock-still, silent, an inert blot on the ocean’s silver curtain. The two of them stand there, not breathing, for what seems like a long time. Stanley is aware of the dog as it growls and paws the sand.

Who are you? the man says.

When Stanley speaks again, the voice that rises to his throat is utterly unfamiliar. In past moments of mortal terror his voice has sometimes reverted to that of his younger self; at other moments, when he’s been sad or tired, he’s heard his voice grow suddenly older, as if presaging a person he might one day become. But the voice that speaks now is neither of these. It belongs to someone unknown, from another life. Listen to it closely. You will never hear this voice again.

Are you Adrian Welles? Stanley says.

But he already knows the answer, and he is no longer afraid.

Welles is backing up, winding and bunching the dog’s leash. Trembling a bit. An old man in the dark. Don’t come any closer, he says. I have a pistol, and I will use it.

I been looking for you, Mister Welles, Stanley says. I don’t mean you any harm. You or your dog. I just want to talk about your book.

Welles takes a shallow breath, lets it out. My book, he says.

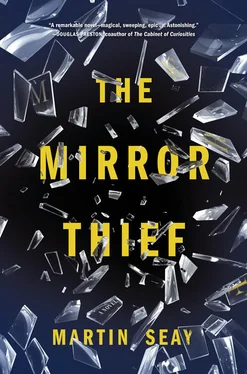

Yes sir. Your book. The Mirror Thief .

Stanley has never spoken the title aloud before. It feels clumsy in his mouth, and he regrets saying it. Loosed on the air, the words seem lifeless, insufficient for what they name.

Who are you? Welles says. Who sent you here?

This strikes Stanley as an odd question. Nobody sent me, he says. I just came.

Welles adjusts his footing on the sand. Then he says something in a foreign language. It sounds like Hebrew. Pardon me? Stanley says.

Welles repeats the phrase. It’s not Hebrew.

I’m sorry, Mister Welles, but I don’t have any goddamn idea what you just said.

What is your name, son?

I’m Stanley.

Your full name. What is it?

Stanley can’t see the man’s face well enough to read his expression. His short fingers are still absently gathering his dog’s leash. His spectacles pick up the coppery glare from the boardwalk, and both lenses are split down the middle by a dark shape, like the pupil of a cat’s eye, which Stanley realizes is his own shadow.

Glass, Stanley says. It’s Stanley Glass. Sir.

Welles’s right hand comes back into view. He wipes it against his jacket, rests it on his hip, lets it drop to his side. I saw you tonight, he says. In the café. Why didn’t you say something to me then?

I wasn’t sure it was you at first. I thought maybe, but I didn’t know. You, uh, probably oughta slack up on that leash a little bit, Mister Welles.

The leather braid has spooled thickly around Welles’s first two fingers, and the dog is twisting and backpedaling, thrashing the air with its forelegs, winched partway off the sand. Its growls have faded to a jowly sputter. Oh, Welles says. Yes.

Stanley looks out to sea, then down at the beach. He shuffles his feet, nervous again. He has so many questions, a labyrinth in his mind, one that seems at no point to intersect with the realm of normal human speech. This is much harder than he expected. I read your book, he says.

Yes.

And I have some questions about it.

Yes. All right.

I’m not real sure how to ask them, though.

At Welles’s back, the waves mutter softly. Down the shore, the foghorn sounds. It must have been sounding all night, but Stanley hasn’t noticed it.

Would you mind, Welles says, if we went back to the boardwalk? There are a lot of dope addicts and juvenile delinquents on this beach at night, and it’s better not to stay too long in the dark.

Uh, sure. That’s fine.

Welles sets out on a diagonal path away from the water; the dog scurries after him. Stanley follows, then pulls forward to walk by his side. I’m sorry if we’ve gotten off on the wrong foot, Welles says. Recent events have made me preoccupied, perhaps overmuch, with my own safety. Although not without some justification. At any rate, I hope you’ll forgive me. My evening stroll is generally south to Windward Avenue, at which point I turn back. But tonight, provided Pompey will oblige us, I think we should walk through town. I can give you a little tour. What say you, old chum?

Stanley’s opened his mouth to answer before he realizes that Welles is speaking to the dog. It marches on, not acknowledging the question, announcing every step with a tiny snort.

As they approach the streetlamps Welles’s broad face takes shape: tanned, small-nosed, creased around the mouth and across the forehead. Large blue eyes. Hair and beard flecked with white. Nothing about him is remarkable. Stanley figures him for about fifty.

They hit the boardwalk at the point where the storefront colonnade begins its long southward run. Welles stops, empties his pipe over an ashcan, and pulls a tobacco tin from an inside pocket. The dog pisses against the side of the can, stretching its hind leg skyward like a midway contortionist. Its fur is lustrous red and white; its small face is bug-eyed, short-snouted, terrifically ugly. It peeks from under velvety ears like Winston Churchill in a Maureen O’Hara wig.

You say you’ve been looking for me, Welles says. I don’t think I’ve seen you in the café before. Do you live nearby?

We’re staying in a squat off Horizon Court. Me and my pal. We been here going on three weeks now. We were working the groves in Riverside before that.

But you don’t come from Riverside originally.

No sir. My partner’s a wetback Mexican, and I’m from Brooklyn.

Brooklyn! You’re a long way from home. How old are you, if I may ask?

I’m sixteen.

Do your parents know where you are?

My dad died in Korea, Mister Welles, and my mother’s pretty well lost her mind. There’s nobody back home who’s missing me.

I am very sorry to hear that. What branch of the service was your father in?

The Army. Seventh Infantry. He fought the Japs in Okinawa and the Philippines, and he reenlisted. He got killed at Heartbreak Ridge.

He must have been very brave. He must have loved his country.

Читать дальше