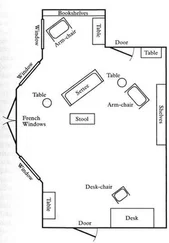

He pulled away from her, straightened. “We have to go in there,” he said, adding, “No sign of rain, for a change,” in a normal, louder voice, and she saw him reassemble his face into its usual calm as he turned back towards the room. He tipped his head in the direction of the reverend, who was chatting with the Picqs. The reverend nodded back and his hand went out; he rested it on Christian Picq’s forearm.

They were discussing the slain official.

She should have canceled the whole damn evening after Jamie’s phone call. Or, at least, after the parliamentarian’s murder. All this desperate effort, putting off Jamie’s problems, trying to ignore her own, just to make this happen.

She watched the group take an almost imperceptible move in towards one another, then move out, like a heart beating. The reverend was speaking.

But, no. She saw the faces on their guests, turning like buttercups towards the light. She and Edward were carrying on not just for the ambassador. They were proving that life would go on, could remain decent no matter what happened, despite the fact that someone could get up in the morning, go to work, and never come home again, because someone disagreed with their opinions, or race, or religion.

She felt flush. Fight Fire with Fire? Setting off explosions by the prime minister’s residence? How could things have gotten to this? How could Jamie be so stupid?

“We need to go in,” Edward repeated.

How? There was a filament loose somewhere inside her, and she’d passed the same disorder on to her Jamie.

“An art student?”

Edward looked at her, his expression clear, unreadable. “Not now,” he said.

He went to join their guests. He left her.

She wanted to go back to Jamie’s bedroom and shake him awake immediately. “What were you thinking!” she wanted to shout. “How could you? Do you think it stops with Chinese party poppers? Do you think it ever stops?”

She wanted to call Barrow and interrupt the headmaster from whatever he might be doing — eating dinner, having cocktails, settling down to a nice book. “Why didn’t anyone there see what was happening to Jamie?” she wanted to say. “What was Barrow doing hiring a girl like that in the first place? At the sports center of all things.” Had she access to the lockers? To the showers? How could they be so stupid as to put young boys together with an unattached girl in that way in such a setting?

Edward had joined the group around the reverend. He was leaning in to listen, looking grave but composed.

“Tout le monde est arrivé?” Yann said, coming up from behind her, holding a tray of empty wineglasses in his hand. “On passe à table?”

“En dix minutes,” she said.

The waiter nodded and returned towards the kitchen.

Chinese firecrackers were a party popper. The Chinese set them off at their New Year: a bit of a bang and then brightly colored streamers shooting out into the sky. Tiny translucent parachutes, like aerial jellyfish floating down against the clouds. Catching the parachutes was considered good luck by the Chinese, and the party poppers were operated even by small children. A toy. That’s how Jamie must have seen it, as though he were playing at superheroes, like he and Peter used to do when they were little, tying towels around their backs as they zoomed up and down the apartment, and the popper would be his magic wand.

A pretty, older Irish girl. The first he’d felt an interest in. Or, perhaps, the first that had shown an interest in him. An antiwar conviction with which he already sympathized, over which he’d even obsessed. Of course he’d agreed to help the girl. Peter wouldn’t have. Edward wouldn’t have. They would have been able to differentiate between what was right and what was wrong — such as stealing from a school lab, such as setting up explosions in central London less than a year after fifty-two civilians had been slaughtered on public transportation — and too sensible to participate during times as troubled as these, no matter how much they liked the girl or agreed with her politics. But not Jamie. Not her Jamie.

“We’ll go for a wee holiday, you and me,” Niall said. He handed her a beer. They were sitting on her aunt and uncle’s patio, and the heat still hadn’t abated. It would turn out to be one of the hottest, driest summers in Boston’s recorded history.

Her heart jumped up. A trip together out in the open, like real couples did?

“To the shore. You’d need to hire the car for me.”

“You don’t have a license?”

“I’m not twenty-five yet. I wouldn’t be old enough as a foreigner. But I found a company that will hire to a twenty-year-old with a license if you are a U.S. citizen.”

She didn’t ask anything more about it. She didn’t even ask where precisely they were going. She followed his directions. She took a one-week leave from her summer job at the museum. She told the landlord of the room she’d rented in Cambridge for the upcoming school year that she’d move in immediately upon her return. She packed a bathing suit, a towel, and a change of clothing. She packed a camera. She did not pack film for it. She put the gold-filled band he gave her into her wallet.

“People pay less mind to a married couple,” he said.

She arrived at the bus station in Boston on the designated day two weeks later. He was there already, lining up to board a vehicle. She shuffled in after him, settled in a separate seat without so much as glancing at him, and got off where he got off in New Jersey, still without saying a word to him. In this second bus terminal, with no one looking, she slipped the false wedding band onto her ring finger. She went to the counter of the car-rental agency without him and filled out the papers for the camper he’d reserved under her name.

“If anyone ever asks where you were,” he’d told her back in Boston while he was explaining how they would travel, “if the car hire comes back to you, you just tell them you were meeting a man and you didn’t want anyone else minding your business. If you put it that way, no one will ask anything more about it, not even your ma and da. They’ll assume it was someone married. And if someone does interrogate you, you just make up a first name, or use the name of someone you know at school, and say he never showed up.”

She hadn’t asked him how or even why anyone would ever find out about her having rented a car in New Jersey. She’d blocked that word “interrogate” right out of her thought processes, though it would come back to her over and over later, like remembering the sound of brakes squealing right before an accident.

She’d just nodded and said okay. She and Niall were going on a trip together. They would be alone, far from the eyes of her aunt and uncle. That was what mattered.

And so, she pulled out of the rental-car lot, mindful to check the side mirrors for incoming traffic — she’d never driven a camper before — and proceeded to the street corner where he’d instructed her he would be waiting. She pulled up to the sidewalk.

“Drive south,” he said, slipping in beside her. Sun beat in through the front windshield; the front seat smelled of chemical solvent. He rolled down his window and flipped down both of the windshield’s sun visors. “Fancy the beach?”

They spent the first night of their trip sleeping in the back of the camper in the parking lot of a public beach, opening up the back doors with slumber still in their eyes and treading down to the lips of the sea at dawn to watch the sun awaken over the Atlantic.

“My green island is on the other side of all that water,” he said.

She whispered, half hoping he wouldn’t hear, “I’d like to go there.”

Читать дальше