Susanna Gregory

THE KILLER OF PILGRIMS

2010

Early Spring 1350, Canterbury

At last, the Great Pestilence had relinquished its deadly grip. There had not been a new case in three months, and people were allowing themselves to hope that it had gone for good. It had left behind a terrible mark, though. Whole villages lay empty, houses were abandoned and derelict, weeds choked the fields, and every churchyard was full to overflowing with the dead.

The previous December, the Archbishop of Canterbury had written to the Bishop of London, suggesting it was time to thank God for delivering His people from the dreadful scourge. The devout had hastened to comply – it would not do to be ungracious, and provoke a second wave of the dreadful disease. Some folk, feeling prayers were not enough, had opted to go on pilgrimages, too, to make sure the Almighty truly appreciated the full extent of their gratitude.

Unfortunately, undertaking such journeys was no easy matter. The devastating sickness meant roads and bridges had been allowed to fall into disrepair, and nature had taken its toll, too – even the most important routes were now blocked by fallen trees, encroached upon by brambles, or washed away by rain and floods. In places, they had disappeared completely, leaving the traveller to wander hopelessly until some helpful local pointed him in the right direction.

Of course, not everyone on the King’s highways was friendly. Bands of brigands roamed, safe in the knowledge that the forces of law and order had been seriously depleted by death. Because of this, sensible pilgrims travelled in groups, seeking safety in numbers.

The party that paused at the top of a hill to gaze at Canterbury in the distance had been lucky. The weather had been kind, the tracks easy to follow, and would-be robbers repelled without too much trouble. They were a disparate crowd, comprising clerics, soldiers, merchants and paupers, and they had stayed together only because it would have been dangerous to do otherwise. The sick man had scant respect for any of them, and longed to reach St Thomas Becket’s shrine, so he could dispense with their tiresome company. He waited impatiently for them to finish their gawping and their self-serving prayers, eager to be on his way.

Canterbury itself was hectic, noisy and filthy. The sick man supposed its streets were cobbled, but they were so deeply carpeted in manure, rubbish and discarded scraps of food that it was impossible to tell. The stench was overwhelming, and made his eyes water so much that he could barely see the cathedral’s soaring towers and delicate pinnacles ahead.

Once he had battled his way through the array of beggars who clustered around the door, the sick man knelt and gave thanks for his safe arrival. Then he rose and walked slowly through the massive nave. The shrine was at the far end, a cluster of columns, filigreed arches and precious stones. It, too, was encircled by a heaving mass of humanity, all clamouring pleas and demands. More candles than he had ever seen in one place were burning – offerings from grateful penitents – and their collective glow was so bright that it dazzled the eyes.

The cathedral’s priests were moving through the throng, accepting gifts of money, jewellery, food and whatever else had been brought for the saint’s delectation. No wonder the place was so wealthy, the sick man thought wryly, watching his travelling companions pay their tributes.

The hubbub around the tomb was far too distracting for meaningful prayer, so he wandered through the cathedral’s echoing aisles, thinking to wait for a quieter moment before asking for a cure. Little stalls had been set up there, selling food, books, candles, clothing and anything else that travellers might need. The last booth was peddling pilgrim ‘badges’, its wares laid out in neat lines on a smart black cloth. There were crude pewter images of St Thomas that could be pinned on hats or cloaks, to tell all who saw them that their wearers had visited the shrine, and there were expensive ampoules of ‘Becket water’.

‘These little phials each contain a drop of the saint’s blood,’ declared the pardoner who owned the display. ‘That means they are sacred. Relics in their own right.’

Impressed, the sick man inspected them more closely. Many were works of art, the tiny bottles enmeshed in delicate strands of gold and silver. The liquid inside was faintly pink – blood mixed with holy water.

‘What are these?’ he asked, pointing to a row of scallop shells.

‘Tokens from the shrine of St James at Santiago de Compostela,’ replied the pardoner, a handsome man with very white teeth. He grinned, sensing a sale. ‘And here is a cross from Jerusalem, and a leaden image of the Virgin from Rocamadour in France.’

‘But if I wore those, everyone who saw them would assume I had been to these places,’ said the sick man, bemused. ‘And I have not. Not yet, at least.’

The pardoner lowered his voice conspiratorially. ‘These are sacred things, so that even touching them will confer blessings on you. And if you do not need such a boon yourself, then you can give them to a loved one who does. Or you can sell them, of course.’

‘Sell them?’ The sick man was rather shocked.

The pardoner nodded earnestly. ‘They fetch high prices, especially in this day and age, when no one knows for certain whether the plague is really gone. People buy my tokens for protection.’

‘I see,’ said the sick man, nodding. Then he frowned. ‘Why do you have so many? Surely, their owners cannot have sold them to you? If folk have been to Jerusalem, Santiago or Rocamadour, they will want to keep these blessings for themselves.’

A distinctly furtive expression crossed the pardoner’s face. ‘Sometimes they need money to get home again, which I can provide. And sometimes the tokens just drop off their clothes when they hurl themselves in front of St Thomas’s tomb. I usually look around at night, when the cathedral is quiet, and I am often lucky.’

The sick man stepped back when his travelling companions descended on the stall, clucking and cooing over the merchandise. Several made purchases, and he was staggered by the amount of money that exchanged hands. The pardoner was right: his was a lucrative business. And if the badges really were holy, then perhaps they would work miracles, too. For the first time since the onset of his disease, the sick man felt the stirrings of hope.

Surreptitiously, he looked at the scallop shell he had palmed while the pardoner had been talking. He did not feel as though he was about to be struck down for stealing it. Indeed, he had the sense that it was better off with him than with a villain who would hawk it for silver. Could it cure him? It had not eased his symptoms as far as he could tell, but perhaps it would take more than one badge to combat the disease that was eating him from the inside out. He needed more – as many as he could get. Smiling to himself, he eased into the shadows and began to make his plans.

January 1358, Cambridge

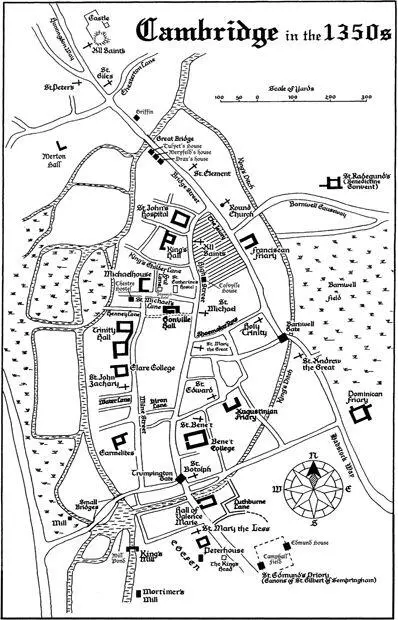

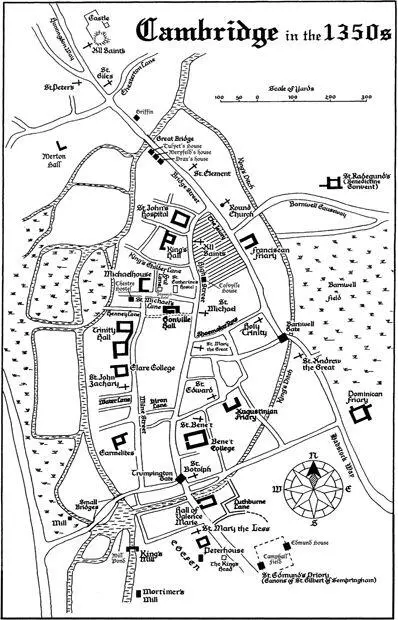

There was a fringe of ice along the edge of the River Cam, and its brown, swirling waters, swollen with recent rain, looked cold and dangerous in the grey light of pre-dawn. Frost speckled the rushes in the shallows, and John Jolye wondered whether it would snow again. He hoped so. The soft white blanket that had enveloped the town the previous week had been tremendous fun, and he and his friends from the College of Trinity Hall had spent a wonderful afternoon careening down Castle Hill on planks of wood.

Читать дальше