“Madame,” he said. He stretched out a hand to shake hers.

“Commandant,” she said, accepting it.

“Merci d’être venue.”

He spread a rack of photographs of different men in front of her. She felt a wave of exhaustion buffet her body. This day had been too long. She hesitated, one image swimming before her. Her Turk no longer wore the cheap leather jacket, and his face appeared bruised, or maybe it was just the photo’s lighting. Gone was that gentle expression when he told her about his wife’s homemade yogurt. Still, the photo seemed to be him. She brushed it lightly. The commandant asked her to consider again.

“C’est difficile avec une photo,” she said.

“Il faut être sûr.”

She nodded and thought for a moment. The newscaster had said the suspect had been photo-identified by the witness to the assassination. “Je veux le voir. Le prisonnier. En personne.”

The commandant considered her. He turned and spoke sharply to one of the detectives. “Reveillez-le.”

They would rouse the prisoner. He was in a holding cell within the bowels of the building, awaiting the morning for further interrogation. Which they would want to avoid if they had the wrong man. Again — what a terrible embarrassment this would be for the French police services if the material proof she’d promised proved this to be the case. Even worse if in the meantime they’d mistreated the man they’d picked up. They’d been proud of the speed and efficacy of their forces; this man, the commandant, would have to step forth and admit to their error. His face, like hers, would be all over the newspapers.

She considered the moons on her fingernails, the shine of her engagement diamond, the blank space on the stretch of her hand where the emerald had sparkled and shone such a short while ago. They’d both walked away bearing their own responsibilities — no, she couldn’t go backwards. She couldn’t make what she’d done disappear. That would always be with her. But she could go forward. She no longer blamed Niall for anything.

“S’il vous plaît,” the commandant said.

A part of her hoped against hope that their Turk would be another Turk that looked just like hers. Perhaps the news stations had mixed up her Turk and the police’s Turk’s photos? The man in this photo looked so faded, so crumpled, it was impossible to focus on him. Or maybe it was her exhaustion. She would peek at the real living body and shake her head. She would go home and slide into bed beside Edward and close her eyes against this whole day. She would not sign an affidavit; they would not file her report. No one would be the wiser for it. The British Embassy, the permanent under-secretary would never hear of it.

She shook her head. She and Edward would move to Dublin or not; it made no difference. And whether Niall was alive, whether he would return to the island he loved so much that he was willing to risk all for it, whether he would be forgiven his debt or not and, if he was lucky, meld back into the crowd, another fair-skinned freckled man nearing fifty, scraping by with whatever he could pull together — all of this made no difference to right now. She’d made her decision. And she was sure it was the correct one.

The room spun in front of her. She was so tired.

The second of the detectives returned. She rose and followed him and the commandant along yet another hall and down a set of stairs.

Reaching the bottom, the commandant slowed his step. “C’était courageuse d’être venue,” he said.

The numerous headlines and photographs and, after, the years of Internet traces. Every time anyone Googled her name: her photo, the Turk’s photo, little head shots side by side. Words underneath morphed into whatever shape the public wished to make it. What this might mean for Edward’s career. The boys’ friends, their classmates, their teachers staring at them, whispering as they passed: His mother was the one that stepped forward for that terrorist.

Her, the detective’s, and the commandant’s footsteps slapped rather than echoed through the next hallway. She felt they must be underground, with nothing but earth beneath them, but she’d lost all bearing.

They reached a doorway, and the commandant stopped. “Mais pourquoi vous n’êtes pas venues plus tôt? Pourquoi vous avez attendu pour minuit?” He laid his hand on the doorknob and waited for her to explain. What was she to tell him? That she hadn’t come earlier because she was preoccupied with organizing a dinner party? That she’d waited to bid Niall good-bye, to make sure he could leave Paris without being followed, in case she would now be watched? That she might not have come at all had she not learned that her own son seemed close to repeating her own errors?

“Je suis venue,” she said. That she had come had to be enough.

“Madame Moorhouse,” he said, suddenly in English. “You understand that this is a bad man. Even if he is not the one to do this murder today, this is still a bad man.”

“Because he belongs to a nationalist organization?”

“It has been associated with terrorist acts.”

“Is there any proof that he has?”

“Does that matter?”

“Maybe. Does he still?”

“Still?”

“Belong to this organization? Is he still active in it? And if not, was it involved in terrorist acts when he belonged to it?”

The detective shrugged. “Does this matter either?”

He opened a small window in the door.

She looked at the prisoner lying slumped over a cot. He looked yellower, but his breathing was slightly less heavy.

“He is ill?” she said to the detective. “He is on medication?”

“Yes,” he said, shrugging. “He had une ordonnance in his jacket pocket.”

“C’est lui.”

She withdrew the Turk’s crumpled map from her sweater pocket, with the name of the doctor scrawled on it. She pointed to it

“He was on his way to see this doctor. Here is the name and number,” she said. “It should correspond to the prescription, and if so, you will have a corroborating witness. That will make two witnesses in his defense to one against him. Contact him.” She paused, seeing the commandant’s hesitation. “This is the writing of the man I encountered in the street; you can easily check it against your prisoner’s. I got the map from him. It probably has his DNA on it as well. He was sweating so heavily, he probably sweated right onto the paper. You can check that against your prisoner as well.”

The commandant frowned. He took the paper from her. “Are you sure?” he said, giving her one last chance to turn away from her responsibility.

So little, in the end, was black and white. Perhaps the only thing was humaneness — the innate human response, the thing that made prison guards light a cigarette for a condemned murderer. “Monsieur le Commandant,” she said as he closed the door to the cell, “don’t you see? If you keep the wrong man, no matter what he may have once done, all you achieve is that someone is punished for what he didn’t do and the one who shouldn’t goes free.”

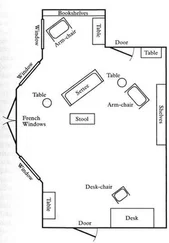

The commandant brought her back to the room in which she had waited. He handed her a pen. She accepted it. He laid an affidavit on the desk. She signed it. He nodded. He led her out to the foyer. A policeman handed her her cell phone, and she cradled it in her hand. It felt strangely warm, and she thought of how just pressing a few buttons would connect her directly to Edward and Jamie. The original detective, the one with so many rings around his tired eyes, reappeared, the lines in his face looking even deeper. The commandant explained Clare’s testimony.

Читать дальше