Or did we? My father claimed that he would have remained in Egypt even without an income. Come to think of it I myself could not even conceive of a life outside Egypt. Our living room and in the end even the round room in the back were packed with suitcases, and still all of us were convinced this was all for show, as if by going through the motions of packing and pretending we were indeed leaving, we were merely placating a hostile deity who would, at the last instant, spare us the final leave taking and tell us it was all a test, just a test. We were never going away.

Ironically, that final year is the one I remember best, because it was the most tumultuous. I remember my grandmother and her sister, my great aunt, and I remember the bickering with neighbors and the tussles with my brother and the fights between my parents, and the loud screams when our servants fought with those of our neighbors; everyone’s temper was volcanic that year, because it was clear that things were falling apart and that we were on our last legs and still couldn’t believe that the end was near.

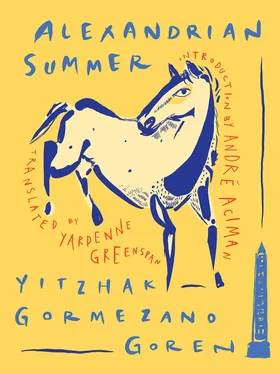

But I remember Saturdays. We weren’t religious, though I recall my great aunt turning on the radio loud on Saturday mornings to hear songs in both Yiddish and Ladino. She preferred the Ashkenazi songs and prayers, and to the sound of these songs I remember she would start preparing for Saturday’s lunch, because there were always guests on Saturdays. And even if we didn’t exaggerate the Sabbath spirit, still there was a festive air about the household, and our cook Abdou, who spoke Ladino, would put on his cleanest outfit and utter those few words in Hebrew that he knew far better than I did. In Gormezano Goren’s own words, “A pleasant breeze blew from the sea. The tumult of bathers sounded from afar: Muslims, Christians, and Jews desecrating the Sabbath. On the street, cars honked hysterically. The entire city rumbled and roared, and nevertheless a Sabbath serenity was felt all around.”

Every Alexandrian remembers this way of life and knows it is forever lost. At the very least, Alexandrian Summer gives us one final, splendid season in this mythical metropolis.

André Aciman

To my brother Haim-Victor

who was born in Alexandria,

immigrated to Israel,

lived most of his life in the United States

and considered himself a citizen of the world

1. FROM TWENTY YEARS AWAY

The Sporting Club neighborhood, the horse racing tracks beyond the tramlines. At the intersection of Rue Delta and the Corniche, by the sea, stands house number twenty-four, all seven of its stories (we used to climb up to the flat roof and shoot paper arrows down at the industrious ants running around on the sidewalk, back and forth, as if there were purpose to all this frenzy).

An Arab doorman, Badri, stands guard, squinting at the sun. His face is tan and emaciated. His little boy, Abdu, loiters at his side, helping him watch the shadows stretching over the sidewalk and the passing cars, headed toward the sea. Badri and his son welcome anyone approaching the building with an alert greeting, “ Ahalan, ya sidi ,” full of expectation: Will the guest give bakshish or not? If the guest does tip them, they escort him with bows all the way to the elevator door. If he doesn’t — they point lazily in the direction of the moldy duskiness.

The elevator is ancient, barred with black metal and faded gold openwork and bitten by reddish rust. The door slams with a metallic shake, and … a miracle! The elevator rises with a buzz, dragging with effort a looping tail that grows longer as the elevator ascends. Chilling stories have been told about power outages between the fourth and fifth floors; fights between neighbors, beginning in the stairwell, intensified in the gloom of the elevator, later to dissipate outside, in the subtropical sun that ridicules all human endeavors.

Second floor, that’s as far as I go. If you aren’t lazy, you could climb it by foot. A copper plate bearing the name of a Jewish family, descendants of Sephardic Jews from the era of the Spanish Expulsion (their last name is the name of their hometown with the suffix “ ano ”). The doorbell rings. A dark-haired and skinny servant opens the door and addresses you in lilting Mediterranean French: “ Oui, missier, quisqui voulez? ” and you stutter and ask: “Is this where Robert … Robby lives?”

The servant is surprised that a thirty-year-old man is interested in a ten-year-old boy, but he does not voice his opinion as long as he isn’t asked to. “Robby — there!” He signals toward the balcony, at the far end of the apartment. “Should I call him?”

“No, no! Please, there’s no need.”

The Arab servant looks at you with a hint of suspicion. “Who you , missier ?” and you give him your name, Hebraized to fit Israel of the 1950s, which rejected all foreign sounds. The servant does not decipher any connection between the two names. To him the strange name could be Greek or Turkish or Italian or Maltese or Armenian or French or British or even American. Alexandria is the center of the world, a cosmopolitan city. You want to add: yes, I used to be Robert, too. Twenty years ago. I’m coming from twenty years away. I won’t interrupt, I just want to watch. I won’t interfere, God forbid. No one will notice me. I just want to tell the story of one summer, a Mediterranean summer, an Alexandrian summer.

Waves of memories of that city — Alexandria — rise and recede. The story of the Alexandrian summer does not present itself easily. It is wrapped in layers of nostalgia, of oblivion, of generalizations. I search for the objective, the distinguishing. Should I tell it in first or third person? Should I use real names or give my characters aliases, adding a note along the lines of “any resemblance to real persons is purely incidental”? These may be small details, but they are the ones holding back my pen.

I want to tell you about the Hamdi-Ali family. What is it like, really, this family? The Hamdi-Ali family embodies joie de vivre , the unending Mediterranean energy. Yes, Mediterranean. And maybe it’s because of this Mediterranean-ness that I’m sitting here, telling this story. Here, in Israel, which feels much more like Eastern Europe to me. I might as well be sitting on the shore of the Baltic Sea, for all the distance I feel from the Mediterranean, which can be seen from my window in Tel Aviv. That’s why I am eager to tell the story of the Hamdi-Alis, and the story of Alexandria. A Jewish family from Cairo that came to Alexandria to spend a summer of joy. Alexandria of the days of King Farouk, with his hook-mustache and his dark glasses, the Alexandria I knew as a child, this Alexandria, which has been feeding my imagination for over twenty years, from the day I left it on December 21 st, 1951, when I was ten years old.

A storm brewed as we sailed from the port toward the lighthouse, and didn’t stop until we reached the shores of Italy. There, we were welcomed by Christmas snow. Winter was at its peak, but me, I wish to tell the story of a summer, a summer in Alexandria, an Alexandrian summer: vacation, horse races, sailboats, fishing for sea urchins, swallowing crabs, platonic (and not so platonic) romances, traffic jams, traffic jams, traffic jams, honking, honking, honking of cars and cars and more cars. All rushing toward the Corniche, the busy road overlooking the sea, where vacationers at the beach rented shacks so they wouldn’t be forced to undress in the public dressing rooms with “all those Arabs.”

Car. Car. Truck. Motorcycle. Another car. Yes, he made it! He got it down. Next: no point in listing a bicycle. Another motorcycle. Yes … it’s hard to see the license plate number from the balcony — but he has it down! What a beauty— there’s a luxury car. Quick, write down the number. DeSoto, Chrysler, Lincoln Continental. When they approach the intersection they are forced to slow down and then he can write down their numbers. And if there’s a traffic jam he can even rest for a few seconds. What a festival of sounds!

Читать дальше