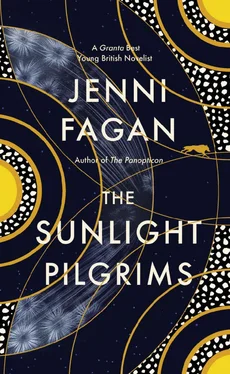

Jenni Fagan

The Sunlight Pilgrims

Set in a Scottish caravan park during a freak winter — it is snowing in Jerusalem, the Thames is overflowing, and an iceberg is expected to arrive off the coast of Britain — The Sunlight Pilgrims tells the story of a small community living through what people have begun to think is the end of times. Bodies are found frozen in the street with their eyes open, and schooling and health care are run primarily on a voluntary basis in response to economic collapse. Dylan, a refugee from panic-stricken London who is grieving for his mother and his grandmother, arrives in the caravan park in the middle of the night — to begin his life anew. Under the lights of the aurora borealis, he is drawn to his neighbour Constance, a woman who is known for having two lovers; her eleven-year-old daughter Stella, who is struggling to navigate changes in her own life; and elderly Barnacle, so crippled that he walks facing the earth. But as the temperature drops, daily life carries on: people get out of bed, they make a cup of tea, they fall in love, they complicate.

The Sunlight Pilgrims , the thrilling follow-up to The Panopticon , is a humane, sad, funny, shimmeringly odd and beautiful novel about absence, about the unknowability of mothers. It is a story about people in extreme circumstances finding one another, and finding themselves.

JENNI FAGAN was born in Scotland, and lives in Edinburgh. She graduated from Greenwich University with the highest possible mark for a student of Creative Writing, and won a scholarship to the Royal Holloway MFA. A published poet, she has won awards from Creative Scotland, Dewar Arts, and Scottish Screen among others. She has twice been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and was shortlisted for the Dundee International Book Prize, the Desmond Elliott Prize and the James Tait Black Prize. Jenni was selected as one of the Granta ’s Best Young British Novelists in 2013 after the publication of her highly acclaimed debut novel The Panopticon .

For Boo,

& Christian Downes

THERE ARE three suns in the sky and it is the last day of autumn — perhaps for ever. Sun dogs. Phantom suns. Parhelia. They mark the arrival of the most extreme winter for 200 years. Roads jam with people trying to stock up on fuel, food, water. Some say it is the end of times. Polar caps are melting. Salinity in the ocean is at an all-time low. The North Atlantic Drift is slowing.

Government scientists say the key word is planet. They take care to remind the media that planets, by nature, are unpredictable. What did we expect? Icicles will grow to the size of narwhal tusks, or the long bony finger of winter herself. There will be frost flowers. Penitentes. Blin drift. Owerblaw. Skirlie. Eighre. Haar-frost. A four-month plummet will conclude with temperatures as low as minus forty or even minus fifty. Even in appropriate layers. Even then. It is inadvisable. Corpses will be found staring into a snowy maelstrom. A van will arrive, lift the frozen ones up, drive them to the city morgue — it takes two weeks to defrost a fully grown man. Environmentalists gather outside embassies while religious leaders claim that their particular God is about to wreak a righteous vengeance for our sins — a prophecy foretold.

The North Atlantic Drift is cooling and Dylan MacRae has just arrived in Clachan Fells caravan park and there are three suns in the sky.

That’s how it all begins.

On Ash Lane, along a row of silver bullet caravans, a blackbird lands on a fence post. His eyes reflect a vast mountain range. Standing at the back of no. 9 looking toward the parhelia are Constance Fairbairn, her child Stella and the Incomer. Neighbours step out onto porches and everyone is unusually quiet, nodding to each other instead of saying hello.

Stella imagines the brightest sun is for her, the second is for her mother and the last is for clarity, most recently lost. Her mother wants this back in their lives, but the child does not know why she should want it so much when clarity is no ally. It isn’t any kind of a companion at all. Stella stands, arms folded, frowning — right in between her mother and the Incomer, while three suns climb higher in the sky.

Constance does not see her child in the parhelia. She sees two lost lovers and herself in the middle — reflecting light. Caleb will be in Lisbon from now on and, after this last fight, she will never speak to him again. Alistair is back with his wife. Three suns to herald the beginning of a great storm. How very fleeting — any moment of stability. Constance is weary from matters of the heart but more so from worry for her child.

Dylan MacRae shades his gaze. He wears a fisherman’s jumper and a deerstalker hat, Chelsea boots, tailored trousers, he is overly tattooed, immodestly bearded — he is clearly taller than a man was ever meant to be. He rolls a cigarette and lights it. His eyes are red-rimmed in this brightness and he is dazed from seeing a woman polish the moon. In all his days. Three suns, seven mountains and so, so close to the sea.

Dylan looks up at the parhelia and he sees Constance, her child and him.

There is a curious coruscation to the Incomer’s eyes. The mother stacks wood. The child has two spirits. The entire landscape repaints itself in gold — crags, gorse bushes, the burn, sheep, a glint of waterfalls, fences, stiles, whitehouses, the bothy and right up there on the seventh sister there is a stag; the train tracks curve around the lower mountains — even the scarecrows appear momentarily cast in metal.

The blackbird flies away without song.

The child gazes toward the suns.

Stella keeps her focus; this way she won’t be blinded but she will not have to look away for some time. She focuses, trying to absorb the suns’ energy deep into her cells so when they descend into the darkest winter for 200 years, in the quietest minutes, when the whole world experiences a total absence of light — she will glow, and glow, and glow.

Snowflakes cartwheel out of the sky — hundreds, thousands, millions — the three suns fade as caravan doors click shut, all along Ash Lane.

Part I. November 2020, −6 degrees

THEY ARE quite clear about it. They use short declarative statements. Capital letters. Red ink. Some points are underlined. In summation: they want everything. It is the end. Dylan uses nail scissors to trim the longest stragglers on his beard, he bends over a row of sinks in the Ladies and splashes water on his face. He has acted out many roles in front of these mirrors: Jedi, Goonie, zombie, vengeful telekinetic teen — a Soho kid growing up in an art-house cinema: he’d lie onstage in his pyjamas watching stars glide across the ceiling for hours. His grandmother used to say that they were keepers of a conclave, a place where people came to feel momentarily safe, to remember who they once were — a thing so often ignored (out there) but in here: lights, camera, action!

Dylan pulls on his jumper and heads for the empty foyer. The ticket stall is musty. A trail of empty gin glasses lead to his projection booth. He briefly recalls toasting Tom and Jerry, Man Ray, Herzog and Lynch, Besson and Bergman, the girls from the peep-show next door, Hansel, Gretel and all of their friends. He picks up the letter again. Even if she had told him, he couldn’t have done anything. The account is empty. There is less than nothing. The deficit has so many figures he quit counting. A pile of unpaid bills are stacked neatly in Vivienne’s vintage sewing box and when he got back from the crematorium he found an envelope containing the deeds for a caravan 578.3 miles away, with a pink Post-it note and her scrawl: Bought for cash — no record in any of our accounts. Mum x.

Читать дальше