IN THE SPRING OF 2000, after my mother passed away, I gave myself entirely to my studies. The logic of mathematics — its methods of induction and deduction, its power to describe abstract shapes that have no counterpart in the real world — sustained me. I moved out of the apartment that my mother had been renting ever since she and Ba first came to Canada, and in which I had grown up. Desperate to leave it behind, I cobbled together every penny I had and bought a dilapidated apartment on Alexander Street. The windows looked straight out into the port of Vancouver and, at night, the endless arrivals and departures of multi-coloured shipping containers, what they held, what they divulged, comforted me.

I kept my parents’ papers in the bedroom closet and a Cantor quote taped to the wall: “The essence of mathematics lies in its freedom,” and, like a child, I distracted myself by imagining numbers so immense, so limitless, they far exceeded all the atoms in the universe. Numbers, real and imaginary, were a language inside me, equations were branchings of substance and shadow, relationships and interrelationships, randomness and pattern, the fractional, incomplete yet consistently ordered world we live in. I listened to my father’s records but thought only of intervals, frequency and temperament, of the expression of numbers in an audible world.

By the time I turned twenty-five I had finished my Ph.D. and, thanks to a well-received paper I had published in Inventiones Mathematicae , I was offered teaching positions in Canada, the United States, Korea and Germany. To the surprise of my professors, I chose to stay in Vancouver. A year later, I was teaching Galois theory, calculus and number theory, as well as a seminar on the symmetry and combinatorial structure of Bach’s Goldberg Variations . I had a small, but close, circle of friends. In and out of my research time, I continued to be preoccupied by Ma’s death and by the statistical improbability of finding Ai-ming. My mind was full of numbers; I was not lonely.

Yet I understood, even then, that my life was strange, shaped by questions that seemed to have multiple and conflicting answers.

—

In 2006, the year I turned twenty-seven, I made my first visit to Hong Kong.

For the next ten days, I disappeared into the crowds, nightclubs and bars of Mong Kok, returning to my rented room at 7 a.m. and sleeping until mid-afternoon. Ever since Ma’s death, work had been my entire existence; I had become, without knowing it, the perfect caricature of a reclusive professor, or as G.H. Hardy described mathematics, “the most austere and the most remote.” In the concentrated work of trying to prove a theorem, social life fell by the wayside. But, here, in Hong Kong’s neon lights and perpetual noise, I let myself be someone else entirely. Walking home as the city woke, miles from sober, I felt happy for the first time in many years.

Finally, the day before I was due to fly home, I willed myself to find the dwelling in which Ba had been living — the last one, since he had moved several times during the final months of his life. The address, 9F, Alhambra Building, 202 San Tin Dei, was known to me from police and coroner reports, which concluded: “The deceased, Jiang Kai, burdened by gambling debts, suffering from acute depression, committed suicide by jumping from his ninth-floor window.”

Sixteen years later, the building was still there, and I wondered how much it had changed, if at all, since 1989. There was no lobby, there was not even a door, just a grey staircase that led up from the street. I went up, passing room after room; metal grates or small altars, offering oranges to the ancestors, were all that separated each dwelling from the stairwell. The apartments were minuscule, with barely enough space for a bed. I saw windows the size of a sheet of paper. I climbed higher and higher. The door to 9F was closed and though I stood before it for a full half hour, I could not bring myself to knock. I had an irrational fear that Ba would open the door, that I would face the window he had climbed through. I turned around and descended. After leaving the building, I took a taxi to the district office of the Hong Kong Police where I requested a copy of my father’s file. An officer helped me fill out an application for access to information, telling me that I would receive a reply, by post, within thirty days. I left the police station and wandered aimlessly. Standing on an overpass that crossed a six-lane thoroughfare, and despite the noise of traffic and the vibration of the entire structure, I could hear nothing. My life felt entirely out of order.

I took the subway almost all the way to the Chinese border, switched to a bus and then walked up a paved road. My father’s only request had been to be buried at this cemetery, a place whose name brings together the characters 和 (harmony) and 合 (to close, to be reunited). But I did not know, and had never known, exactly where his ashes lay. In the cemetery office, I was surprised to find they had no record of him at all. The young man at the desk asked, bored but apologetic, if it was possible that my mother had scattered his ashes in the Garden of Remembrance. “It’s possible,” I said. “She never told me.” The man returned to his paperwork and I went outside. All the graves were set on narrow terraces, rising upwards along concrete steps. After walking for several hours in the heat, I was drenched in sweat and could barely see. Crickets cried unceasingly and the butterflies were delicate yet large as handkerchiefs. Above me, cotton balls that seemed to come from nowhere glided through the air.

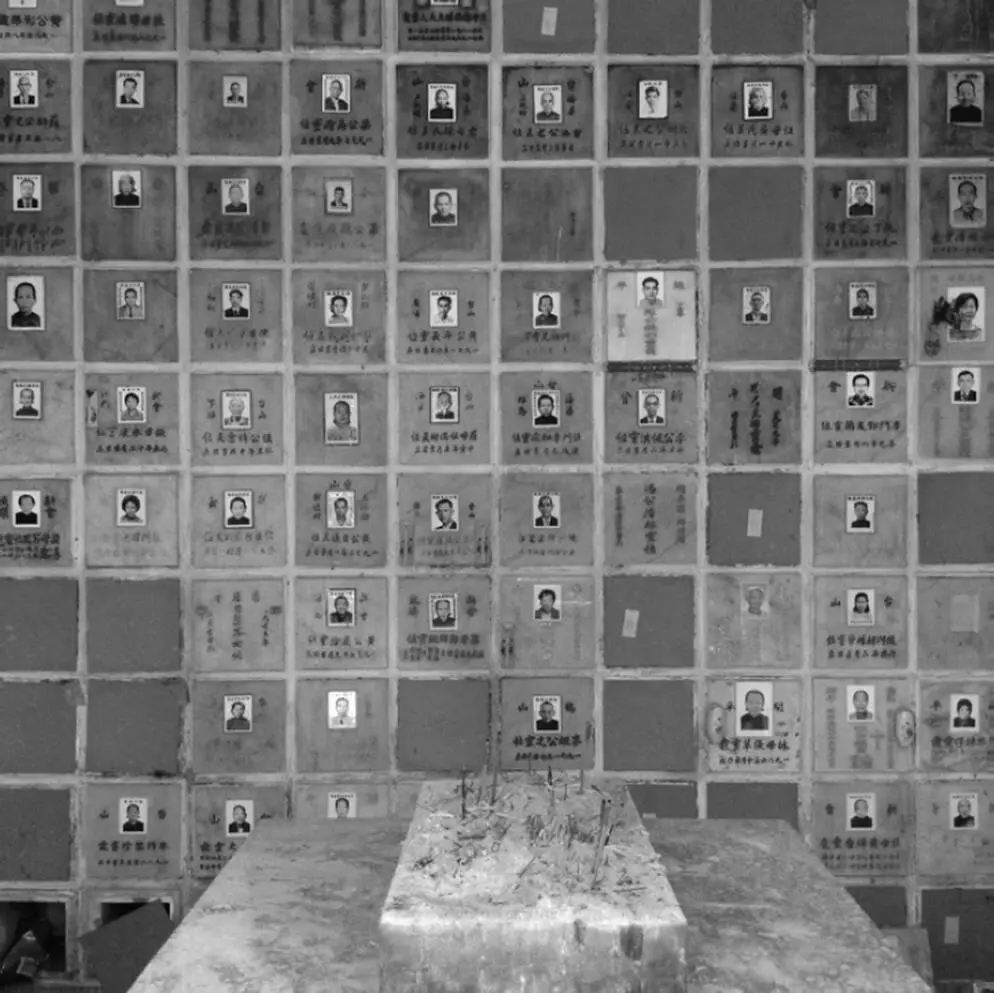

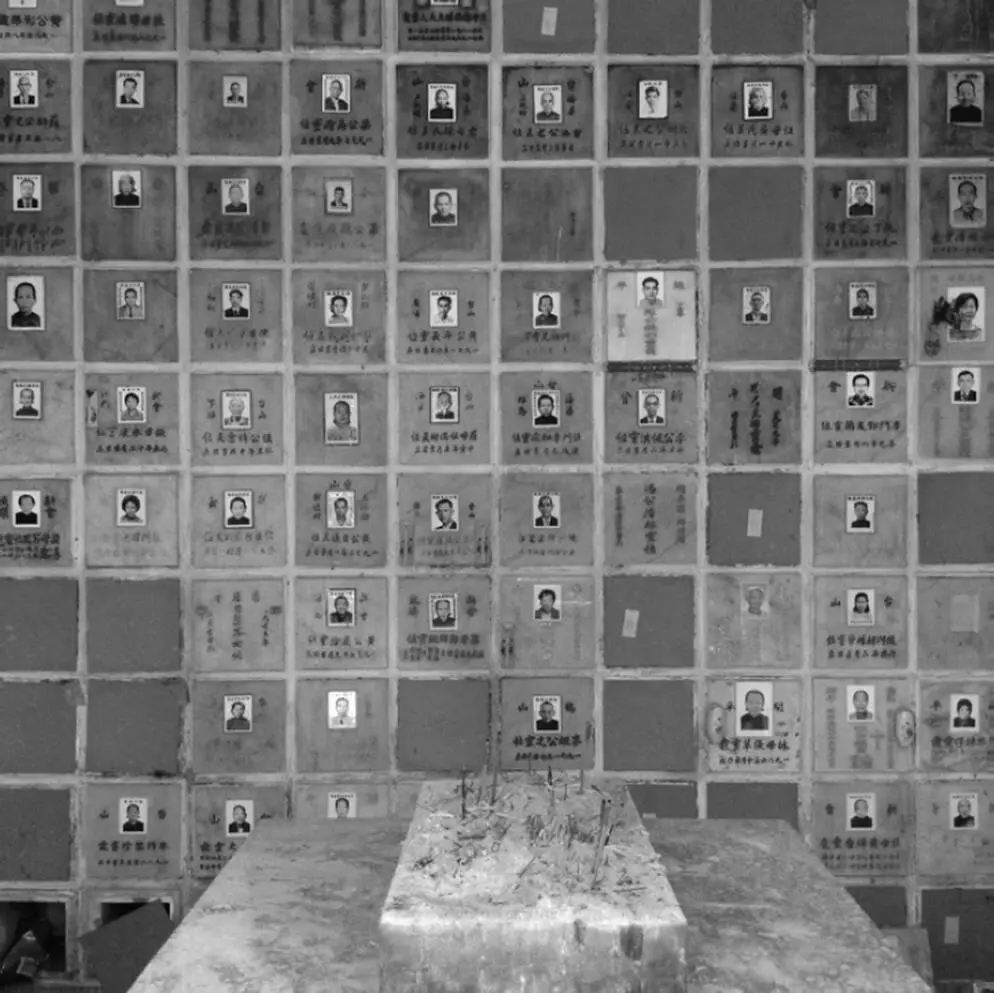

I came by chance to a small columbarium where, inside, four tiny tea cups and four pairs of red chopsticks lay waiting on a sheet of newspaper. Square niches, for holding urns and ashes, were mounted on the walls. But some squares were empty: these had only cardboard covers with two characters written in red marker, 吉 (fortunate) and 玉 (jade). What this meant, I could not fathom. The room was soft with spiderwebs, and the teacups and chopsticks appeared to have been left behind by ghosts. Desperate to find him, but afraid, too, I studied all the pictures one by one. His picture was not there. I left the columbarium and walked between the graves, but still Ba could not be found. At last I sat down on the steps of a long walkway. A worker, clothed in blue, passed by, with a white towel tucked into the collar of his uniform. He wanted to help but I could not communicate what it was that I wished for, and finally he left me where I was, under the sun, thinking of my parents.

Four weeks later, a small box arrived at my office at the university. Inside were a number of documents, police and autopsy reports, some of which my mother had already received. There were a dozen photographs of my father’s body, his clothes and few possessions. There were also letters I had never seen before, eight from my mother, and five from Sparrow. One of Sparrow’s letters contained a composition, 31 pages long, the pages taped together: a sonata for piano and violin called The Sun Shines on the People’s Square . At the top, Sparrow had written: “For Jiang Kai.” The pages, copied by hand, were dated May 27, 1989. A one-page report stapled to it took me many minutes to decipher. Finally, I understood that these pages had been accidentally misfiled and the error had only come to light in 1997 during the digitization of all police files. Because so many years had passed and the file was now closed, they were releasing the original documents to me, the only surviving family member. I was looking at letters that even my mother had never seen — not when she went to Hong Kong to bury my father and not later on, when she, too, requested the file.

Читать дальше