He was hard pressed not to gape when it began to arrive, used as he was to the frugal fare of Michaelhouse. There was fresh fish, an impressive array of cheeses, several kinds of bread, stewed fruit and ale served in jugs large enough to be called buckets. The meal reflected the fact that the abbey was not only rich enough to buy whatever it chose, but that it was located in a city with access to the sea – goods were available both from the surrounding countryside and from overseas, which accounted for some of the more exotic wares provided.

‘If we eat like this every day, we shall go home the size of Michael,’ muttered Radeford to Bartholomew, as enough pottage was ladled into his bowl to feed a family for a week. He produced the silver spoon he always used at meals, being of the firm belief that horn ones were unhygienic. It was dirty from the last time he had eaten with it, so he wiped it on his cloak, a practice Bartholomew was sure negated any sanitary advantages the metal might have conferred.

‘I heard that,’ said the monk, offended. ‘I am not fat, I have heavy bones. It is a medical fact, as Matt will attest.’

Before Bartholomew could remark that it was not a medical fact recognised by any physicians, Abbot Multone, a short, bustling man with large white eyebrows, regarded them admonishingly.

‘We maintain silence during meals at St Mary’s.’

Thus rebuked, the only sounds for the rest of the repast were the clatter of cutlery on dishes and the mumble of a monk reading from the scriptures. Meals were supposed to be taken in silence in Michaelhouse, too, but scholars were a talkative crowd, and it was a rule they seldom followed.

‘Right,’ said Langelee, when the Abbot had intoned a final grace, signalling the end of the silence. ‘Now let us be about our business before we can be delayed any further.’

‘It is raining!’ exclaimed Michael in dismay as he stepped through the door. ‘How did that happen? The weather was glorious before we went inside.’

‘It is only a shower,’ said Langelee dismissively. ‘It will soon clear up.’

‘It will not,’ muttered Cynric, appearing at Bartholomew’s side and making the physician jump by whispering suddenly in his ear. He crossed himself as he squinted up at the sky. ‘Look at the blackness of those clouds, boy! It is an omen – something very bad will happen to us here.’

‘Nonsense,’ said Bartholomew, who rarely took his book-bearer’s predictions seriously. ‘Besides, I am going home in a few days whether we have secured Huntington or not – I will never catch up if we miss the beginning of term, and we cannot afford to leave Father William in charge for too long. So there will not be time for dire misfortunes to befall us.’

‘There will,’ insisted Cynric earnestly. ‘I can feel it in my bones.’

Bartholomew watched him walk away, and although the rational part of his mind dismissed the warning as a lot of superstitious drivel, there was something about the utter conviction in the Welshman’s words that left him with a distinct sense of unease.

Langelee and his Fellows had just reached the abbey’s main gate when a voice caught their attention. A monk was running towards them, waving frantically. He was a short man, with bright eyes and a narrow head that gave him the appearance of an inquisitive hen.

‘Good. I caught you before you escaped. Come with me – Abbot Multone wants to see you.’

‘Why?’ asked Radeford anxiously. ‘Because if it is to berate us for chatting during breakfast, you can assure him it will not happen again. We are sorry.’

The monk grinned. ‘No, he just wants to meet you properly. I am Oustwyk, by the way, his steward. And if you want anything – anything at all – come to me first.’ He winked meaningfully.

‘Thank you,’ replied Michael. ‘Since you have offered, the edibles in your guest house–’

‘We call it the hospitium,’ interrupted Oustwyk. ‘We keep it for less exalted company, although I have always considered it far nicer than the draughty hall we use for wealthy visitors – the ones from whom we aim to wheedle benefactions.’

‘–in the hospitium are reasonably generous,’ Michael went on, blithely ignoring the subject of donations. Michaelhouse simply could not afford one. ‘But another jug of wine, a bowl of nuts and some pastries would not go amiss. For emergencies, you understand.’

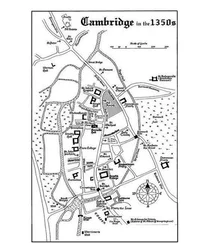

Oustwyk waved a dismissive hand. ‘The hosteller will see to that. I was offering other services. I know York better than anyone, and can get you anything you want.’ He glanced at the physician. ‘Such as a hat. People do not go hatless in York. It is not seemly.’

‘He lost it falling off his horse,’ explained Langelee.

Bartholomew winced. He was an appalling rider, and the journey had taken far longer than it should have done because of his inability to control even the most docile of nags. But he disliked his colleagues remarking on it to strangers, even so.

‘Hats, cloaks, shoes,’ said Oustwyk, waving an expansive hand. ‘Women. Or even information.’

‘We can find our own women, thank you,’ said Langelee indignantly. ‘I know–’

‘Information?’ interrupted Michael, speaking before the Master could say more than was politic. ‘In that case, you can tell us who they are.’

He pointed through the gate to the street, where a procession of thirty or so men in clerical robes was passing. All wore smart black cloaks that billowed impressively in the wind and matching hoods trimmed with white fur. They kept their elegant shoes from the filth of the street with wooden pattens, which made sharp clacking sounds on the cobbles.

‘The vicars-choral,’ replied Oustwyk. ‘They will have finished their prayers in the minster, and are now going shopping in Bootham – a street with excellent cobblers. The vicars like shoes.’

‘I see,’ said Michael, bemused by the confidence.

‘You will not have vicars-choral in Cambridge, so I shall tell you about them,’ Oustwyk went on, apparently unaware that Michaelhouse was a quasi-religious foundation, so its members needed no such explanation from him. ‘The minster has canons, appointed to perform various functions, but most of them live away, so they appoint deputies to do their duties. These are called vicars-choral.’

‘Three have broken ranks, and are coming towards us,’ remarked Michael.

Oustwyk nodded. ‘The fat, sly one is Sub-Chanter Ellis, their elected leader. The one who looks like an ape is Cave, his henchman. And the pretty one is Jafford, who is popular with whores.’

‘I beg your pardon?’ asked Michael, while Bartholomew thought Oustwyk’s descriptions were brutally accurate. Ellis was portly and his close-set eyes did make him appear devious; Cave had heavy brow-ridges and long arms that rendered him distinctly simian; while Jafford’s halo of golden curls and rosy cheeks would not have looked out of place on an angel.

‘Jafford has care of the Altar of Mary Magdalene,’ explained Oustwyk. ‘In the minster. And as whores feel that particular saint watches over them, they are always hovering around it. The Archbishop disapproves, but Dean Talerand says they have a right to pray there, and Jafford is always very accommodating.’

Before Michael could ask Oustwyk exactly what he was saying about Jafford’s relationship with the city’s prostitutes, the vicars arrived.

‘You must be the scholars from Cambridge,’ said Ellis, with a distinct lack of friendliness. He had fat, red lips, which glistened with saliva. ‘We have been expecting you.’

‘Remember me, Ellis?’ asked Langelee, lifting his hat to reveal his face.

The sub-chanter gaped in astonishment. ‘Langelee? Good God! I know Cambridge is well behind Oxford in academic standing, but I did not imagine it had fallen low enough to admit you!’

Читать дальше