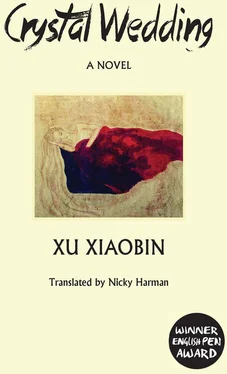

Xiaobin Xu - Crystal Wedding

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Xiaobin Xu - Crystal Wedding» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Balestier Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Crystal Wedding

- Автор:

- Издательство:Balestier Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Crystal Wedding: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Crystal Wedding»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Crystal Wedding — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Crystal Wedding», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Tianyi clutched her baby in arms that would not stop trembling. ‘Let’s go, Lian, let’s go! What are you waiting for?!’ Lian picked up Niuniu’s bag of things and silently followed Tianyi out of the house. Tianke’s furious shouting and swearing followed them all down the road. The Yang family rows made a deep impression on Lian. A dozen years later, when their marriage was truly on the rocks, Lian would stamp in rage and tick off on his fingers all Tianyi’s faults. Among them was her family’s propensity to loud quarrelling.

Two months after this incident, they finally got an apartment of their own, consisting of two bedrooms and a sitting-room in a modern concrete-built block. It was spacious, forty-six or forty-seven square metres. But for some reason, Tianyi did not take the same delight in this as she had with their first home. They had no money to renovate it properly. Tianyi bought the cheapest furniture she could find in the showroom, and still spent more than 700 yuan . It was all made of woodchip, and looked shabby by today’s standards, but it was all they could afford. She got a bed, bedside cabinets, a liquor cabinet, a wardrobe and a bookcase. It was obviously not enough, and Lian managed to pick up some wood from a nearby building site and get some migrant workers to knock together a dressing table, a writing desk and a crockery cupboard, and two more bookcases. The workmanship was shoddy and they charged Tianyi over 300 yuan , which was a week’s food bill. When Tianyi realized just how shoddy, and tried to get them back to fix it, they had vanished without trace.

Tianyi, who held the purse strings in the family, was annoyed. She had been earning her living as a writer for some years now and this money came from her writing, from the sweat of her brow. Money did not grow on trees, and when it was gone it was gone. She asked Lian but he said he did not have a cent in savings, which seemed incredible. But as time went by, she came to believe that Lian really did not have any money. He was a very strange person, one in a hundred, or perhaps one in a million. He was completely scatter-brained in everything he did, acting without planning or forethought. His monthly salary in those days was 300 yuan , and he handed over the lot to Tianyi. But he seemed to need double that, sometimes three or four times. He acted like Tianyi was a bottomless purse. Their relationship was like an accounts ledger: Lent: from Tianyi’s purse. Borrowed: for Lian’s spending. Tianyi came to feel increasingly that Lian was a wild child, grown up in the crack between the rocks, drifting through life completely rudderless. Lian used to say that Tianyi was his rudder. Tianyi was distressed to discover that Lian treated her not only as his wife but also as his mother. It was a terrible thing. The truth was that she herself longed to have a mother who loved her, made a fuss of her. But now Lian had thrust her into a dual role. She had to mother her son and her husband. It was intolerable!

Lian may have had no ready cash but, with an air of mystery, he told her that his family had savings, 50,000 yuan . That was a huge sum in the mid-1980s. But the family had only donated 1,200 yuan for the wedding of their precious only son. Lian had spent every cent of it, and now there was nothing left.

8

T ianyi really had not made enough preparation for her child’s birth, though there was no excuse at her age. In her heart of hearts, she had believed she could reclaim some of her youth by getting married. She did not want a child. She envied the childless yuppies of the west. Let hedonism rule! A late marriage should give her endless pleasure, endless love-making! They would earn big money and buy a car and a house! They would splash out on travel! They would stroll through shopping malls buying fancy clothes! They would have weekends away, go abroad! Emigrate! Whatever form it took, the future promised glittering excitements, but she never even got a taste of the cherry before the child made his grand entrance, and now he was here to stay.

What was even more galling, she loved this child. She felt like she was caught between the devil and the deep blue sea: her baby and the life she wanted to lead. Tianyi had never liked stark, black-and-white choices, but that was what she faced now. Again and again, she had to choose, and it was extremely painful. She had hoped and planned for a different future. Lian never made plans, he just lived from day to day. He never liked thinking very much, and he did not want her to think either.

When it came to looking after her child, Tianyi was intent on avoiding her responsibilities, at least at the start. She felt wounded — by the birth, by her post-natal confinement. She needed a good rest from it all. Whenever she went out, she felt reinvigorated. And she knew that if she was to go out more often, then she needed to do one thing: wean her child off the breast.

Niuniu was two-and-a-half months old. He was such a bonny baby! She used to try and step back, to see him as others did, and her conclusion was always: this little boy was, by any criterion, the bonniest baby she had ever seen. He had beautiful big, limpid eyes, their whites verging on blue, fringed with long eyelashes, enfolded within almond-shaped eyelids; clearly-outlined, cherry lips. His prominent nose and almond eyes were as delicately-crafted as those of a doll. On the day he was one month old, Tianyi took him to the doctor’s to be weighed. When he plumped down on the scales, even the doctor’s mouth dropped open in disbelief. In the first month of his life, this chubby little baby had put on a whole five pounds!

Tianyi cradled him with the utmost care. His sturdy, supple little body was a translucent, alabaster-white all over, with the exception of a purple birthmark on his bottom, the exact same shape as the mark on that Russian leader Gorbachev’s face. Lian joked that their baby had taken the map-like port wine stain off Gorbachev and stuck it on his bum. When he had filled himself with milk, he lay in her arms in the sunshine, and gazed at his mother. One day, his little mouth split open in a smile, such a sweet, glittering smile that Tianyi was almost afraid. It was wholly self-aware, nothing like the instinctive parting of the lips when he had taken his fill. My baby can smile! My baby recognizes me! They said that a baby knows its mother at three months, how come he recognized her at less than two months? He was clearly exceptionally intelligent. Tianyi’s secret delight was no different from that of any ordinary housewife. She suddenly felt she had been drawn into the ranks of foolish mothers and, if she did not take care, she would never get out again!

It was no good! She had to pull back from the brink before it was too late. In her research paper on bisexuality, Tianyi had given her opinion that women were their own worst enemies. And the facts proved it. Look at those swollen-breasted women just delivered of daughters, who had scarcely recovered from the pain of childbirth before they started planning for a son. Were women really born masochists?

Tianyi gritted her teeth and dosed herself with Chinese herbal medicine to dry up her milk supply. Weaning proved to be easy, very easy indeed. But for some unexplained reason, Tianyi suddenly lost a lot of weight after she stopped breast-feeding. She became scrawny, and looked unhealthy. Her chin sharpened, dark rings appeared around her eyes, her nose was oddly red, and her face mottled. She had lost all her good looks. Tianyi felt that if her face got any thinner, she would look like a leprechaun. She just could not bring herself to look in the mirror, could not be bothered to. She put away all the mirrors in the house, and wore sunglasses when she went out of doors. Even so, she was recognized by an old acquaintance at the bus stop, the editor of a women’s magazine. The woman did not mince her words. ‘What on earth have you done to yourself?’ she exclaimed. ‘Most women look fair and plump after they have a child. How come you’ve gone so dark and skinny? I hope you’re not ill! You need to see a doctor.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Crystal Wedding»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Crystal Wedding» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Crystal Wedding» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.