From his seat at the center of the table, Christian Picq began a discourse in French on the Alsatian village of Hoerdt and why the very best asparagus in the world grew there. His voice was sonorous, probably from giving lectures on sociology year after year in drafty Sorbonne halls; it carried to both ends of the table. “Donc, c’est grâce à la terre très sablonneuse—”

“In Alsace,” Madame de Louriac interjected, also in French, “they would have this as their main course. They wouldn’t serve it as a starter.”

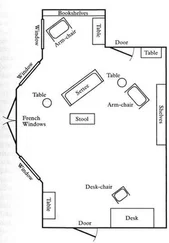

Clare smiled at her guests and sipped from her water glass. Had she made a mistake in serving the asparagus this way? She let an asparagus tip melt into her mouth. It hovered there and evaporated. She looked around. Everyone was eating it. The problem wasn’t the asparagus. Madame de Louriac had expected to be entertained at the ambassador’s residence rather than the minister’s. It had been a shock not just to Clare to discover she’d be entertaining such a lofty gathering in the Residence. It had been a shock to the guests themselves. They felt it. Madame de Louriac wielded her knife in sharp little strokes; she lifted asparagus towards her mouth’s dark oval, creasing the bloodred lipstick she’d used to line it.

“It’s perfect as a starter like this,” Sylvie Picq announced in a clipped tone, and in English. She clinked her fork on the edge of her plate and picked up her glass of white wine. “When they serve les asperges as a main meal in Alsace, they do it completely differently. With thick slabs of jambon blanc and a choice of three sauces. Frankly, it’s old-fashioned to eat it that way. People still do, but it’s an exercise in nostalgia. This is the new way to enjoy it.”

“They are just superb,” the reverend said, wiping his lip with his napkin.

“This is a wonderful time of year,” Dr. Newsome said.

Clare pressed the table-leg button again, and the plates were cleared. The table fell into small pockets of conversation. New wine was poured and the fish was brought out, its lemony sauce streaking the lightly spiced new potatoes. It mingled with the pesto, a springtime pageant of yellow and green. Mathilde had again proved herself a genius. The dinner was going all right. Everything was going all right. She could see Edward down at the other end of the table, nodding at whatever Sylvie Picq, sitting at his right hand, was saying. Clare couldn’t make out the words. She turned to look at the P.U.S. on her own right hand.

“Very impressive, the French police,” the permanent under-secretary was saying. “They caught the culprit in a most expedient manner.”

Here was the waiter again, stepping forward from the shadows to check on their glasses.

“Convicting him is another story,” Lucy Newhouse said, her brown eyes sharp. “He hasn’t confessed, has he?”

The conversation was ricocheting around her. Clare lifted her glass. “Pardon?”

“There’s an eyewitness,” LeTouquet said. “It’s as good as done.”

As good as done?

“Do you mean the assassination? Do you mean the suspect?” she said.

LeTouquet looked at her with surprise. “Haven’t you heard, Mrs. Moorhouse?”

She dropped her hand back on the table. “But how? ” she said. The police were not supposed to find him that quickly, not this evening, not until after Edward’s dinner — not, in fact, at all. The doctor was supposed to have come forward to bear witness, to stop the police from going after him.

But maybe there really hadn’t been any doctor. Maybe that had all been one big story. Maybe the Turk had been sweating from nerves and not because he was ailing.

“Is he all right?” she said.

Eleven heads on swaying necks, peonies on thin stems, shining in the white and gold of the tableware, swiveling to look at her.

“All right?” asked Lucy Newsome gently.

“I mean, did the reports say anything? About his physical condition?”

“The assassin?” asked LeTouquet.

“This isn’t America,” Hope Childs said from the other end of the table, seated as she was down by Edward. “If that’s what you mean. They don’t practice waterboarding and the like in France.”

Childs was a cofounder of an organization called Actors Against Torture. They had gobs of money and a direct conduit to any media outlet they wished, which made them powerful; Edward had explained it to Clare last evening. “What I don’t get,” he’d remarked, “is if they’re against torture, why don’t they set their attentions on some of those films that come out? Not only do they glorify violence in their own right, most of them are torture to sit through.” He’d smiled then, but he wasn’t smiling now. He was staring down the table at her.

“Maybe not, but I doubt the French police will treat a Turk who’s murdered a French official to champagne and a feather pillow,” answered Lucy Newsome, doing her level best to make Clare’s comment seem less startling.

She couldn’t explain what she’d meant, not without betraying what she’d kept hidden. She couldn’t think what to say. She stared back at Edward.

“Our beloved British poet John Donne,” Edward said, cutting into his fish as though she hadn’t said anything, “eventually became a priest in the Church of England, didn’t he, Reverend? Have there been many poet clerics?”

A pause hung over the table, and then, as though in mutual agreement to leave this uncomfortable moment behind them, all heads turned towards Newsome.

“Oh, gobs,” Newsome said. “Here in France, Philip the Chancellor, Hugues Salel; in the U.K., Jonathan Swift, Robert Herrick; in Africa, Desmond Tutu…These are just a few examples. And if you expand the meaning of the word ‘cleric’ to include all religions, you have all the mystics like Sufi or Kabir…Remember, for a long time, members of religious orders were amongst the only people who were literate.”

Clare was saved. Her slip would be forgotten, or at least digested and incorporated into something different. They would probably wonder if she wasn’t criticizing America, which wasn’t good, but it wasn’t quite as bad as suggesting the French would treat their prisoner anything but humanely, especially as there weren’t any Americans present. Or maybe they wouldn’t take it that way either. Even the permanent under-secretary would know she was uncontroversial, apolitical. They would take her strange question as one of those inexplicable Americanisms most likely — a sort of reality-TV response. In what state had they brought him in? Only Edward would know better. She pressed her knee against the table-leg button for the dishes to be cleared.

Conversation picked up again, and wineglasses were raised as the salad course was brought out. Sick or not, doctor or not, the man she’d met on the street wasn’t an assassin. At the very least, he hadn’t been the only person involved, and hadn’t been the one to do the actual killing. She had seen him, she had seen the time. She wasn’t mistaken about that.

“The Musée d’Art Moderne will be opened again soon,” Bautista LeTouquet commented.

“How wonderful,” she said. “Have you had a chance to see it?”

Breeze wafted into the room, and with it the odor of evening. In the gardens of the Rodin Museum, the marble limbs of the statues would be incandescent in the moonlight and cold to the touch, like the memory of a great passion that had faded. The daffodils would cast an eerie glow, the hyacinths be nothing more than dark shadows. The breeze stirred the table, lifting an edge of the tablecloth and setting the flames of the candles dancing. Clare pressed her hidden button again. When the waiter appeared, she beckoned to him to lean in closer.

Читать дальше