Peter Pišťanek - The End of Freddy

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Pišťanek - The End of Freddy» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, Издательство: Garnett Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

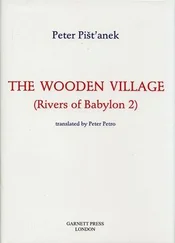

- Название:The End of Freddy

- Автор:

- Издательство:Garnett Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The End of Freddy: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The End of Freddy»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The End of Freddy — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The End of Freddy», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

When he entered the men’s house, where the Hanová and Habovka men were celebrating their punitive raid, everyone fell silent. They feared Topoľský-Cigáň’s frost-cracked, wind-burned face.

“Is there a God, priest?” Fero Topoľský-Cigáň asked the priest.

“Why do you ask?” asked the priest. “If there were no God, there’d be no us. The fact that we’re here is perfect proof that God exists.”

“And why is He here if He lets such things happen?” asked Fero, reaching for a bottle.

“God doesn’t always pay attention,” said the priest. “That’s why we have to be on guard. And if we fail, then it’s an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. That’s what Christ said. That’s why we’re Christians.”

“And how do you know this so well?” wondered Fero.

“From my father,” said the priest. “And he got it from his own father. We’ve been a priestly family ever since our forefathers came here. Our great-great-grandfather used to be a priest in the old Slovak country. That was why they used to call him Sexton, here in Junja, because of his priestly profession. That’s been our name ever since.”

“Sexton,” said Kyselica-Kuna. “An odd name. What does it mean?”

“Churches were big yurts made of stone where services were held,” said the priest. “And the sexton was the highest priest in such a church.”

“So you’re from a high priest’s family,” nodded Fero. “But tell me, where do you get all those stories of yours? How do you know so much about Christ?”

“There used to be a book once,” said the priest. “It was called Holy Scripture . But it hasn’t been seen for ages. So we pass these stories from generation to generation. My father didn’t get round to telling me all of them, as I was only a boy when the drunken Bolshevik commissar Yasin beat him to death. And so I had to find all those stories with my heart. My father comes in my dreams and teaches me all the holy things.”

The men are astounded and full of veneration.

“Christ was a great fighter,” the priest said, “and he left no wrong unpunished. Revenge was sacred to him. He had anyone who hurt him crucified. So we Christians wear the symbol of the cross to put fear in all our foes. And Slovaks are God’s chosen people. Moses was a Slovak, too. Kamil Moses-Červenka of Horná Náprava is a distant kinsman.”

“If that’s how it is,” said Geľo Todor-Lačný-Dolniak, “then it’s time to declare holy war for the Slovak nation’s rights. We’ve spent a long time in slavery and bondage, but no more! We shan’t be put off our aim. Therefore we’ll set out against the Junjan settlement of Gbb’bnäá. We’ll do to them what we did today to Gargâ. Who’s coming with me?”

Geľo’s faithful followers all raised their hands.

“But the people of Gbb’bnaa haven’t hurt us,” said a Hanová elder.

“But for some reason they make me angry,” said Geľo. “Men, do you remember the kayaks we found full of holes last year, when the whales were migrating? Well, I say that Junjans from Gbb’bnäá did it.”

The men got worked up. Anger and moonshine went to their heads. They picked up their weapons again.

“Junjans will find out what Slovaks are,” raged Geľo.

“What does Christ say about that, priest?”

“He says that you think rightly,” said the priest. “Christ taught, ‘Never hide or swallow your anger. Spread my teaching and anger will be your helpmate’.”

“Amen,” said Geľo and loaded his gun.

It was not so easy, though. The retaliatory raid, provoked by Junjans, on the former officials’ settlement Gbb’bnäá was meant to be a surprise, but many Junjans managed to escape in boats by sea. These refugees alarmed their compatriots in other Junjan settlements round the former fur-trading posts and they made war on the Slovaks.

To save his family, Geľo had to take it to a secret place, the reindeer herder Kresan’s camp. And the other men from Habovka, Hanová and other places did the same. They themselves left Habovka and withdrew deep into taiga. They became homeless outlawed fighters. Their only law was that of revenge.

As a reprisal for the massacre at Krempná, two Junjan settlements were massacred by Slovak guerrillas, since these settlements harboured government soldiers. They had been sent in by the Junjan Khan to suppress the rebellion. The army suffered great losses in combat with the wild Slovaks who were prepared for anything, being used to the terrain and its deadly conditions. The rest of the army ran away in panic. So the Khan invited foreign mercenaries to join his army and clear the guerrillas from Junja. At the head of this army, even more cruel and resolute than the Slovak resistance, he placed a man who had perhaps taken part in every putsch, civil war and rebellion of the last fifteen years, a man of mysterious origins and unfathomably devious intelligence, known in Junja by the name of Tökörnn Mäodna. This very well paid mercenary became a serious opponent for the Slovaks, but Geľo Todor-Lačný-Dolniak did not give up so easily. His ally was the wild taiga and the broken terrain of the northern coast from where he launched devastating raids against Junjans and their government mercenaries.

It soon turned out that the civil war in Junja had a charm and specific quality that made it attractive to journalists from all over the world. They gathered here in large numbers and, as is usual in such circumstances, focussed the world’s fickle attention on this insignificant little spot of land way beyond the Arctic Circle.

Among the journalists were also Czechs, who easily crossed the lines and often managed to get confidential information, not least because, unlike American or German journalists, they could understand a little of the local Slovak dialect.

The Czech journalists were the first to write about Junja and show marked sympathy for the Slovak resistance, and this was gradually taken up by journalists from other countries. The Czech public’s and government’s sympathies finally resulted in an invitation to the leaders of the rebellion to make a short visit to the Czech lands. This was not announced publicly, but intermediaries knew that Todor-Lačný-Dolniak and Sirovec-Molnár had flown to Prague to discuss, besides moral support, the possibility of material help for the rebellion.

* * *

Video Urban, too, came across the geographical name Junja for the first time only in a newspaper report of some shooting incident between local inhabitants and settlers. All the Slovak and Czech press at first kept a dignified distance from this unknown land far beyond the Arctic Circle. No one really knew anything about the country at all. The world press portrayed the indigenous people as the goodies, at first as brave, honest fighters, something between Apaches and Chechen patriots. Their enemies were portrayed as bloodthirsty foreigners having problems assimilating. Then the papers for the first time named the baddies’ leader: Geľo Todor-Lačný-Dolniak. That was strange: an odd name to find beyond the Arctic Circle. Could he be an émigré adventurer, Urban wondered. Later, the paper printed more news about the Junjan fighting, which by now had turned into a veritable bloodbath. At first the impression given was that the enemy, the destroyers, was the Slovak minority. Slovaks abroad. But how had they got there, Urban wondered.

The most surprising fact was that as the world slowly learned the full truth about the fighting in Junja, the position of the Slovak Press Agency remained, in agreement with the Slovak Republic’s official position, pro-Junjan. To confirm this, the Prime Minister invited Okhlann Üncmüñć, Chairman of the Supreme Council of the Junjan Khanate, to visit Slovakia. The joint statement of both sides was as follows: “The Slovak Republic considers events in Junja to be an internal affair of the Junjan Khanate and condemns efforts by the Czechs to influence events by overt and covert support of anti-government terrorists who happen to be ethnically similar to the population of Slovakia.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The End of Freddy»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The End of Freddy» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The End of Freddy» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.