“Fermez les fenetres dans le salon, s’il vous plaît,” she whispered in his ear.

Cheddar cheese and brie were passed, then cleared away, and the dessert brought out.

“C’est impossible,” the de Louriac fiancée said, probing the plate before her. Even she finished every last bit of cake, strawberry, and chocolate.

And then there was just the coffee to get through and the cognac. Clare watched the orangey liquid swirl in their glasses.

Dinner was over.

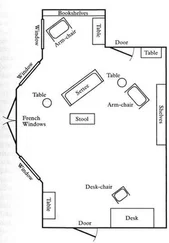

The last of the dinner guests were on their way out, and even with her slip, and although it wasn’t late, their early departure didn’t mean the evening hadn’t been a success. What counted was that the dinner had gone on despite the ambassador’s indisposition, thanks to her and Edward’s last-minute intervention, and his guests had left pleased and relatively satisfied. Certainly the food had been good. Everyone enjoyed a good dinner; they weren’t as common in diplomatic circles as people might think. Insipid roast beef, another stuffed chicken breast in white wine sauce — meals that Mathilde would never permit to exit the doors of her kitchen. Clare patted down a chair in the living room while Edward walked the reverend and his wife to the door. She moved the flowers back from the mantel to the side table. Everyone had been accepting, ultimately, of the ambassador’s sudden indisposition and their equally sudden subsequent intrusion. Clare and Edward hadn’t even been on the original guest list, but hierarchy wasn’t personal in the Foreign Service; the hosts of the dinner that they had had to back out of to hold this one wouldn’t be insulted either. There was something wonderfully pure about the way life within the diplomatic service dispelled any ambiguity as to the link between the personal and professional. People might criticize diplomats for their glibness, but perhaps the transparency of their motives might be considered more honest than the underhanded networking that went on in most professions.

The front door shut, and Edward rejoined her in the quieted living room.

“Well,” he said.

“It went well.”

“Yes. Even with this business about Jamie.”

He sat down in the chair Clare had so recently plumped and folded his hands over his lap. She glanced towards the dining room. “I really should check the kitchen.”

He leaned back and closed his eyes. Still, he tapped his fingers against his thigh. “It’s been a long day.”

“Yes. I’ll just be a moment.” She slid away, passing through the dining room past the now-barren table, the chairs pushed in, the candles and chandeliers darkened, the silver place-card holders back in their spot in the sideboard, all that glimmer and polish retired into silence.

Light streamed from under the closed kitchen door. She swung it open.

Mathilde sat by the central table, dressed in her thick winter coat. Her oversized handbag stood on the wiped-clean table in front of her. She looked up as Clare came in, and grunted. “I’m still waiting.”

When Mathilde worked dinners like this, one of the embassy drivers would take her home after. “No one’s come round yet?” she said. “I’ll call. I’m sorry.”

Mathilde shrugged. “The asperges weren’t bad,” she said, gathering her coat in close to her. “Did the minister like the potato? I went light on the garlic. But can you get someone else in next time? That cousin of Amélie’s is a numpty. C’est un vrai idiot! ”

“What’s a ‘numpty’?“ Clare asked.

“Un vrai idiot.”

Clare shook her head. She was too tired to humor Mathilde. “She’s a nice girl. And she and Amélie work well together.” She looked around for the kitchen phone, but it wasn’t in its cradle. “Let me get my phone.”

She left the kitchen to collect her purse from the console. She couldn’t hear any sound from the formal living room. Who knew how late Edward had had to stay up last night, prepping for today’s meetings? She heard no noise from the rest of the Residence either; perhaps Jamie was also sleeping. She returned to the kitchen. When she opened her purse to retrieve her phone, she caught a glimpse of the Turk’s map.

She snapped her purse shut and pressed the number for the embassy drivers on her phone.

Mathilde eyed her and said, “Thank you, Mrs. Moorhouse.”

“Thank you. I apologize again for making you come in on your day off. Dinner was excellent.”

“I’ll rest here a minute, whilst I wait.”

“Of course. You must be tired. Please don’t worry about lunch tomorrow. And we’re set for tomorrow evening as well. Perhaps you can make a Bundt cake on Saturday.”

Mathilde looked at her good and hard, as though she was memorizing Clare’s face. “Mrs. Moorhouse,” she said.

“Yes?”

“I know there’s ones that say, What can a Scottish woman know about fine cuisine?”

“No one says that, Mathilde.”

Mathilde shrugged this off. “And, I know there’s others that say, What can a Swiss woman know about cooking?”

Clare suppressed the desire to look at her watch. Time seemed to be crawling. The embassy driver had said ten minutes. “Mathilde, you are a wonderful cook. No one argues about that.”

“My father met my mother in a hospital during the war. They started a little hotel together, right after, peaceful-like, in the countryside. I grew up in its kitchen.”

“I’d guessed your childhood must have been something like that.” There was nothing to do but wait. It couldn’t be that much longer. And she’d waited this long — what was another few minutes? “You have such a natural sense for cooking; it’s not something one could learn in a class. Did you just hear the bell?”

“I never took to school,” Mathilde continued, ignoring her question. “I didn’t get on with the other kids. They thought I was suspicious-like, see, because one of my parents was foreign. This was after the war. And I didn’t like sitting there on a wooden chair studying maths and geography from a torn old book either. I was doing my own maths back home, measuring out herbs, figuring out how much flour and how much sugar. And my own science. Making a cake rise — that was what I’d call science. I took first when I did get myself into a cooking course, but I only took the course so I could get a certificate. To get a place somewhere.”

“Yes, I saw that on your résumé,” Clare said. “I’m sure you were ten times better than any of the others.” She wasn’t going to ask how Mathilde had figured out Edward was angling for a new posting, but she could see where this conversation must be headed. Not everyone would put up with Mathilde the way Clare had. But Clare would find someone else in Paris willing to endure Mathilde’s caprices in exchange for the splendor of her culinary skills; the French were at their most tolerant when procuring a good meal was involved. “And when it’s time for the minister and me to leave the Residence, I’ll make sure you’ll be okay. Don’t worry.”

The cook continued to watch her.

“Mrs. Moorhouse?” she finally said.

“Yes?”

“If I might say something just between you and me?”

When had Mathilde ever asked permission to say anything? “Yes, Mathilde?”

“Just remember: What’s for you no go by you.”

Clare had seen this old Scottish saying on a needlepoint pillowcase once, when she’d brought Peter up to school at Fettes. She’d asked the teacher who kept it in his sitting room what it meant. What’s meant for you will not pass you by, he’d told her.

Читать дальше