Harry arched his eyebrows.

“Are you kidding me?”

“We’re in a spot here. A hell of a spot. This”—he pointed down at the water, spread his arms toward the forest and sky above, and shook the book of maps like a pastor wielding the Bible—“is not where we are.”

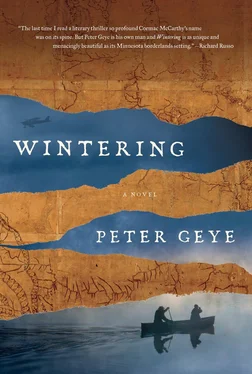

“Of course this is where we are,” Gus said. “It’s where we’re supposed to be, too.” Though they were back on course, where they wanted to be, Gus recognized it as the most dangerous place he’d ever been. He felt charged, electric, like some current as strong as the river’s was coursing through him. “The mouth of the Balsam River. Right on course.”

Harry pocketed the maps and turned to face the rapids. “I do reckon this is the Balsam, Gus. But think about how we got here. It’s blind goddamn luck. Right now, from here, we can feel our way home. Before we get into real trouble.”

Gus laughed. “Haven’t you been talking all this time about the authentic experience? About La Vérendrye and Thompson and the voyageurs? You and me. Right here. Unsure of our maps? Winter nipping at our heels? ‘We’re winterers!’ you said. You must have said it fifty times.” He said all this at once and didn’t wait for his father’s response. Instead, he pushed past him and marched back up the shoreline. When he reached his canoe he hefted the first Duluth pack from it, shouldered it, pulled the tumpline over his forehead, walked toward the edge of the sault, and dropped it. Harry hadn’t moved except to cross his arms over his ragg-wool sweater. When Gus passed again, Harry whispered his name but did nothing to stop him.

Gus passed him twice more. Once with the second pack and then with his canoe. Under the first chute, with a longer view of the rapids, he studied them for a route that obviously wasn’t there. The course was too narrow, with too many downed trees.

Harry had come to his side, holding the book of maps again. “There used to be a portage here,” he said.

“I guess some trees must’ve grown in the last hundred years,” Gus said.

“Might’ve been more than a portage. Could even have been an old logging road.”

“There was never a logging road here.”

“Gus, bud.”

“What?”

“We need to slow down. Take stock.”

“Why?”

“We’re right where we’re supposed to be. You’re right. But we’re also lost.”

“We’re not lost. We’re fucking vanished.”

Harry didn’t say anything. Instead, he turned and walked the edge of the river back up past the sault.

Gus studied the rapids again. I can float it, he thought. Fix a line, scrabble along the shoreline. As soon as he thought it, this much was settled.

He was fixing a bowline when he saw his father come tentatively around the sault. He set his pack on the shore, winded, bent over.

“You want some help?” Gus said.

“No.” Harry went back for the rest of his gear.

Gus had never seen his father overmatched before, and the sight of it spooked him even more than his own outburst had. Before he could make sense of any of it, he looped the rope over his shoulder and cinched it tight.

He pushed his canoe into the water and hadn’t taken ten steps before he realized he was at the mercy of the stream. Between the current and the heavy canoe before him, he had no recourse. His legs couldn’t keep up with the flow, and in seconds he was pulled under. The rope twisted and he was on his back on the streambed, looking up through the coursing water. He felt relief rather than panic, even found a moment to think how beautiful the blur above was before he rolled over and got to his feet. He felt electric again, as if he could have lifted from the surface of that stream like a hatching mayfly.

Now the water was waist-deep. As cold and swift as snowmelt under the Devil’s Maw. Gus searched for better footing, grabbed hold of a deadfall branch jutting from the shore, and heeled the canoe. He untangled the rope from his waist and pulled himself into shallower water. He was only halfway down the rapids but already they were losing their vigor. The water slowed and widened into a river.

When he reached the bend, the canoe settled on the river bottom and he looked back at his father, still standing under the falls. It was the greatest distance between them since they’d left home, and Gus relished it. He relished, too, that his hour’s hard work was done while Harry still had hell to pay. This, he knew, was a dangerous thought.

He turned to look west, where the river was wide and flat. The terrain climbed again on the northern shore, and white pines towered on the ridge. On the southern shore, the water seeped through duckweeds and water lilies to a muskeg thick with cedar trees. Gus opted for the northern shore, where he beached his canoe and unpacked dry clothes. When he reached into the cargo pocket of his wet pants, it was empty. No compass.

IT WAS ALMOST Christmas, and Gus had helped me up to the third floor of the apothecary. We stood at the window, looking down on the Lighthouse Road, its streetlights strung with garlands and white bulbs. The morning was shadowy, brooding, the lake still holding the darkness of the night before. We stood at the window for some time before he turned and examined the empty room.

“What’s it like being back here?” he said.

I was still looking out the window. “I’ve been back a few times already, and each time seems like it was long ago.”

“Everything seems to have happened long ago.”

“You’re not old enough to talk like that,” I told him.

He had his satchel over his shoulder. He wore a tweed coat. By every report he was a fine teacher. Every student’s favorite. He put his hands deep in his coat pockets.

“Why did you love him, Berit? What was it about him?”

“He was gentle. And funny. He was plain to see, even if most of him was hidden.” I glanced out the window again. “He loved me back. His love made me feel alive. That was very important. He was strong. I adored his strength.”

“You had that in common, eh?”

“Don’t ever mistake age for strength.”

Gus smiled his father’s smile again. They were the same, those two. Every time Gus smiled I could have taken his face in my hands and kissed him and been a younger woman again.

“I hate this place,” Gus said after a while. “I hate it because he did. Everything I love or hate. Everything I know. Everything I don’t know. It’s all because of him.”

“That can’t be true.”

“It’s true of the things that matter most.”

We looked out at the lake for a few more long minutes.

“You’re really going to make it into a museum?” he said.

“A historical society.”

He shook his head. “Sure, because this place needs its history on display.”

“Isn’t that what all these talks are, Gus? Your own history on display? For me, at least?”

“History and memory aren’t the same thing.”

“How are they different?”

He faced me. “History doesn’t abide acts of the imagination but memories depend on it. And memories are as much what we’ve forgotten as what we recall. History cannot be forgotten.”

“You don’t seem to have forgotten much.”

“I spend more time remembering than most, I guess.”

“And all this remembering, it’s taking a toll on you, isn’t it?”

He turned away. “Even though it feels good to talk about it. Isn’t that how it goes?”

“So often, yes.”

“Is it the same for you, being here? The memories?”

I looked around the room. I could picture Rebekah sitting in her rocking chair, the kitchen across the hall, could smell the herring frying in the skillet. I could see the basket of yarn and the amber light of the floor lamp. I thought of how much harder it was to stand beside him and listen to his stories, to be reminded in so many ways of his father, than it was to stand here looking at an empty room. “I don’t have any strong feelings about this place. But why would I? It was just where I waited for my life to happen. And when it finally did happen, that was somewhere else.”

Читать дальше