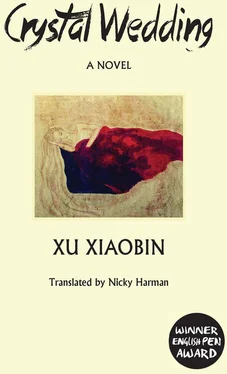

Xiaobin Xu - Crystal Wedding

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Xiaobin Xu - Crystal Wedding» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Balestier Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Crystal Wedding

- Автор:

- Издательство:Balestier Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Crystal Wedding: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Crystal Wedding»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Crystal Wedding — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Crystal Wedding», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

As a small girl, Tianyi loved copying pictures of pretty ladies from these children’s books, in fact she filled a whole notebook with her drawings. She copied the ‘Parrot Girl’ from a calendar they had too, a girl dressed in ancient costume, smiling and holding a fan with a parrot perch on a circular stand behind her. Mrs Feng, who ran the local library saw Tianyi’s efforts, and liked them so much she offered to teach Tianyi to paint. Mrs Feng made traditional costume dolls and was somewhat reclusive, so when she offered to take on Tianyi as her pupil, the news swiftly spread through their compound. Tianyi instantly became known as their ‘little artist’.

These picture books, with their cast of female characters, passionate, tender or staunchly heroic, imperceptibly stole into Tianyi’s young heart, so when she opened the first volume of The Story of the Stone , she immediately recognized the hero and heroine, Baoyu and Daiyu, picking them out from among dozens of other characters. She chose the bits in the book that were about their love story, reading obsessively through the dark hours of the night, until finally she read herself into a state of complete mental exhaustion. Night after night, she went without sleep, going to school the next morning feeling unwell, her eyes and face puffy. Back then, Di used to drop by so that they could go to school together, and one day she found the book lying by her bedside. She read the first line: ‘The author had a dream and spake …’ ‘Oh!’ Di cried, ‘So the author of The Story of the Stone ’s called “Spake”’. Scornfully, Tianyi said: ‘Whatever do you mean, “Spake”? “Spake is the past of to speak! How could you get to third grade without knowing that the author of The Story of the Stone was Cao Xueqin?’ Di, an unsophisticated girl, had always looked up to Tianyi, and now admiration turned into hero-worship. She put Tianyi on a pedestal, deferring to her in everything. There was no one to beat her friend, in her view, for knowledge, bravery, intelligence and good looks.

But too much living in fantasyland can take its toll on a little girl’s mental health, and Tianyi actually became delusional. She was put to bed, but even then, when no adult was watching her, she would sneak her copy of The Story of the Stone from under her pillow, and carry on reading. She got to Chapter 97, where Lin Daiyu burns her poems to signal the end of her heart’s folly and Xue Baochai leaves home to take part in a solemn rite.’ In her mind’s eye, she saw Daiyu, the hapless heroine, ashen pale, vomiting a stream of blood. Tears poured down Tianyi’s face like a tap that someone had forgotten to shut off, drenching the pillow cover, as she read Daiyu’s deathbed exhortations to her maid Nightingale. Increasingly self-pitying and troubled, she became convinced she was the dying girl. She was sleeping no more than a couple of hours a night, and her father became desperate to find medical treatment for her. Nothing worked however, and his darling daughter was becoming thinner before his very eyes. But the grim Reaper was not ready for her yet. One day, her paternal grandfather turned up.

Her grandfather still lived in the old family home in Shayang county, Hubei province. He was no ordinary granddad, having joined the Northern warlords and risen to a high rank in his youth. He had three sons and a daughter, but had passed down his love of military matters only to his eldest son, Tianyi’s Uncle Huairen, and not at all to her father or the youngest son.

Tianyi’s military uncle was a source of pride for the whole family, especially the children. Ever since she was a tiny child, Tianyi had known that she had an uncle in the People’s Liberation Army. All the kids wanted to visit him. He had a big house and a car, and a fancy cooker that good things were cooked on. Anything they asked for, they were given. Tianyi had been a greedy child — her maternal grandmother always said she was reincarnated from someone who had died of starvation. Whenever she got to her uncle’s house and smelled the cooking smells, her stomach would rumble. During the Starvation Years, between 1958 and 1961, Tianyi was especially keen to go and see him. The family and their neighbours in the large compound seemed to live in another world. They had no need to go digging up bitter greens or collect fungi to fill their baskets, or gather elm seed pods, or locust tree flowers, to steam with rice, or carefully eke out the wheat flour with corn husks, and cook them up together. ‘Gold-wrapped silver’, that was called, but no amount of fancy names could disguise the fact that they were truly scraping the bottom of the barrel. When Tianyi went to her uncle’s, she tasted preserved eggs, roast duck, steamed shad, all for the first time. Before their little brother Tianke was born, Tianyue and Tianyi used to be dressed in their nicest clothes and taken to see Uncle Huairen and his family often. They were pretty girls back then. His wife, Aunt Hui, was a pretty woman too. Tianyi admired her outfits and hairdo. She was always nicely turned out and, since she had never had children, had a beautiful figure too. She had a Shenyang accent, but a pleasant voice and was very talkative. Given the chance, she would go on for hours criticizing her husband’s army aides. None of those stayed long. Tianyi’s beautiful, clever aunt reckoned they were coarse and inferior, and did not measure up to her exacting standards.

It was obvious that Aunt Hui even looked down on her relatives, especially the female ones, and that included Tianyi’s mother. Actually, Aunt Hui was much younger than her sister-in-law. Only nineteen when she married Tianyi’s uncle, she had been a nurse in a field hospital, her family were comfortably-off market gardeners, and she had completed several years of schooling. Like Tianyi’s mother, she then stopped work and devoted herself to looking after her husband. Years later Tianyi found out how hard it was to be a housewife. Being cooped up at home all day destroyed many women, especially if they had no children to look after.

In Tianyi’s childhood memories, her aunt was always there together with the delicious food smells. Tianyi liked to stand next to her as she cooked, and learned from her how to slice onions on the slant, chop silk gourd into chunks, and how to scrub the chopping board till it was clean of all food stains. She admired her aunt’s pale green flowered, gauzy terylene housecoat, her apron embroidered with doves, her feet, very white in their silver-grey slippers. She loved the décor in her uncle and aunt’s house, where there was not a speck of dust anywhere, and even the tablecloth in the kitchen was fashionably foreign. She knew that her uncle had been to the Soviet Union, India and Morocco. In fact, the kitchen tablecloth with its fine check pattern had probably come from India. As a child, she had adored these things, yet strangely, as the years passed by, she became increasingly puritanical, rejecting all the blandishments that the material world could offer, acting as if she were a monk doing a self-imposed penance. But in her youth, when she was more uncomplicated and before the urge to put on an act took over, she craved everything that came from abroad, collecting whatever she could get her hands on. She knew her mother’s father had once travelled to Germany and Belgium, and her grandmother had a trunk in which she kept a complete German silver service, and toilette boxes, cups and perfume bottles from Belgium. Her grandmother had been dead for many years, but her mother still kept the trunk locked and would not take things out to show anyone.

Once, when her grandmother was in a good mood, she gave Tianyi one of the wooden Belgian toilette boxes, its lid carved in complicated, baroque patterns. Her grandmother had used it for her delicate perfume bottles, covered in engraved silver patterns, and face mirrors with Louis XV ladies painted on the back. The box held a lingering fragrance, even though it was fifty or sixty years old, and the scent should have gone long ago.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Crystal Wedding»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Crystal Wedding» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Crystal Wedding» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.