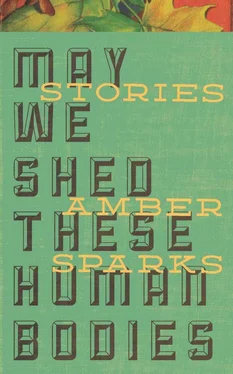

Amber Sparks - May We Shed These Human Bodies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amber Sparks - May We Shed These Human Bodies» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2012, Издательство: Curbside Splendor Publishing Inc., Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:May We Shed These Human Bodies

- Автор:

- Издательство:Curbside Splendor Publishing Inc.

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

May We Shed These Human Bodies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «May We Shed These Human Bodies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

May We Shed These Human Bodies peers through vast spaces and skies with the world's most powerful telescope to find humanity: wild and bright and hard as diamonds.

May We Shed These Human Bodies — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «May We Shed These Human Bodies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

When the Weather Changes You

The year the earth froze hard as diamonds and the sky rained ash, my great-grandparents met and married.

That’s the way the story always starts, with a well-established fact: two people met and were subsequently married. The details surrounding that fact are stranger, less certain. More like smoke than story. More like mirrors than memory.

My sister Anne and I heard the tale a thousand times from our mother. We never heard a word of it from my great-grandmother, an impossibly proud and silent woman. The only time I ever heard her speak was when I was very young and she was very old, and I was summoned briefly to her deathbed.

You have them, she said, her voice surprisingly deep and strong. You have them in your heart, too. Just like me. Her face was purple and mottled, and her mouth collapsed into itself like a rotten fruit.

What, Gramama? I asked, trying not to get too close. The sour smell of death was in the bedclothes. What do I have in my heart?

Ashes, she said. Your heart is full of ashes.

That terrible long winter, the year that all of Yellowstone erupted like one massive volcano, ash and soot filled the sky and mixed with the snow. The entire continent was forced to eat the ash, bathe in it, drink it. Bits of it floated about and stuck in the eye, scratched the skin and clung to the hair.

I wondered if that was what my great-grandmother had meant. If she had drunk of the ashes too deeply and if somehow they clotted and clung in her bloodstream, thickened it, gave it a sluggishness and heaviness — a trait caused by pollution that, like the pepper moths’ coloring, would be passed on via mutation to later generations.

But my sister Anne had another explanation. Loneliness, she said, that’s what she means. We’ve got it in our blood, just like her.

It’s true. My family is a loose confederacy of loners, hooked to others by the double barbs of blood and chance. It’s a mean loneliness, and it sticks in the heart like ash. Nobody stays long. Not in love, not in friendships, not in houses, not even in the same town. We don’t become handsome elderly couples, doubly blessed with long life and lifelong love. The first blessing might be visited upon us, but without the lifelong love it twists back on itself, like the bad fairy’s curse at the christening.

I suppose that would make my great-grandmother the bad fairy. She was an enigma, a widow in her nineties when I knew her. A woman who played Debussy’s Children’s Suite for us and made us giggle, who played Beethoven like a storm while we clutched each other in panic. A woman who was otherwise dour and silent, and who did everything in secret. Even when she smoked it was like she was hiding something, hand cupped around her cigarette the way Nazis smoke in films.

She was severe, disciplined, and she never smiled. Her music was the only passionate, living thing about her. It wrapped her in thick layers, curling and twisting about, and seemed her only channel for expression as she calmly played, back straight as a rod, hair still black and hanging to her waist until the day she died.

Her tale sounds romantic at first, like a love story — but if you listen to the cadences, the code words buried in Edwardian sentiment, you can hear a fire dying out. Cold water quenching flickering embers.

I can never tell it quite right, not like my mother used to tell it. She was a born storyteller. But I tell it anyhow, because it's too important not to pass on.

Listen, my mother would say, and we listened; we leaned forward to absorb the whole story into our skin and blood and bones. Because this is a story about the weather, and what happens when it changes you.

In her youth, my great-grandmother was a beauty and became a minor star on the New York stage. She was light-skinned and black-haired, tall and slender and perfect — except that her lips were thin and wan. This was one of few external signs of the extraordinary silence they held. She spoke so little that you expected her voice to be rusty, to stick like a drawer with disuse; yet it came out deep, dark, coated with lacquer. She looked like Snow White, but her voice belonged to the Wicked Queen.

She had a fairy tale story, too. The little lost orphan left at the train station, the foundling taken in by a family of vaudevillians. That’s where she learned to play the piano, and she grew up there on the stage. But unlike her family, she never took to comedy — or to film, where many of her adopted brothers and sisters ended up.

We saw her in a silent film once, my sister Anne and I. A short little piece called Flowers for A Fallen Angel or something like that. A silly film, full of the borrowed clichés that early silent cinema was partial to. But it was easy to see why her film career never took off. She was meant for the far-away of the stage; from the audience, you couldn’t see my great-grandmother’s eyes. You couldn’t tell that her blood was cold, chalky, or that her eyes were dead and flat. From the audience, you were fooled by the deep, rich voice and the lively black hair. But on film, up close, there was a negative energy around her. Even in photos you see it — like someone sleepwalking and hungry.

My great-grandmother had many admirers, but she was not interested in men or women. She wasn’t interested in sex or even in people; like Garbo, she only wanted to be alone. She was already writing in her veins the DNA of solitude that she would pass on to us. It was as though she had read ahead, could see that after that year she would never be alone again. She was shoring up the fragments of loneliness against her eventual ruin.

It was a bad year that started off like the end of the world. The bang, splash, sizzle of Yellowstone exploding was the trigger. It was like a punishment for Westward Expansion. There was much discussion — but theories, religion, superstition were useless. A whole chunk of Yellowstone had simply gone off and buried itself like Pompeii. And after it went — when the dead were mostly accounted for and the dust settled across the sky like a layer of lead — the new troubles began. Crops and animals and people perished, from starvation, cold, illness, depression, despair. It seemed the whole continent withdrew from the weather and from the living world.

The shut-out sun led to the coldest spring in North America since the Little Ice Age. Gas prices, coal prices, the prices of wood and wool — they skyrocketed that April, as it became apparent that it wasn't getting warmer and the sky was still more black than blue. The poor were dying in record numbers, whole families found frozen, huddled together in dark, iced-over tenements.

After a while, it became common to see strange snow angels here and there. Dead children splayed in dreadful poses, wingless and blue and covered in ice. The crows would circle in frustration, bewildered by the slow rate of decomposition and decay, unable to peck at the eyeballs hard as glass.

It is at this point that my great-grandfather makes his first appearance in the story. It is my great-grandmother's story, really, but he remains the pivot, changed nearly as much as she by that long winter.

He was the only child of the Washington Square Suffrage Society’s leader and often attended Society meetings. If you were a young suffragette living in New York City, you would certainly have heard of him. He would strike you as he struck most observers: a fat man with a slightly stooped back, pretty, almost girlish blue eyes, and an oddly confident air. There was a reason for the confidence, a reason owed entirely to the cold spell.

It had been a good year for my great-grandfather. He had discovered the one thing women wanted more than admiration, more than pretty clothes or fine jewelry, more than food and even love: warmth. And he had discovered he could provide warmth in a very satisfying way for the young women his mother was surrounded by.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «May We Shed These Human Bodies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «May We Shed These Human Bodies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «May We Shed These Human Bodies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.