Susanna Gregory

MYSTERY IN THE MINSTER

2011

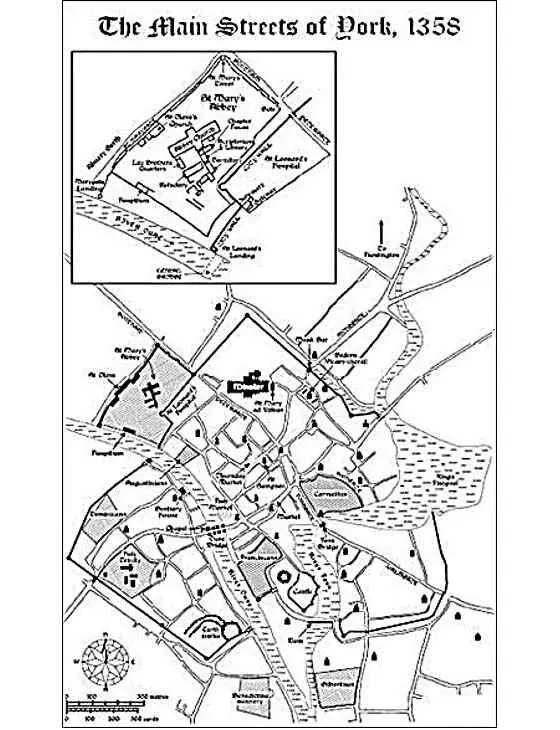

The Archbishop’s Palace, Cawood, near York,

19 July 1352

William Zouche was dying. He had been unwell before the plague had swept across the country three years before, and had been sorry that the disease should have spared him, a sick man weary from a life of conflict and tangled politics, but had snatched away younger, more righteous souls.

He was not afraid to die, although he was worried about how his sins would be weighed. He had tried to live a godly life, and had been a faithful servant of the King, even fighting a battle on his behalf and helping to win a great victory over the Scots at Neville’s Cross. It was hardly seemly for an Archbishop of York to indulge in warfare, though, and he regretted his part in the slaughter now, just as he regretted some of the other things he had done in the name of political expediency.

He was particularly sorry for some of the exploits undertaken by two of his henchmen, although he knew they had been necessary to ensure the smooth running of his diocese. But would God see it that way, or would He point out that the same end could have been achieved more honestly or gently?

Opening his eyes, Zouche saw his bedchamber was full of people – officials from his minster, representatives from the Crown, chaplains, town worthies, members of his family and servants – all waiting for the old order to finish so they could turn their attention to the new. He was simultaneously saddened and gratified to see a number in tears. For all his faults, he was popular, and many were friends as well as colleagues, kin and subordinates.

His gaze lit on his henchmen – clever Myton the merchant, weeping openly and not caring who saw his grief, and dear, devoted Langelee, keeping his emotions in check by staring fixedly at the ceiling. Seeing them turned Zouche’s mind again to his sins, and the time his soul might have to spend in Purgatory. It was a concern that had been with him ever since the horror of Neville’s Cross, so he had started to build himself a chantry chapel in the minster, where daily prayers could be said for him – prayers that would shorten his ordeal in the purging fires, and speed him towards Heaven.

‘You will see it is completed?’ he asked his executors, the nine men he had appointed to ensure his last wishes were carried out. He loved them all, and had been generous to them in the past with gifts of money, privileges and promotion. He trusted them to do what he wanted, but his chapel was important enough to him that he needed to hear their assurances once again.

‘Of course,’ replied his brother Roger gently. ‘None of us will rest until your chantry is ready.’

‘And you will see me buried there? You will put me in the nave for the time being, but when my chapel is completed, you will move my bones into it?’

They nodded, several turning away, not wanting him to see their distress at this bald reminder of his mortality. Reassured, Zouche leaned back against the pillows. Now he could die in peace.

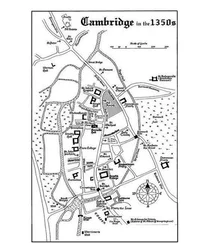

Cambridge, March 1358

It had been an unpleasantly hectic term for the scholars of Michaelhouse. As usual, the College was desperately short of funds, so the Master had enrolled additional students in order to charge them fees. The strategy had been a disaster. Their presence meant classes were larger than his Fellows could realistically teach, and the extra money soon disappeared, leaving more mouths to feed but scant resources with which to do it. So when the bell sounded to announce the end of the last lesson before Easter, and the students clattered out of the hall to ready themselves for their journeys home, all the Fellows heaved a heartfelt sigh of relief.

‘Thank God!’ breathed John Radeford as he entered the conclave, the one room in the College where Fellows could escape from their youthful charges – not that there had been much opportunity to use it of late. He was a handsome, neatly bearded man of medium height who taught law. ‘I do not think I could have endured another day! Had I known you worked this hard, I would never have enrolled in Michaelhouse last month.’

‘It has been difficult,’ agreed Brother Michael, a portly Benedictine theologian who was also the University’s Senior Proctor. He was sprawled in one of the fireside chairs, uncharacteristically dishevelled. ‘And the gloomy weather has not helped – we have not seen the sun in weeks.’

‘Mud and drizzle,’ nodded Father William. He was a grubby, opinionated Franciscan of dubious academic ability. His students often complained that they knew more about their subject than he did, but he was blessed with an arrogant confidence equal to none, and rarely allowed their criticism to trouble him.

‘I am worried about Bartholomew,’ said Radeford, pouring himself a cup of the College’s sour wine and sinking wearily on to a bench. ‘He has vast numbers of patients to see, as well as teaching our medical students. It is too much, and he looked ill this morning.’

‘One was waiting for a consultation the moment teaching was over.’ Michael’s plump face creased in concern: Bartholomew was his closest friend, and Radeford was not the only one who had noticed the toll the physician’s responsibilities were taking. ‘He did not even have time for a restorative cup of claret before he left – not that this vile brew would have revived his spirits.’

‘The pressure will ease now term is over,’ said William soothingly. ‘Incidentally, I am going to adjust the marks of a few of my lads, so they graduate early. It will lighten my burden considerably, and thus save me from an early grave. I recommend you do the same.’

‘That would be unethical, Father,’ said Radeford sharply. ‘We have a moral obligation to–’

He was interrupted when the door flew open, and the College’s Master entered. Ralph de Langelee looked more like the warrior he had once been than a philosopher, with his barrel chest and brawny arms. He was not a good scholar, having scant interest in the subjects he was supposed to teach, and his colleagues often wondered why he had not stuck to soldiering. But he was an able administrator, and even his most vocal detractors acknowledged that his rule was diligent and fair.

‘I have just received a letter,’ he announced, anger tight in his voice. ‘From York.’

‘From your former employer?’ asked William politely. ‘The Archbishop?’

Michael and Radeford exchanged an uneasy glance. They knew from the stories Langelee had told them that he had engaged in all manner of dubious activities on the prelate’s behalf – bullying enemies, delivering bribes, acquiring properties for the minster by devious means. There had also been hints of even darker deeds, but he had not elaborated and they had not asked, feeling it might be wiser to remain in ignorance. Thus neither was comfortable with the fact that such a man should have contacted their Master now.

‘He is dead.’ An expression of great sadness flooded Langelee’s blunt features. ‘I wish he were not – he was a good man.’

‘Is that why the letter was sent?’ asked Michael, struggling to hide his relief. ‘To inform you of John Thoresby’s demise?’

‘It is not about Thoresby,’ snapped Langelee. ‘He is hale and hearty, as far as I know. I was referring to William Zouche, who was Archbishop before him. He died almost six years ago now, but I still miss him – he was a friend, as well as the man who paid my wages. Thoresby hired me afterwards, but working for him was not the same at all.’

Читать дальше