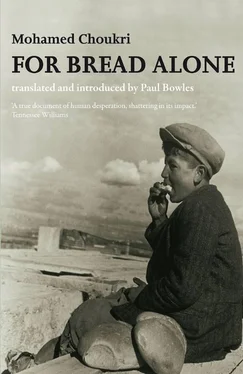

The odour was overpowering, unbearable. I peeled off the skin. Then with disgust, with great disgust, I began to chew it. A taste of decay, decay. I chew it and chew it but I can’t swallow it. I can’t.

From time to time the small sharp stones hurt the soles of my feet. They hurt. I went on chewing the fish as if it were a wad of gum. It was like chewing gum. I spat it out. Its stink was still in my mouth. I looked down with rage at the mass I had spat out. With rage. I ground it into the pavement with my bare feet. I stepped on it. I ground it under my feet. Now I chew on the emptiness in my mouth. I chew and chew. My insides are growling and bubbling. Growling and bubbling. I feel dizzy. Yellow water came up and filled my mouth and nostrils. I breathed deeply, deeply, and my head felt a little clearer. Sweat ran down my face. Running, running. I thought of the boy who had saved me from the police last night. Why didn’t he wake me up this morning? Why? Did he try, and couldn’t because I was sleeping so heavily? Perhaps he tried. I was sorry we had not given each other our names. I was sorry. The fisherman sat in his boat, eating his loaf of bread. He eats it, and I, I am eating it too as I watch. He leans over the gunwale, and I watch him wearily. I watch and watch, thinking that he may throw something away, something I can eat, as he is eating. The monkey tied to the mast seizes something, and nervously cracks it between its teeth. I hoped the fisherman was chewing without pleasure, the way I had chewed my rotten fish. I watched the loaf of bread avidly. He was gazing distractedly at the waterfront skyline, running his eyes vaguely over old Tangier. Throw away your bread now, the way I threw away my fish, I told him silently. He threw the bread into the water. A delicious taste of salt filled my mouth. Delicious. A feeling of pleasure revived my weak body. In spite of being so tired, I felt better. I stripped off my shirt and trousers, and plunged into the water. I swam beneath the bread and saw that the slab of meat that had been inside it had already sunk to the bottom. There goes half my luck, I thought. The fisherman began to laugh uproariously. I raised my head towards him, my hand clutching the bread. I looked at him and at the bitten piece of bread. Lumps of shit floated all around me in the water. Floating, floating. I squeezed the bread in my hand. It was spongy, and sticky with oil from the boats. That bear is laughing at me as though I were a big fish he was going to catch. He’s laughing at me. I’ve swum into his net. Inside. I began to swim towards the concrete steps, passing other small lumps of shit and bread bobbing in the water in front of my face, bobbing and bobbing. I pushed them away as I swam. In my mind they became connected: bread and shit. Connected. A little water went down my throat, went down. I choked, choked. There was pain in my head and chest. I climbed two of the steps. On the third step I slipped and rolled back down into the water. Again the water ran into my throat. Again. The idea came to me that I was going to go on for ever, climbing up the steps only to slip and fall back into the water. On and on. Even as I got to the highest step, I imagined myself falling backwards into the bay. Falling again. I was very careful where I placed my feet. My body was covered with sticky oil. I picked up my shirt and trousers, and started walking. On my way, I looked behind me and the fisherman waving at me. Laughing. The sound of the laughing dies away little by little. Dies away. Now he has stopped laughing. Stopped.

He called after me, wheedling. Hey, boy! Come here! It’s only a joke. Come on. Here’s another loaf of bread.

Poor kid, said the fisherman in the boat with him.

I did not turn around and go back towards them. The humiliation was very great. Too great. Ahead of me on the pavement there were some more small fish that had been trampled on. Trampled underfoot. I raised my face to the sky. It was more naked than the earth. More naked. The hot sun struck my face, struck it. I began to tremble with fatigue. I tremble and shake. I see a cat reclining comfortably in a shady corner. It looks at me half-asleep, with indifference. Indifferent. Its white and black belly rises and falls slowly, slowly. I picked up one of the small, dry fish. Dry. It had a worse stench than the first one. Worse than the first. I began to vomit yellow water again. That was what I wanted. I wanted it. I vomited and vomited, until only the sound came out. Only the sound, the tight sound of retching. That was what I wanted. I walked towards the beach, feeling empty, weak. Now and then it seemed that I was about to fall and not get up again. In order not to think about what had happened and what might be going to happen, I began to look back at the footsteps I was making in the sand. The waves broke over them shortly after I made them. I watched my footsteps and the waves. I threw my shirt and trousers down onto the sand and began to rub my body with seaweed and sand. I rub and rub. My hair is even stickier than my body. Stickier. I went on rubbing and rinsing until my skin was red, red. The skin on my body was still sticky with oil, but not so dirty as before.

In the afternoon, after wandering far and wide, I sat down on some steps opposite the railway station. I did not manage to carry any suitcases for the travellers who arrived. I failed. I did not dare approach them. One of the porters yelled into my face: Get back! Out of here! Go on! This was a good town until you all landed here like a swarm of locusts!

They swore at me, spat on me, and shoved me away. A muscular young man gave me a hard kick and chopped me on the back of my neck. But I was determined to stay there. I stayed there. Later I succeeded in persuading a European to let me carry his suitcase. It was heavy. As I was lifting it up to carry it, a big man grabbed me and began to swear at me. He managed to convince the traveller that he was more capable of carrying the bag than I was. Violently he yanked the handle out of my hand. Violently. The situation has not changed at all so far. When I was seven or eight years old I always dreamt about bread. And here I am at sixteen still dreaming about it. Am I going to go on dreaming about bread for ever? The cat on the fishermen’s pier was luckier than I. It can eat fish out of the gutter without vomiting. Yes, without vomiting. There’s nothing left but begging or stealing. But it seems to me that a beggar sixteen years old is not going to collect much. Yes, it is difficult. Sebtaoui was right: begging is a profession for children and old people. If a young man can’t find work, it’s more shameful to beg than to steal. That’s what he used to say. I wonder where they are now, he and Abdeslam. Who knows?

A young man sat down near me and took out a pack of black cigarettes. Do you smoke? he said. I turned my head and answered weakly: Yes.

What’s the matter with you? Are you sick?

No.

He came nearer and I took a cigarette from him. He lighted a match.

Thank you. Not now. Thanks.

He got up, saying: Wait for me. I’ll be back.

I smelled the cigarette. If I smoke it I’ll vomit again without vomiting anything. The same as at noon. I heard the sound of a plane flying overhead, and raised my eyes to the sky. The noise slowly grew fainter, and I did not see the plane. A feeling of sleepiness stole over me. I heard the young man talking. Here!

The cigarette had fallen from my hand. I must have slept. Yes, I’ve been asleep.

He was holding out half a loaf of bread stuffed with tinned sardines. I saw a bottle of wine in his hand. He took a small glass out of his pocket and filled it. When he had drunk, he refilled it.

Raising the glass to his lips he said: Where are you from?

I answered as I ate. I’m from the Rif. My family lives in Tetuan.

Читать дальше