A drunk passed by, his body bent in her direction by an invisible wind. She returned to walking. She crossed the bridge, reached the streets of the Ile de la Cité. A young couple, a careless amalgam of loosely draped scarves and shaggy hair, leaned into each other against a tree on the Quai de la Corse. She resisted the urge to stop and stare. She was walking through a coffee-table book of Paris. But she had her final errand of the day to carry out. She kept walking.

A few more moments of moving through the silence and she reached her destination. On her left loomed the monumental Hôtel-Dieu. On her right the massive stone walls of the Préfecture de Police. She’d been here before to process papers. Locals came to the Préfecture to obtain driver’s licenses, and foreigners to become legal. But criminal investigations were also launched within its warren of dim, dusty rooms, as well as projects for municipal public safety. She’d heard as much at a cocktail party. And an office was kept open twenty-four hours to receive criminal complaints.

First she needed to find it. Nothing was ever streamlined in France, least of all bureaucracy. She hesitated in the Préfecture’s shadows, wandering the length of the street until she reached the other bank and Notre-Dame Cathedral. She felt eyes on her, not those of late-night carousers or ambling tourists. Were there guards watching? Normally, she would have sought one out to ask directions, but these guards wouldn’t bob their caps toward her like those she passed every day and had come to know by sight along the Rue de Varenne. She waited until she saw movement around one corner. She followed in its direction. A lone policeman, obscured by the light of night.

“Officer,” she said in the politest French she could muster, “I’m looking for the police station.”

He screwed up his face. “La Préfecture?”

The Préfecture loomed over their shoulders, a huge lacy monument to French bureaucracy. She shook her head. He must think her an idiot.

“No, I mean I wish to speak with someone. About a crime?”

“You have been a victim of crime?”

“No. Not exactly. I want to speak to someone about someone else’s crime.”

“You must go to your central police station if you wish to make a report. In your district.”

“No, but it’s not that kind of a crime. I mean it’s not related to my district.”

He continued to stare patiently at her. “Are you all right, Madame?”

“Yes, yes, I’m fine. It has nothing to do with me.” There wasn’t any point in arguing. Instead, she asked, “Could you tell me please where the closest central police station is?”

After he’d finished explaining, she turned back towards the right bank. The kissing couple was still there; the drunk had moved on. She crossed back over the bridge. A lone taxi waited at the stand by the nightclub. He must have just let someone out. She peered in and saw the driver speaking on his cell phone. She tapped on the window, and he jumped, then scowled with embarrassment. She climbed in.

“Bonsoir, Monsieur. Dix-huit, Rue du Croissant.”

When he drew up by the modern glass-fronted police precinct, the driver betrayed no interest. He put out his hand and accepted her money.

She showed her carte speciale to the policeman at the entry. He lifted the diplomatic identification card between two fingers to examine it, raised an eyebrow.

“Are you here alone, Madame?” he asked in French. And when she nodded, added “Why?”

“Because.”

He looked at her as though to check whether she was insulting him. When he seemed to have decided she wasn’t, he handed her ID card back and pointed to the waiting room. She tried not to look at the others who were waiting also — a young man with an old woman, two middle-aged men — willing herself to become invisible by virtue of not seeing.

Hours seemed to pass rather than minutes. Years, even. The time was late now; the very air felt tired. Finally, the policeman filing complaints motioned to her. To her surprise, when she approached the counter, he smiled.

“Bonjour, Madame.”

“I am here about the murder this afternoon at Versailles,” she said in French. “I have information about the suspect.”

Something almost imperceptible shifted behind the face of the police officer. His smile slackened, and he looked more closely at her. He requested her identification and studied it, glancing back and forth from the photo to her face. “Please take a seat right there,” he responded in French finally, pointing to a nearby chair. “It will be just a few minutes.”

She sat down to wait, his eyes keeping track of her. She felt as though there were eyes in the wall watching her, too, as though she might bolt for a door or evaporate or somehow disintegrate and the building itself wanted to be able to grab hold of her sweater before she might do that. About fifteen minutes later, a plainclothes detective appeared, with as many rings around his eyes as the cross section of a tree.

“Madame Moorhouse?” he said.

“Oui.”

“Suivez-moi, s’il vous plaît.”

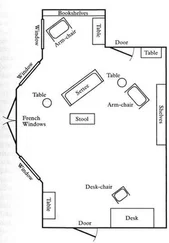

He led her down a long, narrow corridor into a tiny linoleum box of an office.

“You are American,” he said in English after she was seated.

“Yes.”

He fingered the forms she’d filled out and the identity card she’d handed over. “But married to the second at the British Embassy here in Paris.”

“Yes.”

“Does your husband know that you are here?”

She shook away his question as though it were a fly buzzing around her. “Monsieur—”

“There is no one here with you?” He looked around as though someone might have suddenly appeared. Finding no one, he looked back at her.

“The man you arrested — I saw him on the street yesterday. The reason I believe it’s the same man is I saw a photograph of him on a television broadcast. It looked just like him, even the clothing was the same as he was wearing.”

The detective nodded, curious but now impatient. She screwed up her courage.

“But I saw him in the center of Paris, miles away from Versailles, about two minutes before the assassination took place. I spoke with him.”

The detective laid his pen down. “You spoke with him.”

“He gave me a piece of paper that has his handwriting on it.”

“Where?”

“On the paper. It was a map.”

“No, I mean where were you when he gave you this paper?”

“On the Rue Chomel in the septième arrondissement. Outside a flower shop. I had been ordering flowers.”

He sucked the spaces between his teeth. He examined her face, seemed to be considering every last line and angle to it. His jacket was a worn gray herringbone weave; he wore no tie. Finally he asked, “What are you doing out alone at this hour, Madame Moorhouse?”

“Lieutenant, s’il vous plaît. ”

“You understand that there is enormous interest in this case, yes? It is very high profile?”

She nodded.

“You are sure?”

“Yes.”

The detective said nothing, made no motion.

She repeated herself. “Yes.”

He waved a hand in the air. “ Alors. You are ready to identify him? If it is the same man, you will sign an affidavit?”

She nodded.

“Very well.” He picked up the desk phone and began punching in numbers. “This is not the average crime, Madame Moorhouse, you understand. You understand this, Madame Moorhouse?” He addressed his attention to the phone. “Oui, c’est tard.” He continued in a low rumble for a few minutes. After he’d hung up again, he stood.

“Very well,” he said again. “We need to go to the Direction centrale de la police judiciaire at Rue des Saussaies.”

Читать дальше