She followed him out of his office. She stopped to search the street before climbing into the backseat of his car. Was there someone walking towards them? Was there anyone there, a guard, to bear witness to her departure? She was used to climbing into backseats of cars, used to being driven, but this man was a stranger, and no one, not even Edward, knew she was with him. All around them night glistened; the dark lapped at the old stone buildings across the street from them and at the detective’s and her faces. No one at the French Ministry of the Interior would be happy if she discredited the arrest, no one in the French police force. No one at the British Embassy. The news would be on every television station in every city around the world. It would be in every newspaper. The wife of a prominent British diplomat frees a known terrorist and discredits the French police.

But the guy I spoke to on the street is innocent, she thought to herself. He didn’t do it. Not this crime, anyhow. Not if he is the same man they have in custody.

Another detective joined them from within the police station. He mumbled his name, nodded at her rather than offered his hand to shake. She ducked her head and clambered into the car. The front passenger seat was pushed back too far; there wasn’t room for her long legs. She turned them sideways.

The first detective drove. They raced along the Rue de Rivoli, and for the second time in twenty-four hours she felt herself drawn towards the centrifuge of the Place de la Concorde. He turned his car up the Champs Elysées. The two men sat up front while she sat in the back, like a criminal. Their heads from the back looked worn, as though they’d rubbed and rubbed against car headrests. The car smelled of stale cigarettes and fear. There was junk in the backseat: mail, newspapers, empty Vittel water bottles.

She looked at her watch. 2:00 a.m. She was tired, but she had no desire to sleep. On the streets, there were still people walking. She pulled herself to the edge of the car seat and stared out the window. Normal people going home from a night of revelry.

She sat in darkness on the edge of the hotel bed and waited for morning to come to Dublin. With the first light, she stood and went to the window. She tugged on a strand of her hair, pulling it out of the disheveled braid that crossed her shoulder. There was a man weaving his way down the street, a woman sweeping a doorway. The air felt damp, cold, in the hotel room. She drew her arms around herself. She couldn’t imagine that anyone could do what she had just done. She didn’t know how people like Niall, and now her, existed. He’d said bringing the money over would help people, but what had he meant? Help people do what? Was this money really going to help someone buy a First Communion dress for his daughter? Or was it to stain someone else’s dress with blood? She wished Niall had never shown her the contents of that duffel. She wished she had never seen the bills piled up so tightly within it. She wished they were back still combing the sands of the Atlantic while she pretended they were on their honeymoon. And still she wanted Niall with her. Her longing for him was so visceral that she had to sit back down on the bed. She wrapped her arms around herself.

The first time she saw him he was standing on a stone wall. Forever after, she would have the impression he was taller. He was wearing corduroy pants so threadbare she could see the white knobs of his kneecaps through them. He…

Clare’s head knocked against the car window. She sat back and tightened her seat belt as the detective swerved around a double-parked car. They were approaching the Arc de Triomphe. Clare tried to return to her memory, but the image of Niall’s face slipped from her, there but out of reach, like a fish in lake water.

Instead, she saw Jamie’s flushed cheeks, his lips swollen with sleep, her sweater wrapped close around him. She saw his face earlier in the evening as he sat on her bed while she dressed for dinner.

“Madame. Why didn’t you wait to come in the morning?” the detective behind the steering wheel asked her. He was viewing her through the rearview mirror.

In the morning, after the sun had risen, she would be en route to London with Jamie, to speak with the headmaster of Barrow before the weekend was upon them, if the police allowed her to leave Paris. Jamie was within his rights to dissent, but the method had been all wrong, and, just as he’d said, it wasn’t right one person take all the blame. Evasion wasn’t the same thing as absolution. She’d needed twenty-five years of silence and a fifteen-year-old son to make her see this, and she wasn’t going to allow Jamie to make the same mistakes. She would not let this episode become a dark package shoved to the back of his dresser. And she wasn’t going to leave him to return right back to it. If he believed what he had done was justified in some way, he needed to argue his side before facing his punishment. And then he needed to move on.

But she couldn’t leave Paris until she had finished with the police. Not without being sure the man they’d detained was guilty. What if she had not only refused to help Niall but had set herself to stopping him? She couldn’t let another man’s life be wasted because of her cowardice.

She shook her head. “Morning would be too late.”

The detective looked at her again through the rearview mirror. He raised an eyebrow. “Why did you not come earlier?”

She shrugged. She didn’t need to explain to him.

The two men conferred. The one in the passenger seat craned his head around to look at her. He wrinkled his brow and scratched his head. “Vous ne voulez pas téléphoner à quelqu’un à l’Ambassade?”

She shook her head. No, she did not wish to call anyone at the embassy. They’d know all about this soon enough.

The men exchanged glances.

They wove through barren side streets, empty of life or sound, warrens of shadow. They stopped for traffic lights, or didn’t. They pulled up by a stolid fortresslike stone building with none of the glamour or grandeur of the central police station on the Ile de la Cité, though at least as many French flags flew before it. A no-nonsense, double-jointed metal door guarded the entrance. What the gates to Hell would really look like, she thought to herself. No Thinker, no Adam and Eve. No embellishment. She knew of this place. During the German occupation of Paris, it was used by the Gestapo for questioning prisoners. The Ministry of the Interior now had offices on this block.

The second detective slunk out of the car and opened the gate. She and the detective behind the steering wheel drove over cobblestones and through a shadowy archway. He pulled up in front of a group of buildings, got out, and stood there in the night, waiting.

She slid from the backseat.

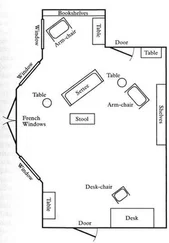

The second detective joined them on the cobblestones. “Par ici,” he said, gesturing towards a door. There was a strange moment while they hesitated in the night, all unsure of the protocol. She was a female, a well-dressed and blond one at that, and a diplomat’s wife. A person of a certain importance. But she was a troublemaker. She stepped forward, leading them, leading herself. Now they followed her. The first detective reached out and opened the door for her. She passed through. They registered her with a clerk, who nodded his head to her but then took her cell phone, led her into an empty room, and asked her to wait. They left her alone with a long solid-wood desk, several folding chairs, not much else. Dustlets floated through the air around her like a clock with no sense of time. She didn’t bother to check her watch again. Eventually the detectives returned, led by a third man, more erect in bearing than the first two but with the air of having recently been awoken.

Читать дальше