Sophie struggled to her feet. She went into her study, dug out a blank notebook, booted up her laptop and began her investigations.

There is something in the corner of my room, in the dark. A shadow.

I know what it is, but I don’t look. I can’t sleep; I’m afraid. I lie in bed, the blankets pulled up to my chin. It’s the middle of the night and tomorrow — no, today, to be precise — is the day of the interview. I would normally watch TV on long, pale nights like this when sleep shuns me. But I can’t go drifting on an ungovernable tide of information; I want to be able to control the thoughts and images that enter my head.

When I woke up, and before I opened my eyes and looked at the clock, I had hoped that it wasn’t the witching hour — that terrible time between three and four in the morning. Dark thoughts cling to me like leeches whenever I wake then. It’s the same with everyone. It’s natural to feel awful in the witching hour, when night is at its coldest and the human body is at its lowest ebb. Blood pressure, metabolism, body temperature — everything drops. No wonder more people are said to die at that time than at any other.

After I had pondered all this, I opened my eyes and tried to make out the digits on my clock. I swallowed hard; it had just turned three, of course.

Now I’m lying here, letting the words melt on my tongue: witching hour . I’m familiar with it; I know it well. But today is different, even darker, even deeper, than usual. The shadow in the corner stirs. I only glimpse it from the corner of my eye. It smells of bewilderment and fear and blood. A few hours now before the interview begins.

I try to compose myself. I tell myself I can make it, that Victor Lenzen will be under as much pressure as me, if not more. He has a great deal to lose — his career, his family, his freedom. That is my advantage: that I have nothing to lose. But it makes no difference to my fear.

There are people who would think me crazy if they knew what I was planning to do. I am aware of how inconsistently I am acting. I’m terrified, and yet I summon a murderer to my house. I feel vulnerable, but even so I believe I am going to win the day. Things can’t get any worse in my life. And yet I’m afraid of losing it.

I switch on the bedside light, as if by doing so I could dispel my gloomy thoughts. I snuggle up under the duvet, but shiver at the same time. I reach out for the battered old book of poems on my bedside table, sent to me years ago by some fan. I run my fingers over the binding, exploring the tears and creases in the thick paper. I was always a woman of prose rather than poetry, but this book has more than once brought me succor. It falls open at the passage in Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” which I have read so often that the book has taken note of it.

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

It is good to read about somebody who feels the way I do. Once again, my thoughts stray to Lenzen. I can’t begin to imagine how the day ahead will turn out. Much as I’m dreading it, I can’t wait for it to dawn at last. The waiting around and the uncertainty are gnawing away at me. Daybreak seems so distant. I long for the sun, for its light.

I sit up cross-legged and drape the duvet over my shoulders like a cloak. I leaf through the book and find the passage I was looking for.

To behold the day-break!

The little light fades the immense and diaphanous shadows, The air tastes good to my palate.

In the darkest hour of the night, I warm myself at a sunrise described by an American poet well over a hundred years ago, and I feel better, and less cold.

Then I see it again, on the edge of my vision. The shadow in the dark corner of my bedroom is moving.

I summon up all my courage and walk unsteadily toward it with outstretched hand. My fingers meet only with whitewashed wall. The corner of my bedroom is empty — only a faint smell of caged predator hangs in the air.

The day that I have longed for and dreaded in equal measure has arrived.

After warm weather these last few days, this morning is cool and clear. Thick frost covers the meadow and sparkles seductively in the sun. Children will find frozen puddles on their way to school and skid around on them, maybe poking them with the tips of their boots until they crack.

I have no time to take pleasure in the view. I have a lot to do before Lenzen arrives at midday.

I will be prepared.

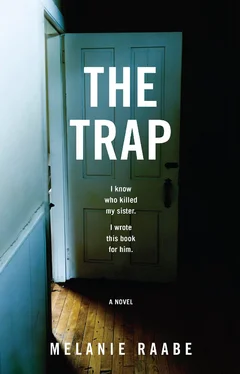

A trap is a device to catch or kill.

A good trap should be two things: foolproof and simple.

I’m in the dining room, looking at the caterers’ food I’ve had delivered. There’s enough to feed an army, but there will only be three of us: Lenzen, the photographer he’s bringing with him, and me. I am, however, confident that the photographer won’t need more than an hour to shoot his pictures and will then leave us alone.

The light lunch consists of salads and other titbits prettily served in little jars, and wraps filled with vegetables and chicken. There are small pieces of cake set out on elegant porcelain and a nicely arranged fruit basket. I didn’t choose any of this food on the grounds of taste; my sole criterion was whether the person eating it was likely to leave a decent sample of DNA behind. The salad and cake are ideal. You can’t eat them without using a fork and leaving traces of saliva behind. The basket of fruit is likewise promising. If Lenzen should bite into an apple, I could gather up the remains as soon as he’d gone, and have them analyzed. As for the wraps: you can hardly eat them without making quite a mess with the sauce, which comes oozing out when you bite into them, so it’s likely anyone having one will wipe his fingers and mouth on a napkin afterward. In that eventuality, I can expect usable traces of DNA on the napkin.

I remove the cutlery and napkins provided by the caterers. Then I pull on disposable latex gloves, take my own salad forks and cake spoons that I sterilized yesterday evening and arrange them on the serving trolley. Finally I open a new packet of paper napkins. I step back and survey my work. The food looks incredibly appetizing. Perfect.

I pull off the gloves, throw them in the kitchen bin, put on new ones and take the only ashtray I have in the house out of the cupboard. I place it on the dining table where Lenzen and I are to sit. I have already laid out a few advance copies of my book, a thermal coffeepot, cream, sugar, cups and spoons, as well as bottles of mineral water and glasses.

The ashtray is by far the most important object on the table. I have discovered that Lenzen smokes. If he leaves a cigarette butt it will be like winning the lottery, so he shouldn’t have to ask my permission to smoke — he should find an ashtray ready and waiting on the table.

I glance at my phone. I still have loads of time before Lenzen arrives. I breathe in and out, pull off the second pair of gloves and throw them away too. Then I collapse onto the sofa in the living room and go through my mental to-do list. I soon come to the conclusion that I’ve taken care of everything that needed doing.

I look about me. The cameras and microphones that were installed for me a few days ago by two discreet members of a security company really are invisible. Good. If I can’t see them, even though I know they are there, then Lenzen certainly won’t be able to. My entire ground floor is bugged. It may seem naive to presume that Lenzen is going to incriminate himself, but if psychologists — and other experts like Dr. Christensen — are to be believed, some murderers are secretly longing to do just that: to confess.

Читать дальше