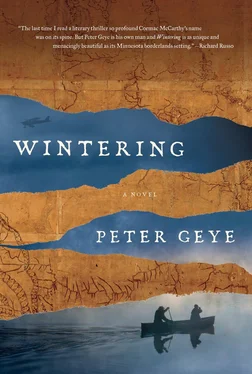

But Gus was quick to speak. “This is chart eight,” he said, pointing at the volume open in his lap. “The map of Burnt Wood Lake.”

I leaned in for a look.

The map was puckered by water from dozens of lakes and rivers and streams, from snow and rain and rising mist. The pencil lines, too, are fading, but they, at least, are not gone yet. “Someday,” Gus said, “maybe when my grandsons are old men themselves, no lines at all will be left. These beautiful wind roses. The sketches. They’ll fade right into oblivion, the paper thinning and thinning and turning to dust in somebody’s hands. Why I can take any comfort in such thoughts, I couldn’t say.”

Chart 8, excerpted from one of Thompson’s maps, shows the source of the river as a small bay on the southeastern shore of the lake. In truth, the bay was rounder and much larger than this chart suggests. “My father knew it was off-scale. One glance at a Fisher Map proved that. But he also knew that to reach our first portage we only needed to paddle to the northernmost point of the lake. From there we would continue to bear north and cross the Laurentian Divide between Lake Tramontane and Ostro Lake.” He took a sip of his coffee and peered at it closely. “That’s what he told me. As though it were simple as walking up the Lighthouse Road.”

All morning, he held that book of maps while he talked.

—

They bobbed in their canoes where the bay met the broader waters of Burnt Wood Lake, which opened up in all directions. On Thompson’s map there are only three islands, but Gus could see no fewer than a dozen as Harry pointed to one and said, “Let’s have lunch over there. We’ll plan the rest of our day after some vittles.”

So they paddled the half mile of open water to that island, trolling rubber leaches behind them. They each reeled in a few small pikes before landing on the southern shore, skirted by bedrock that rose into a tuft of scrub spruce and dormant blueberry bushes. They went ashore, and Gus gathered wood and built the cook fire while Harry readied a pot of coffee and got some rice on. They boiled the fish and when the rice was done settled into their lunch, forking bites straight from the pots.

“I suppose we’ll tire of this fish,” Harry said, “but, sweet Christ, it tastes good now.”

Gus was already sick of boiled fish and rice, but didn’t have the heart to say so.

“This time the day after tomorrow we’ll cross the divide, then on to Lake Biwanago and the old voyageurs’ highway. It’s all downhill from there.” He spoke with his mouth full of food, chewing around his words.

“How far from Biwanago?”

Harry sat on his bootheels and sipped his coffee. “No more than sixty miles as the crow flies, most of that on water. But things get a little dicey past Biwanago. The maps are truer up there, sure. But that country’ll all be strange. Country we’ve never seen, leastways. And getting colder and darker, eh? There’s that.”

He stood slowly, cracked his back, walked over to his canoe, and pulled out the birchwood calendar. He checked the notches in it — only four, though to Gus it felt like two weeks — and put it back in the pack, then turned to the maps. “Even if we get turned around up here, we’ll beat the snow.”

This had been his aim: to reach the fort before the first snow. Gus could tell it pleased him to be on schedule, even though that proved to be fallacious and meaningless. Harry was punctual to a fault. As exact as the sun- or moonrise, both of which he daily knew by heart.

I remember him winding his old Schaffhausen wristwatch at our lunch table, sandwich crumbs still on his plate. Almost nothing pleased me as much as his easy pleasure after a meal. He wound the watch then, on that island, before stepping to shore and washing their lunch dishes while Gus lay back against a rock and let the sun warm his face. In that moment he was utterly content, all misgivings arrested by both time and place.

Harry came back to their dwindling fire, poured himself the last of the coffee, and said, “How are you holding up, bud?”

Gus held his hand up to block the sun. “I’m good.”

Harry sat down and slapped him on the knee. “I should say you are. If the measure of a man’s his ability to carry a load, you’re as fine as they come.”

“Is that the measure?”

“It’s one of them.”

“But there are others?”

Harry smiled. “I sure as hell hope so.” He took a sip of coffee and lay back himself.

“So, we’ll get to Biwanago in a day or two,” Gus said. He was thinking of their route, but also found himself curious about their destination. They hadn’t talked about it since that night in the fish house. Gus had trusted that what his father’d said was true, that the plan was reasonable and sound. Why wouldn’t he? Harry had never done anything unreasonable in his life. Though it was now dawning on Gus, having reached what could have been called their first milestone, that he had no idea where in fact they were headed.

“Then up the Balsam River, along the border. A day’s paddle. Maybe less. Lots of portages and white water, but then the water gets smooth and big.” He sat up on his elbow and took another sip. “That river’s the last place we’ll know for certain where we are.”

“What does that mean?”

Harry lay back down. “Like I said, that’s new country up there. Big country. I’ve never been north of the divide. Can you believe that?”

The truth was, Gus didn’t know what the divide was, or where it was, or even what it was supposed to look like. Still, it was hard to believe that his father had never crossed it — a man who’d been to war in Europe, who could walk through any forest with the same sovereignty he had going down his hallway to the bathroom, who knew practically everything. Nothing seemed beyond him. Yet that’s exactly what he was describing: a world beyond him. Now that seemed hard to believe.

“Does it matter you’ve never crossed the divide?”

“La Vérendrye, Thompson, a hundred others like them, a thousand others, all of them passed through this neck of the woods. They all went across Biwanago. Hell, before La Vérendrye or Thompson made it, somebody else did. Some Frenchman or Scotsman three hundred years ago. When that man came through he didn’t have any map or the slightest damn notion of where he was. That’s a historical fact. That man — whoever he was — thought he was headed to the Orient, with China just up the river.” He waved at the water. “At least I know we ain’t on our way to China, eh?” He slapped Gus’s knee again and wrestled himself up off the ground. “Not only that, but he had to worry about the natives in the woods. He didn’t know what fine folks they were. And he was paddling along in a birchbark canoe. They sewed those goddamn things together with the split roots of black spruce. Roots. He didn’t have one of these stalwart vessels.” He winked and took a step toward his boat and nudged it with his toe. “ And he didn’t know when winter was coming. Hadn’t a clue what winter means around here. So does it matter that I haven’t crossed the divide? I reckon it does not. Not in comparison, leastways.”

This answer did nothing to allay Gus’s rising doubt. More to hasten it. Because Harry was dodging the question, Gus could see that even then. Perhaps he was right to.

Now he refilled our coffee mugs and stood at the kitchen counter. “To tell you the truth, I’d be hard-pressed to articulate what it was I wanted to know. Maybe just: ‘You know where we’re going, right?’ Or: ‘I’m safe with you, right?’ In any case, all I could muster was a boyish and anxious reiteration of the question that came up only moments before: ‘What do you mean, the river’s the last place we’ll know for certain where we are?’ ”

Читать дальше