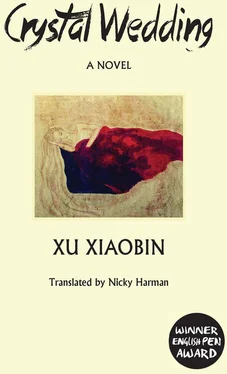

Xiaobin Xu - Crystal Wedding

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Xiaobin Xu - Crystal Wedding» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Balestier Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Crystal Wedding

- Автор:

- Издательство:Balestier Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Crystal Wedding: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Crystal Wedding»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Crystal Wedding — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Crystal Wedding», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

No matter. Tianyi could put up with the slights, because she was in love, wholly and completely in love — with the mysterious H Z.

12

The Tree of Knowledge won a major prize at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival. Karlovy Vary was a town in the south of the Czech Republic. Ten years later, Tianyi was lucky enough to visit it, and it took her breath away. It was as pretty as a child’s picture book. It was autumn and the entire city was gilded by autumnal foliage that blazed and shimmered in the breeze. A building in the distance looked like it had been built from a child’s wooden bricks. Near that building, she found and bought a set of gilded crystal wine glasses.

At the time of the festival, however, she knew nothing of Karlovy Vary. Though she had heard its name, she did not have a clue as to where it was and even had a vague idea it was in Africa.

The Tree of Knowledge was only shown in China after it had won the prize. On the opening night, the deputy director had a number of complimentary tickets, and the first person she thought to invite was her H Z.

There was no real mystery about who H Z was, it was just her abbreviation for Hua Zheng. In Tianyi’s eyes Zheng was a beautiful and dangerous man, especially beautiful precisely because he was dangerous. She first met him at the beginning of the 1980s, in the house of a friend. He was a formidable figure back then, with eyes that blazed so bright you could not see the pupils. Her friend Peng introduced them, saying with a laugh: ‘Tianyi, we all know you writers are fascinated by Che Guevara. Well, here he is in a modern guise. Have a good talk.’ Peng was given to hyperbole, but this time he was not exaggerating. Zheng and Tianyi hit it off straightaway and talked non-stop for seven hours. Peng had to bustle around and do the dinner without any help from them, but he did not grumble. He provided a good spread too: scrambled eggs, stir-fried cabbage, a dish of potato, aubergine and green pepper, stir-fried shredded pork, beancurd and mushroom casserole, and a sour and hot soup. But even eating could not stop the chatterers’ mouths, as Zheng and Tianyi talked on and on. Tianyi discovered that this lovable, boyish man liked nothing better than a good argument. He could not seem to help it: if you said east, he said west, and if you agreed west, he immediately changed his mind to south. Tianyi felt he was being argumentative for the sake of it, but Zheng defended himself: ‘A lot of the time, I try and start an argument because, when people argue, it livens up their thought processes.’

Tianyi heard it from Zheng first: ‘Mao Zedong is not a Marxist, he’s a peasant revolutionary imbued with a feudal king’s thinking.’ At the beginning of the 1980s, this was a risky thing to say, but to Tianyi’s surprise, she realized that these words clarified her innermost feelings.

‘I think that China’s biggest problems are, one, that there’s no religious faith and, two, our links to the finest things in our national culture have been severed. We’ve lost our traditions, so even though our economy may flourish, at a spiritual level I can see us becoming impoverished and degraded,’ Tianyi said despondently.

‘Most of the world’s rulers impose their rule by means of religious faith,’ Zheng replied. ‘But China is a country whose religions, Confucianism, Buddhism, Daoism, have all been smashed. Even Maoism has been smashed!…There are no standards, no bottom line, so value judgments are confused. Glass gets treated as diamond, vermicelli as shark’s fin. It’s really terrible!

‘When the Qing dynasty was overthrown,’ he went on, ‘old-style scholars spent a lot of the time debating which was the best for China: a monarchy, a constitutional monarchy or a republic. Actually, during the Republican years, a number of educated reformers did emerge but it’s true to say that for the last one hundred years, we have not only not gone forward, we’ve gone backwards. For instance, did you know that there was actually a legislative assembly at the beginning of the Republic? So I feel that after these latest economic reforms, we need corresponding political reforms, otherwise the consequences will be unthinkable.’

‘I like the Song dynasty,’ Tianyi suddenly said.

‘Why?’ Zheng, brought up short in the middle of his tirade, looked hard at Tianyi. Before him was a woman who might have stepped out of an ancient painting; she had a dignified, cultured air and, he was coming to realize, a rare purity of heart. He was captivated. Making an effort to cover his emotion, he asked: ‘Is that because intellectuals enjoyed a high status under the Song? I agree. I especially like the injunction of the Song philosopher, Zhang Zai, to intellectuals, “To establish the spirit of Heaven and Earth, and a good life for ordinary people” …’

‘… “To protect and perpetuate bygone wisdom, and maintain the whole world in peace forever”,’ Tianyi finished off for him. They fell silent and stared at each other. There was an instantaneous vivid flash of delighted surprise, of mutual recognition. Then each of them hurriedly looked away.

Tianyi decided she liked Zheng very much indeed. Oddly enough, her liking was entirely platonic. She felt no physical desire for him, still less any desire to use him. She felt about him the way she might feel about a heavenly emissary, or a sage. From their very first meeting, she did not treat Zheng as an ordinary man. And that was the root of the problem, because Zheng fell in love with her at their first meeting, even though she was four years older than him. Not that that put him off. He said to Peng: ‘Jenny von Westphalen was four years older than Marx.’ Peng did not repeat this remark to Tianyi straightaway, for one simple reason: he was in love with her himself.

One day, Tianyi suddenly said: ‘Zheng, I don’t think you’re cut out for politics.’

‘Why not?’ he asked, startled.

‘It’s simple, you’re not a politician. You’re an idealist. Born in the wrong age.’ Then she added (and Zheng would remember her words for the rest of his life): ‘You’re the ultimate idealist.’

Because of her feelings for Zheng, Tianyi was constantly dreaming up pretexts to spend time at Peng’s. It was the same with Zheng. So they regularly bumped into each other there, and chatted, cooked a meal, worked. Peng’s dad was the boss of some big company and had quite a bit of money put by. The family owned a two-courtyard home, and Peng’s father gave it to his son, thus making Peng one of the very few young people who owned their house at the beginning of the 1980s. It was a wonderful place for his friends to gather.

Over time, increasing numbers dropped by, and they dreamed up more exciting things to do. Often, they went to the Miyun Reservoir outside Beijing. They were so young then, Tianyi reflected. Nowadays, it was a long journey, two hours or more. Back then, it was much simpler, they just got on their rickety old bikes and pedalled there, talking and laughing.

They usually got to the Miyun Reservoir towards evening. They would start with a swim, then gather under some nearby trees and have their picnic. There were always plenty of provisions, though of course ‘plenty’ in those days only meant soy-stewed beef, coarse-grained bread and snacks, and a variety of pickles: sweet-soy ‘eight treasure’ vegetables, Korean chillis, home-made pickles, mouli in soy-paste, and so on. And salads and fruit, of course. Tianyi usually decided on what salads to bring, and she and Zheng made them up together. They made the mayonnaise for the salad in the most basic way. There was a bowl of peanut oil, heated up then left to cool; the oil was slowly added to the egg yolks — it had to be added a drop at a time, just a little bit too much and it curdled. That was the key to making mayonnaise, the adding of the oil at the beginning. At this crucial moment, the person in charge often added the oil too fast, curdled the mixture and had to be rescued by Tianyi. She always added the first few drops personally. When the mixture had begun to thicken, and the salt, sugar and vinegar had been added, then Zheng took over. He beat the mayonnaise with vigour, and a single-minded concentration that was comical and still raised a smile with Tianyi all these years later.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Crystal Wedding»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Crystal Wedding» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Crystal Wedding» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.