I told Marcelo we should think it over, that it all sounded too complicated, and that for the time being I only needed the first excuse, the one I’d broadly outlined and he’d refined with a skill that revealed — against all expectations — a habit of lying, and even a perverse delight in doing so. As a coda to our conversation, Marcelo said that if I got fed up with living at my mom’s house, I could spend a few days at his place in the residential estate of Puerta del Aire. It wasn’t particularly pleasant, he said, or close to the center of town, but if what I needed was to be alone and think my own thoughts, it was a good spot with no distractions. I didn’t know if he was proposing this because he’d realized that our shared lie would oblige him to live with me for a longer period and, hence, be a little discreet about his sexual relations, or because he genuinely wanted me to attain spiritual maturity through living ascetically; my guess is that it had more to do with the former. In any case, I decided to take him at his word later on, not because I thought any good would come from staying in Puerta del Aire, but because I took pity on him and imagined that neither he nor my mother would want me vomiting up her thick milk every night for much longer.

The whole conversation took place in the street while Marcelo and I were walking to the store, at Adela’s request, to buy some things we needed for the New Year’s Eve dinner. I explained to him that I’d already told Cecilia the lie, so all that was needed to put the plan into action was to tell it to my mother when we got back. On January 2, Cecilia would get into the red car and travel, in the reverse direction, the highway that had drawn so many reflections from me on the outbound journey.

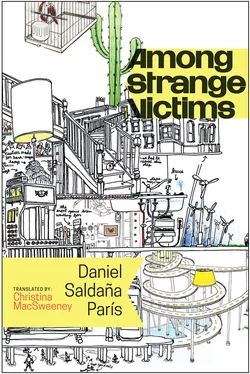

13

13

And so it went: on New Year’s Eve we had a meager, vegetarian dinner — Marcelo had complained about the Christmas turkey and suggested cooking something without meat. And Cecilia got into the red car and set off back to routine, and my vacation changed from being a temporary, reversible rest to a limbo of idleness, promising great satisfaction, or great disillusion, or simply hours and hours of looking at the wall. And my mom returned to her university work, which didn’t take up too much of her time, and Marcelo went back to his small office at the university and spoke to Velásquez and told him about our lie, hatched from his supposed book. And I woke up alone in the morning in Adela’s house without having heard anything too upsetting in the night — no swimming contest, no asthmatic child — and sat by the cactus garden and felt myself to be a little freer, a little lonelier, and a little older, in the venerable sense of old age, which can, I imagine, be positive, to the extent that it allows you — will allow me, if I get there — to think only about the things each morning offers. In my case, the morning offered me the difficult choice between either staying in my mom’s house or moving into Puerta del Aire. But instead of weighing these options, as I would when making a decision during office hours, when one considers the pros and cons and makes a rational decision based on a quantitative calculation — more pros and fewer cons beats fewer pros and more cons — I endeavored to sit silently for a few hours and then suddenly decide one way or the other, basing this decision on, for example, climatic conditions — things related to the moment, which is always unfathomable and irrational. And I wanted it to be the moment, and perhaps the climate — not the climate as a matter of clouds, but something else: the climate defined as the totality of objects that surrounded me, the material climate that is derived or emanates from the harmony and secret communication between inorganic things; objects are traitorous — that would make me suddenly decide to go to Puerta del Aire, to Marcelo’s tasteless little house, where, what’s more (now come the pros and cons), away from any watchful eye, it would be easier for me to pretend I was copyediting Velásquez’s book. And where it would be easier for me, I supposed, to quench my thirst without having recourse to my mother’s thick milk, the thick, maternal milk that comes in bottles with the labels falling off. And where, moreover, it would be easier for me to avoid the reasons for my sleeplessness — swimmers doing the crawl, children with asthma — and give free rein to my collector’s impulse, which is neither a destructive impulse nor a creative impulse, but simply this: an impulse to accumulate without any great degree of coherence, an impulse to conserve and find a space for the things that already exist, that apparently have always existed.

14

14

Marcelo rings the doorbell of his own house, in which I’ve installed myself. The bell emits a shrill, piercing screech that continues going round and round the spiral of my ear long after the external sound has faded, like the way the sea continues to be heard in the spirals of seashells, or so they say. I know it’s Marcelo because no one else has rung the doorbell; no one else would, or at least I can’t think of anyone who would. I’ve been here for two days, and no one has rung the doorbell. Just Marcelo, yesterday, who rang and came in to see how things were, to see, I suppose, if I’d destroyed the horrendous furniture or had a problem with the security guard, to whom Marcelo has, apparently, taken a certain dislike. Or it could be that Marcelo came yesterday and, as seems likely from the sound of the doorbell, has come again today because he’s genuinely interested in what’s happening to me; in what’s happening to me inside my head, I mean. This is an option that seems — against the grain of my habitual skepticism in relation to the human species in general — probable, and I say this because yesterday Marcelo sat in the armchair opposite me, in the afternoon, at this hour, after leaving the university, where he’d probably done nothing, or at least nothing of any note, nothing worth mentioning: he didn’t mention anything he might have done, or even thought. He sat, as I said, opposite me, in the armchair opposite the armchair where I myself am now sitting, and asked, in a tone of voice new to me — more serious or more sincere, perhaps, if sincerity can be identified in a tone of voice — what I’d been thinking. “What have you been thinking?” he asked, as if he was really interested in what I think, as if I myself was interested in what I think and was capable of retaining and then transmitting it and letting my thought fall into the other person’s mind and then germinate, timidly, and grow into a tree, or at least a small plant of thought, of ideas, of communication. Something of that kind, so they say, though using less hackneyed similes, is possible between people, though it’s never happened to me.

Marcelo rings the doorbell of his own house, a dwelling that was never, strictly speaking, completely his own since just as soon as he came to Los Girasoles, he says, he realized that renting this glorified apartment (it would be an exaggeration to call it a house) had been a mistake, and it was perhaps for that reason he had sought, or at least opened himself to the possibility of, a love affair, of being infatuated by a local, or reasonably local woman like my mother, who wasn’t born in this town but has lived here for some years — I’ve forgotten how many — and, in any case, is more local than Marcelo since she is at least from this country. Marcelo rings the doorbell of his glorified apartment and, hearing the bell, I realize his glorified apartment is, in fact, after only a few days, my glorified apartment. And I say that it is, in fact, mine because I have a proverbial ability for setting up home, for occupying a space in a human, cultural way, for impregnating the space with the smell of my actions, which don’t need too much repetition to become everyday actions — it’s enough for me to do the same thing twice, on two successive days, for it to become a ritual, identifiable activity, my way of inhabiting that portion of air in this house in Puerta del Aire, which is the not unpoetic name with which they christened this awful, soulless residential estate. But the glorified apartment is not only mine in the, let’s say, intangible sense of my having actively appropriated its space but also in the, let’s call it tangible sense of having placed in that space a series of objects (not many) that indicate an organizing mind different from Marcelo’s — objects are traitorous. There are, for example, some pieces of volcanic, or at least porous — I know nothing about geology — rock that I found in the sun-scorched streets of Puerta del Aire. Pieces of rock that I liked, I’m not quite sure why, and brought here and distributed around the apartment in an order that could be described as random, though is, in some way, comforting: I am comforted by the visual continuity the pieces of rock confer on the whole house — they are, you could say, its decorative focus.

Читать дальше

13

13