So now we’re sitting face-to-face. I’ve done my homework. Christensen has suggested demonstrating his method of interrogation on me: that seemed the most straightforward way of showing me what it feels like to be put through the Reid technique. He began the consultation by asking me to think of something I was particularly ashamed of — something that I never wanted to reveal. Of course, I came up with something, just as anybody would have done, and now Christensen is trying to wheedle the information out of me.

He’s getting closer. Over an hour ago he understood that it’s something to do with my family. His questions are getting more penetrating and I am getting thinner-skinned. To begin with, I felt indifference toward Christensen, maybe even sympathy. I have come to detest him: for his questions, for his persistence, for the fact that he won’t leave me in peace. He instructs me to sit down again when I want to go to the loo. Reprimands me every time I want to drink anything. I’m not allowed to drink until I’ve confessed. When he saw me wrap my arms around myself because I was shivering, he opened all the windows in the room.

Christensen has the habit of constantly clearing his throat. I didn’t notice at first, but when I did I dismissed it as an endearing mannerism. Now it’s driving me crazy, and every time he does it I want to jump up and yell at him to bloody well stop it. Stress brings out the worst in me — my irritability, my quick temper. Everyone has triggers. Mine are mainly acoustic: throat clearing, sniffing, or that noise when someone chews gum and keeps popping the bubbles. Anna was always doing that, often only because she knew it annoyed me — I could have killed her!

The thought has hardly taken shape in my mind before I’m ashamed of myself. How could I think such a thing? Christensen is tenderizing me; I’m starting to yield. I’m tired, I’m cold, I’m hungry, I’m thirsty. Following Christensen’s instructions, I didn’t sleep last night and have hardly eaten all day. If I were in custody under his supervision, says Christensen, he’d have made damn sure that I went hungry and got as little sleep as possible.

“It’s astonishing how quickly we start to crack up when we’re deprived of the mainstays of our physical well-being,” Christensen had explained to me on the phone.

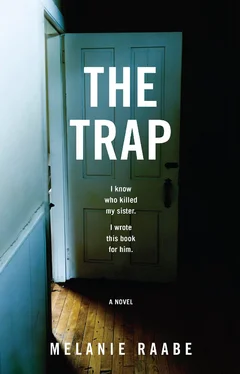

I am not, it is true, going to be in a position to deprive my sister’s murderer of food or sleep, but I am at least learning to cope better in situations of tremendous stress. Who knows whether I’ll sleep at all in the nights before the interview with Lenzen — or manage to eat.

Christensen’s questions go on and on. I’m sick of them. I’m tired. Above all, I’m emotionally exhausted. I’d really like to tell him everything, to get it over and done with. And why not — it’s only an exercise, after all.

But I realize this is a dangerous way of thinking. Just the kind of self-justification that might trigger my capitulation. I notice that I’m sweating, in spite of the cold.

When Christensen finally leaves, I feel as if I’ve been through a mincer. Physically and mentally drained. Burnt out. Empty.

“Everyone has a breaking point,” he’d said to me toward the end of the consultation. “Some people reach theirs sooner, others later. It all depends on how much a secret is worth protecting, or what far-reaching consequences a confession might have.”

I open the front door to see him out. It’s late. He lays a genial hand on my shoulder and I try my hardest not to flinch at the contact.

“You’ve done a good job today,” he says. “You’re a tough nut.”

I wonder whether I’d feel better if I’d given in — more relieved. Part of me wanted to share my secret. I wonder whether people like Victor Lenzen feel the same. I wanted to confess.

But I didn’t reveal my secret. I didn’t reach my breaking point.

I try to recover my equilibrium. I close the windows and warm myself. I eat and drink. I have a shower and wash away the cold sweat. Only sleep will have to wait. I divide my day up strictly. I write early in the morning, then I do research and work out, and after that I return to my desk, often working far on into the night. I’m so exhausted I’d love to take tonight off, but there’s still so much to be done if I’m to meet the deadline — and I have to meet the deadline.

I sit down at my desk and open my laptop. If I’m going to proceed in sequence, I must now write something difficult about grief and feelings of guilt. I stare at the empty screen. I can’t, not now. I want to write something nice today, after such a strenuous day — one nice chapter in this horrific story.

I sit and think. I remember what I was like twelve years ago — what I felt, what it felt like to be me. Another life. I think back to a particular night in my old flat and notice a wry smile creep across my face. I had forgotten what it’s like to have a happy memory. I take a deep breath and begin to write, immersing myself in my old life. I see everything in all its colors, hear a familiar voice, breathe in the smell of my old home — relive everything. It feels lovely — almost real. I don’t want to return to the present when I get to the end of the chapter, but I have no choice. It is deep into the night when I look up from the laptop. I am hungry and thirsty. I press save and close the file. But I can’t resist opening it again, rereading and warming myself at the memory of life as it once was.

After I’ve read it through, I tell myself that it’s too private, that this book isn’t about me. I’m writing it for Anna, not for myself, and nice chapters have no business to be there. I close the file, about to drag it to Trash, when I change my mind; I create a new folder called “Nina Simone” and put it in there. I open a new Word document and psych myself up to write what has to be written next.

Not tomorrow, but now.

9

JONAS

On the short flight of steps up to his house, someone was sitting, smoking. It had been dark for some time but, as Jonas rounded the corner, he could see the figure from a distance. As he got nearer, he realized that it was a woman. She took a drag on her cigarette and her face lit up in the glow. It was the witness he’d met the other day. Jonas’s heart began to beat faster. What was she doing here?

He felt uneasy about encountering her like this. He was drenched in sweat from head to foot. Mia was out with her girlfriends, so he’d finally taken the time to go for a long jog in the nearby woods and mull things over. He’d pondered on how swiftly things had changed between him and Mia — and unprovoked. No lies, no affairs, not even the usual arguments about having children or buying a house. No major scenes of any kind. They still liked one another a lot. But they no longer loved one another.

The realization had hit him harder than the disclosure of an affair. Presumably he was to blame because, even leaving aside what had been going on in their relationship, he’d been feeling odd lately, kind of cut off from life, as if in a diving bell. It wasn’t Mia’s fault; the feeling had been dogging him for ages, a vague phantom pain that made him afraid he’d never be able to understand anyone, or be understood. He felt it at work. He felt it when he was talking to his friends. He’d felt it at the theater.

Sometimes he wondered whether this diving-bell feeling was normal, whether this was what it felt like to enter a midlife crisis. But, then, it was a bit early for that. He’d only recently turned thirty.

Jonas brushed the thought away, took a deep breath and approached the woman with the cigarette.

“Good evening,” she said.

“Good evening,” Jonas replied. “What are you doing here, Frau…”

Читать дальше