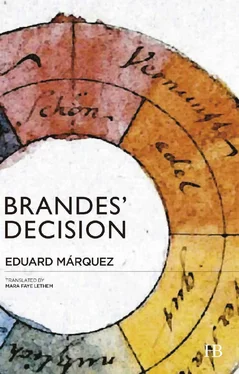

Eduard Márquez - Brandes's Decision

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Eduard Márquez - Brandes's Decision» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Hispabooks, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Brandes's Decision

- Автор:

- Издательство:Hispabooks

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Brandes's Decision: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Brandes's Decision»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Brandes's Decision — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Brandes's Decision», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It would be perfect if life were as easy to correct as a drawing. Perhaps we’d miss out on valuable lessons if we made fewer errors, but it would be a good way to save ourselves headaches. Despite everything, I’d like to remember Erika without reproaching myself for all the things I didn’t say or do when I should have, and without being angry with her for the pain she caused me. Perhaps then I could recover the good moments without tarnishing them with hatred. But it’s too difficult for me. Especially when I think about Konrad. I imagine that without him everything would have been simpler. We would have just been two people at odds, unable to understand each other, and we could have resolved it fairly easily, but shortly after Konrad was born, looking into his eyes for the first time, I discovered that the ties that bound me to him were too strong and inexorable.

Everyone said that he looked like me. My father was even convinced that he had a resemblance to my mother. I never saw it, but I didn’t argue with him. As a boy, Konrad was curiosity incarnate. He rummaged through everything. He would open up drawers and empty them. Or pull books off their shelves. Even still, I enjoyed bringing him to my studio. Sometimes he would stare at the paintings with a serious expression, as if he were a critic about to give his assessment. But his favorite form of entertainment was the zoetrope. Watching it spin, he would shriek and laugh like crazy. “More ‘tozotope,’ more ‘tozotope,’” he would say over and over as he imitated the sheep jumping over the wooden fence. He also loved to muck up in the paints, especially if he could mix them with the sand from the courtyard and dirty himself up to the elbows. And he adored dogs, but Erika never let him have one. She was afraid of them, even though she wouldn’t admit it. At night, after reading him one of his favorite stories, like The Wolf and the Seven Young Kids or The Elves and the Shoemaker , or when I came home late and he was already sound asleep, I would sit on his bed and just look at him. Hearing his breathing, free from worries and suspicions, calmed me.

I so wish he were here. Not only would I not have to die alone, but maybe he would be curious about my stories, and I could tell him about my memories of his grandparents, and Alma, or Sergeant Forkel and Professor Müller and, that way, my life wouldn’t completely slip through the cracks into oblivion. It’s a consolation like any other. I often try to imagine what he would look like if he hadn’t died, but the passage of time doesn’t make that easy for me. It’s become harder and harder to conjure up his image. But that’s how memory works. It’s a mystery. I can’t understand why it clings to memories that, given the choice, I would forget in the blink of an eye and yet doesn’t allow me to retain others, ones I would give anything to keep close.

Of course, Hofer didn’t forget about me. On his next visit, he left the soldiers downstairs and came up on his own. Since I saw his car entering the alley, I had enough time to hide the watercolor I was working on. Without a word, Hofer planted himself in front of the Cranach again.“So, have you made your decision yet?” he asked. “No,” I replied. “Not yet. It’s that. .” “Well, Göring is tired of waiting,” he interrupted. “And so am I.” Then he turned slowly to pierce me with his gaze.“I don’t suppose you’re thinking about trying to trick me, right?” I wanted to say yes, and that I was fed up too, of all of it, but sometimes, as my father would have said,“what’s kept quiet is worth more than what’s said.” I shook my head. Hofer smiled with satisfaction. “That’s a good boy.” Then he came over and gave me a couple of pats on the arm.“Since you are having such a hard time deciding, I’ll do it for you. Tomorrow I’ll come for the Cranach and I’ll give you back all your junk. How does that sound?” he added. Without waiting for a reply, he backed up towards the door he had left open.“Until tomorrow.” Also two words. Like “You decide,” but more forceful, with the weight of his threat spreading through the studio like a cloud of poison gas.

Even though I was nearly done, knowing that I had to finish that night was upsetting, because I never could stand being rushed. But, at the same time, I was calmed by the idea that I was only a few hours from the end. Like so many other times, the first light of day found me working, my back aching and my eyes red, but feeling the pleasant weariness that comes with finishing a job. If I had been living in Hauterive at that time, it would have been the moment to take a good long walk to shake off the stiffness and whet my appetite for wolfing down one of Alma’s lavish breakfasts. That’s why it was my favorite place to work. Because there is nothing like a landscape in the early dawn, with all its colors just about to burst forth again, to recover from a night of work. And it was the only workspace I tailored to my needs. When I happened upon that mill on the outskirts of town, I didn’t think twice. I had been searching high and low, and I’d almost given up on finding the perfect place. Isolated, but close enough to Paris to be able to go there whenever I wanted. With lots of trees. And a river. And enough space to build a studio away from the house, taking advantage of a clearing in the forest. Paul Nelson, whom I met thanks to Braque, took on the project, a mix of greenhouse and woodcutter’s cabin. Alma was taken with the place from her first stay there, shortly after we met. She was happy taking long walks and caring for the garden. She could spend hours there. I liked to watch her work, focused on her tinkering like a scientist puttering over test tubes.

Alma wasn’t particularly pretty. She had very hard, sharp features, with sunken eyes and a slightly large mouth, but her beauty came, when least expected, from the small details. From the way she pushed her hair out of her face; from the subtle shift — as if she weren’t entirely convinced — from smile to laugh; from the way she wrinkled her nose in distaste; from her voice with its many registers and tones; from the movement of her hands, which she used to reach those places she couldn’t reach with words. I think she would have made a good model, but she never let me try. She didn’t want me to paint her portrait. She couldn’t bear the thought. All I have left are some photographs. And that recording of The Human Voice where, at one point, she complains about the distance that separates her from her absent lover. When I hear it, I have to struggle not to think about the years without her, maybe not entirely extraneous years but definitely ones lived without much conviction.

Alma occupies the blue vertex of the chromatic star because that’s the color of breathable air, but I still don’t know how to distribute the other colors. Maybe there’s no need. I suppose that green is for the trenches. And yellow for my parents, but I’m not sure about that, because maybe it would only be my mother’s color.

If I had to choose one moment with Alma to place in her vertex, I would opt for a dusk we spent together at Hauterive. Sitting in the garden, in silence. Alma watering. The sun low. The murmuring of the river. The gleam of the leaves. The aroma of the damp earth. For a few moments I had the sensation — as potent as it was naive — that nothing could separate us. That I had lost my parents and Konrad but that, finally, after a long wait, someone had come to fill that void. Alma must have noticed that I was looking at her, because she turned. And smiled. That’s all. Then she continued watering. I never felt so close to anyone as I did to her then.

My father said more or less the same about my mother. Although sometimes, when he divulged one of his rare confessions, I was flustered. For a while the fact that he had loved her so much even made me feel a little jealous. But later, when I realized that what he felt for my mother was no threat to me, I was more surprised that such a serious, circumspect man had ever behaved — as he occasionally described it—“like an impetuous lovesick boy.”“I would have done anything for her,” he told me more than once. Now I know that those two behaviors aren’t mutually exclusive. And, in fact, he was the same way about his work. The rational, methodical scientist coexisted with the juggler of stories. When he got excited, he was unpredictable. He could jump from reagents or the chemical structure of any element to the rooster eggs hatched by toads to create basilisks, whose ashes, when mixed with red copper, the blood of a redhead, and vinegar, made what’s called Spanish gold. Or that’s what a Benedictine monk he once told me about had said. At an age when I barely understood how children were born, I was as surprised to hear that roosters could lay eggs as I was by the lethal gaze of the basilisks, and I drove him crazy asking for the only animal that could protect me from it. “How can we have a weasel in the house?” he would ask me when at night, drawn by my shrieks, he lay down in my bed to calm me.“I don’t know,” I would answer,“but I’m really scared.” Finally I was so annoying about it that, instead of a weasel, he gave me a little hand mirror and, after repeating ad infinitum that, if necessary, it would work to kill the basilisk with the reflection of his own gaze, he managed to get me to sleep soundly without nightmares. For a long time I carried it in my pocket at all times and, before getting into bed, I had to check several times to make sure it was under my pillow.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Brandes's Decision»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Brandes's Decision» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Brandes's Decision» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.