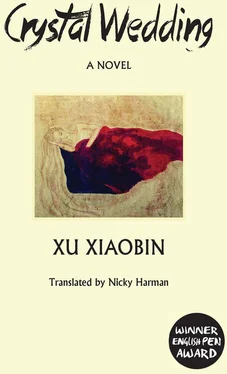

Xiaobin Xu - Crystal Wedding

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Xiaobin Xu - Crystal Wedding» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Balestier Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Crystal Wedding

- Автор:

- Издательство:Balestier Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Crystal Wedding: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Crystal Wedding»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Crystal Wedding — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Crystal Wedding», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

6

Tianyi and Lian had nowhere to live. Their old place was gloomy and had no heating, so was too cold for a baby. They had to move into the room Lian’s parents had rented for them after their wedding, even though it had a shared kitchen and bathroom. Tianyi was astonished at how glum her mother-in-law seemed, apparently unable to raise a smile. Her father-in-law, however, beamed with pleasure at the arrival of the latest little Wang. On her return from hospital, her in-laws looked after them, her father-in-law doing the cooking and her mother-in-law ferrying it to them, while Lian washed the nappies. Tianyi had slept badly in the hospital for a whole week and longed to catch up on some rest. Lian felt so sorry for her that he bundled the baby up and took him to his mother and grandmother to look after for the night. To Tianyi’s surprise, however, no sooner had she shut her eyes than Lian was back with the baby. Tianyi was furious but, when she saw the tears in Lian’s eyes, she swallowed back her anger. It was September, there was a cold wind as Lian carried him across the street, and Niuniu set up a loud wail. Tianyi felt wretched.

‘They said a baby shouldn’t leave its mother.’

‘Not even for a night?’

‘My grandmother said that a baby should be at the breast the whole time.’

Tianyi felt a yawning chasm open up before her, and smiled bitterly. Lian held both her and the baby in his arms, and tears ran down his face. ‘Don’t worry, soon it will be just the three of us and no one to tell us what to do.’ It was the first time that Tianyi saw Lian cry, and the last.

The next day, her in-laws brought dinner over but Tianyi could not get a mouthful down. By now, she had not slept for ten whole days. Her mother-in-law was grim-faced: ‘You two went ahead and had a baby without waiting till you were settled.’ She turned to Tianyi and said brusquely. ‘You got pregnant rather quickly, didn’t you?’ Tianyi was struck dumb. Was this the kind of thing a mother-in-law was supposed to say? She wanted to answer back: ‘Have you lost all humanity? Aren’t you a woman too? Did you never have a child? Aren’t you happy to hold your grandson in your arms?’ She forced herself to swallow the words back and say nothing. She simply could not be bothered. It was all so boring. How had she got herself into this situation? What was going on? Was this the kind of life she was going to have to live from now on? Heaven knows, it was a million miles from the kind of life she really wanted!

‘You got pregnant rather quickly, didn’t you?’ One woman’s criticism of another, the subtle resentment of a young woman by an older one. Tianyi sensed more but could not put a finger on it. She did not discover the real reason for her mother-in-law’s coldness until a couple of years later, by which time the cracks had begun to appear in her marriage.

Everything was different now that, seemingly out of the blue, a third person had arrived in the couple’s world. Niuniu was ravenous, and was taking three bottles of formula milk a day in addition to breast milk. Tianyi had a lot of milk, white, fragrant and rich. The neighbours all commented in astonishment that a woman of her age should have such good milk. Left alone after their visits, Tianyi revelled in the pleasure of motherhood, picking up Niuniu, marvelling at his soft warmth. ‘Look, light,’ she pointed out and his face turned upward. He had a funny little face, his little chin round like a button, no neck, and very large eyes between their enfolding lids. As the days wore on and Tianyi was stuck at home, she soon learnt what the ‘one-month confinement’ meant — pretty much like prison in her view. The only thing that made it better was this little person at her side. She could talk to him, gaze at his sweet little body.

She occupied herself with needlework. She had always done things like that, was better at it than most of her generation. That was thanks to her mother who, when Tianiyi was only six years old, had taught her to knit socks, using those big balls of white cotton yarn. Sometimes, she had used pink, or pale blue. Her mother taught her how to knit a heel and cast off. She was a quick learner, and was soon better at it than her mother. With her unusual aptitude, the socks she knitted looked as if they could have been shop-bought. Then her mother taught her to embroider, to net string-bags, and knit with wool. It took her no time at all to pick up the skills. Her mother had two thick pads of pattern paper, densely covered in embroidered patterns. One of the designs was rather strange: a half-opened flower, at its centre a beautiful girl with very long eyelashes. She practiced the design over and over for a whole evening, using madder pink thread for the petals, light blending to dark and at its deepest at the very centre of the blossom. She made the leaves dark green, and the beauty’s cherry-like lips were scarlet. She was pleased with her results, until her grandmother brought out the teacup coasters she had embroidered when she was young. Flowers embroidered in gold thread on sapphire blue satin, and a pattern of lotus blossoms and roots on a pale green satin background. They were exquisite. On the sapphire blue coasters, the flowers were all edged in gold thread, drawn with an extraordinary sureness of line. The effect was like that of Rococo stained glass. On the pale green piece, silver thread predominated, and the lotus flowers were in a jade white. Both pieces had an embroidered edging, executed in a traditional style with particular skill. The embroidery was so fine on the blooms that there was not the slightest gap to be seen, and it looked like a solid piece of satin.

When she first saw the coasters, Tianyi felt truly moved. They seemed to give her a peek into the lives of women generations before. She thought of her mother and her maternal grandmother, their skin lily-white because it had never seen the sun’s rays, the figure-hugging qipao gowns, with their high necklines, that reposed in their trunks. She suddenly felt a rush of admiration for these old-fashioned women. Perhaps tradition had something going for it after all.

She learned to knit with wool too, and in no time at all was creating all kinds of designs of her own. She progressed to crocheting, tea cosies, and toys crocheted from fibreglass, and then to tailoring. In everything she took up, she was better than any of the girls in their courtyard. Even their neighbour, Aunt Jie, Di and Xian’s mother, was moved to comment: ‘Your Tianyi is so clever, she can learn anything, and she’s so clever with her designs.’

Her needlework certainly came into its own when Niuniu was born. They had no money, so Tianyi bought her own material and made all the baby’s clothes. The results fitted well and looked good too. Di gave her some new woollen yarn and she made Niuniu a little jacket and trousers and hat. The garments were so tiny that, years later, Niuniu took a look at them, and refused to believe that he really had been that small.

One bright sunny day, Tianyi was sitting in the sunshine breast-feeding when her mother-in-law came into the courtyard. ‘How come he’s so pale?’ she exclaimed, ‘You haven’t been putting face powder on him, have you?’ So cold towards her grandson, Tianyi felt, but she choked back a retort and said nothing. Her mother-in-law watched the baby from a distance, but did not appear to want to hold him in her arms. She made a few more idle comments, then turned to go. Tianyi could think of nothing to say. Finally, she took the little boy’s hand and waved it: ‘Say bye-bye to Granny!’ These innocent words triggered her first clash with her mother-in-law.

A couple of weeks later, the older woman returned from a holiday in Guilin and made her husband and her son listen as she recounted the incident. She had not enjoyed her holiday, she said, because all she could think of was Tianyi saying: ‘Say bye-bye to Granny!’ She had understood it to mean that Tianyi did not ever want to see her mother-in-law again, or even that she hoped that she would die down in Guilin and never come home. Her voice was choked with tears and she could hardly get the words out. Lian had to promise to ‘have a word with Tianyi.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Crystal Wedding»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Crystal Wedding» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Crystal Wedding» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.