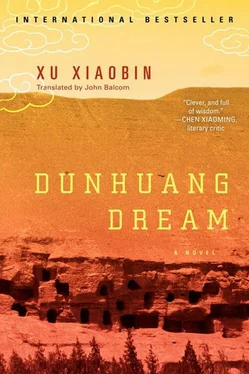

Zhang Shu said that the locals later called the statue the Great Northern Buddha. It was also known as the “White Buddha” and echoed the seated Maitreya, which was twenty-six meters in height, in Cave 130, and referred to as the Great Southern Buddha and also known as the “Black Buddha.” It is said that the Black and White Buddhas are the instigators of all the mysterious disturbances at Dunhuang. That’s what Chen Qing later told him.

15

The calm dignity of the White Buddha stood in sharp contrast to the cold magnificence of the Black Buddha.

The first time Xiao Xingxing saw the Black Buddha, Zhang Shu noticed that she trembled all over. In the dark, he saw her face go white, and on the way back she didn’t speak a word.

The gilt had come off from around the corners of the Black Buddha’s mouth and jaw, exposing the reddish color beneath, which resembled oozing blood.

“It looks like blood, doesn’t it? There is a story!” Old Chen Qing was in high spirits because Xiao Xingxing bought him a bottle of Jiannanchun.

“During the October Revolution, Lenin forced the White Russians into exile, some of whom came to our Thousand Buddhist Caves. One young White Russian lad wanted to scrape some of the gold off the Black Buddha, but couldn’t reach that high, so in his impatience, he fired a gun. Ping! Blood began to flow from the seven apertures in the Black Buddha’s head! Outside, the wind raged and lightning flashed. The Black Buddha reached out and with a flick of his horsetail whisk froze all the Whites Russians to death on the Qilian Mountains. .”

Seeing Xiao Xingxing’s increasing fright, Zhang Shu wanted to prevent Chen Qing from continuing his story.

“There is also a story about the White Buddha,” said Chen Qing, drinking happily. “At the time, carving the White Buddha was a big deal. The red spot on top of the Buddha’s head, which represented the auspicious Buddha’s light, had to be executed in a striking fashion. Later, a monk from the western regions learned of this, so made a long journey to offer a huge ruby, which was placed in the crown of the Buddha’s head. Many, many years later, when the scripture cave was discovered, a lot of westerners showed up and made off with all kinds of precious objects and scriptures. One westerner discovered the red spot on top of the White Buddha’s head. He could see that it was a precious stone. So one night, by the light of the stars, he climbed the nine-storey tower, tied one end of a rope to one of the big beams, and fastened the other end around his waist. He then leaped on top of the Buddha’s head and chipped at the stone with a steel chisel. Flames shot up all around and the ruby cracked. The following day, the monks found a corpse with a rope around its waist in the Main Hall of the Nine-Storey Tower. Later an elderly monk placed a ball of red glass on the crown of the White Buddha’s head. Never again did its dazzling luster appear.”

That day, Zhang Shu and Chen Qing talked late into the night. Xiao Xingxing did not feel well, so she went back to her room to rest. Around midnight, a rainstorm occurred. Amid the wind and rain, the two men could clearly hear the sound of human weeping. Chen Qing sobered up, and Zhang Shu’s hair stood on end.

“Did you hear it, lad? Another disturbance!” Chen Qing staggered out the door, pushing aside the raincoat Zhang Shu offered him. “I shouldn’t talk about the Buddhas. I wonder if the White one is angry or the Black one? Tomorrow I will have to offer incense and add oil to the lamps.”

Muttering, the old man disappeared into the darkness as the sound of weeping drifted more clearly through the rain.

Zhang Shu pulled on his raincoat and took a flashlight to trace the sound of the weeping. He couldn’t believe it, but the sound led him to Xiao Xingxing’s window. Could it be the perpetually happy girl who was crying? Staring at her dark window, all he wanted to do was go in and find out.

16

Xiao Xingxing couldn’t sleep.

For years she had been afraid of the sight of blood, even if it was fake, imaginary, or symbolic.

When her period came each month, she would fall ill.

She had been frightened as a child. Many things frightened her; almost everything frightened her. The illusionary frightened her, but the real even more. At times she would make a scene, but it was in order to suppress her fears. “As a child I was afraid of old women, totally afraid. As a child my eyes always detected something frightening about them. I first experienced this feeling with my maternal grandmother.” So Xiao Xingxing wrote many years later in her autobiography, which she wrote for herself. “My grandmother was a Buddhist and had a large Buddhist shrine standing in her bedroom. It was covered with glass and capped with a red cloth. Inside the glass case was a black Shakyamuni. I often fell asleep under the gaze of that black Buddhist image amid the scent of incense and the rhythmic tapping of the wooden fish. Actually, I went to another world, a black world, which was filled with all sorts of strange and frightening dreams.”

Sometimes, however, her grandmother was quite sweet. For example, her grandmother took her to play at the Puji Temple, which was a holiday for her. On such occasions, her grandmother, who was normally so mean, would become gentle and happy. She would greet everyone with a smile, and others would smile back and call her “Lay Buddhist Rong.” Xingxing never forgot a young woman, also a lay Buddhist, who slipped her a couple of plums, a bright, sensuous red like rubies. She was stupefied. She clutched them in her sleep for several nights and refused to throw them away long after they shriveled up. Another person who fascinated Xingxing was “Lay Buddhist Lin” whose tasty vegetarian food — vegetarian chicken, fish, meat, and gluten — was Xingxing’s favorite as a child, even though it was all made of soy. Then there were those magnificent Buddhist ceremonies when a number of monks in red kasayas knelt on their straw mats intoning the sutras as the incense swirled round the altar and several monks who led the recitation rhythmically beat the wooden fish. Xingxing also had a straw mat on which she sat rather than knelt. In fact, she sat facing the opposite direction, quietly hugging her knees and watching as the group of bald heads rose and fell, like moons, in unison above their red kasayas .

In today’s parlance, Xingxing was a child who suffered from extreme introversion. She practically lived within the confines of her own little world. At night, as her grandmother snored, she would climb the altar and undo the frightful red cloth and speak on her own with the black Shakyamuni. In the shifting light and shadow, she would have the illusion that the Buddhist image would raise its eyes or display a profound smile. Each time this happened, she would feel an indescribable joy, and her heart would throb as if it would leap from her throat.

As a result, she became accustomed from an early age to talking to herself. Often she was assailed by many doubts and unhappiness at night; then, as if by divine revelation, she would know what she had to do after talking with herself.

Her mother and grandmother called her a “little demon” and didn’t much care for her. She knew how to please them, but could never control her facial expressions. She often gave a look that was exactly the opposite of what the situation called for. But even worse, each time she made a face, a voice within her would say: fake. Thus, she’d want to laugh, but later she’d want to cry. After she grew up, her laughter would shine and her crying would be glorious. Most people felt she was broadminded and outspoken. She delighted in this appraisal, but she always feared that people would see through her. In short, hers was a solitude that was incompatible with others.

Читать дальше

![Theresa Cheung - The Dream Dictionary from A to Z [Revised edition] - The Ultimate A–Z to Interpret the Secrets of Your Dreams](/books/692092/theresa-cheung-the-dream-dictionary-from-a-to-z-r-thumb.webp)