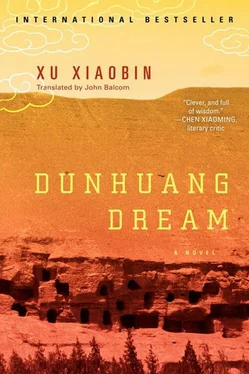

Xu Xiaobin

Dunhuang Dream

Dunhuang Dream , Xu Xiaobin’s novel of romance, intrigue, and crime, is set in the exotic locale of the Mogao Caves in the far west of China. Buddhism, especially in its iconographic aspects and its esoteric Tantric form, pervade the novel and add to the mystery. Given the rich cultural dimensions of the novel, perhaps a very brief introduction is in order.

The main characters of the novel find themselves in the Mogao Caves, popularly known as the Dunhuang Caves, a UN World Heritage Site, which are located in the Hexi Corridor of Gansu Province, China, along what was once part of the fabled Silk Road. Zhang Shu is running away from a bad marriage and decides to travel to Dunhuang, a place he failed to reach as a student during the “Great Link-up,” when revolutionary students traveled around China linking up with their counterparts all over the country during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). Xiao Xingxing, a noted artist, is also fleeing from the boredom of a stifling marriage and seeking inspiration from the art treasures contained in the Dunhuang Caves. Xiang Wuye, a young student of traditional Chinese medicine, is there out of curiosity. A number of secondary characters who live at Dunhuang, such as a collector of folktales, a fortune-teller, a local Tantric master, and corrupt officials, among others, contribute to the depth and richness of the novel.

The Mogao Caves are located southeast of the city of Dunhuang. They were an important religious site for centuries. The first cave was dug out in 366; eventually more than one thousand were dug over the years. From the fourth to the fourteenth centuries, as the caves were excavated, they were also painted; it is estimated that the paintings cover miles of wall. The caves became an important religious site, containing not only the impressive frescoes for which the site is known today, but also a huge repository containing important religious and philosophical manuscripts dating from 406 to 1002 AD. It is estimated that there were approximately fifty thousand manuscripts stored there. The caves were eventually abandoned and only rediscovered in the early 1900s. Today they are an important tourist destination.

Not surprisingly given the backdrop of the story, Buddhism pervades the novel. In fact, the reader will notice that the five chapters are titled with Buddhist terms and concepts: Tathagata, or “thus come one,” a name for the Buddha; Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess of wealth who was absorbed into the Buddhist pantheon; Ganapati, another Hindu god that became a part of the Buddhist pantheon; Guanyin, the Buddhist goddess of mercy; the transformation of the Western Paradise, the Buddhist paradise; and “My mind is Buddha,” an expression stating a fundamental truth of Buddhism that we all possess the Buddha nature.

This structural device is an essential element of the novel. The reader should in no way be intimidated by the detailed descriptions of Buddhist iconography — in point of fact, few Chinese readers of the novel know much about these things. What is important to remember is that the author is juxtaposing an ideal world of religious and philosophical aspirations, which, through its iconic representation, seems to take on a sense of permanence, with the transient, ever-changing world of human affairs and emotions. The lengthy and detailed descriptions of Buddhist deities create verbal frescoes incorporating the historical evolution of the imagery and the symbolic qualities that have accrued over time, creating a sense of timelessness. Thus, against the pervasive, transcendent backdrop of Buddhism, the actions of the characters begin to appear as insignificant and transient as they really are.

Tantric Buddhism is another feature that comes into play in the novel for a number of characters. Tantric Buddhism is also known as Esoteric Buddhism, Vajra Buddhism, and the Secret Sect. While there is a textual tradition to the school, it also places great stress upon ritual, including different forms of yoga. In terms of the artistic representation of such practices, most Western readers will think of Tibetan statues or paintings depicting couples in sexual embrace, one form of yoga practice. The transmission of certain of these teachings is secret and only occurs directly from teacher to student. Supposedly, if the teachings are not practiced properly, they can be quite dangerous or harmful. As pointed out, Tantric Buddhism made its way to China along the Silk Road. In fact, Dunhuang was a repository of Tantric texts, 350 of which are catalogued in the British Library; and, of course, there are a great many tantric paintings to be seen at the Mogao Caves, dating from the Tang dynasty (618–907) to the Yuan dynasty (1279–1367).

By the end of the novel, it becomes evident that perhaps there is a Buddhist moral to the tale. As the Diamond Sutra says: “Everything is like a dream, an illusion, bubbles, shadows, like drops of dew, and a flash of lightning: contemplate them thus.”

J.B.

Monterey

June 2010

1

Tathagata, it is said, refers to the absolute truth as spoken by the Buddha.

Candrakirti, a transmitter of Tibetan Tantric Buddhism, said, “The Tathagata is a five-colored light.”

Tson-kha-pa took it a step further and said, “The absolute truth is the mysterious appreciation of that light.”

For a long time, I mistakenly believed that Tathagata was another name for Shakyamuni. 1When I was young, I would point at an image of Shakyamuni and say, “That’s the Tathagata Buddha.”

It’s not altogether untrue. In Mahayana Buddhism, Shakyamuni is the transformation body of the absolute truth.

Only in Buddhism are two opposing truths enshrined: the basic tenets of Buddhism advocate the practice of discipline, meditation, and wisdom and the avoidance of the three poisons of desire, anger, and ignorance. But Tibetan Tantric Buddhism holds that only when man and woman cultivate the esoteric together — which is to say in a union of the Buddha and the two sexual forces — can a particular state be achieved.

The light of the Tathagata is divided into five colors, most likely in order to suit people’s differing conceptions.

2

Zhang Shu’s wife died. She died in an auto accident.

I heard she was with her lover at the time.

Naturally this put Zhang Shu in an awkward position. But I must say that he didn’t look terribly heartbroken; rather, his expression was more one of resignation. He has aged a lot in the last two years and looks older than most men in their forties. Actually the onset of aging coincides with putting on weight, which is the result of the wasting power of an empty routine and the mediocre. This process is as implacable as the net of Heaven from which no one escapes; it tightens slowly and facilely around a fresh, vibrant life until it expires, ossified amid excessive warmth and comfort.

The ashen pallor preceding ossification had already appeared on Zhang Shu’s face.

“She’s dead and gone. You needn’t take it so hard. You still have the child.” I repeated this obligatory cliché.

He smiled coldly and with his coarse hand stroked his son’s faded hair. “It occurred to me over the last couple of days,” he said, unhappily, “that people don’t have enough ways to express their grief. What is there other than the usual sobbing or tears?”

His words gave one the chills.

“You might have been better off if it had ended three years ago,” I said.

“Who knows? I believe everything is predetermined, ‘Poverty and power have been fixed since the beginning of time; meeting and parting are fated.’” His eyes drifted. “I never left her and the child. On this point I have no regrets.”

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)