“Amélie? You must be joking. She has legs like a piano.”

“She’s not even thirty. Anyway, since when have you been checking her legs out?”

“She spends a fair amount of time up on stools dusting the light fixtures,” he’d said and added, laughing, “It’s hard not to see them.”

“Not nice, Edward.”

“Yes,” he’d said sheepishly. “You’re right. That was uncalled for.” But she’d sensed his abashed relief.

Amélie must be in the kitchen now, helping Mathilde, wondering what had happened in the foyer. Clare needed to go in, restore Amélie’s faith, let Mathilde know she was paying attention. The guests would arrive in hardly an hour. She rose from the bed, turned out the light, closed the door on the room. Like salt, she’d let Jamie slip through her fingers. After she made sure everything was in order, she’d start the calling around. Embarrassing for him, even more embarrassing for her.

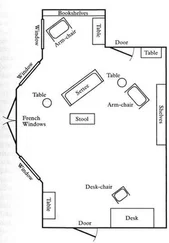

She walked back up the hall. The formal living room looked pristine, its vast space aglow with polished brass and mahogany. Just the sight of it soothed her. This was what she would think about. Her house. Her dinner. This much she could do. A fire had been set, but not lit, in the fireplace. The shiny brass heads of the andirons—“firedogs” Edward called them, using their British name — turned the rest of the room upside down inside their globes; the split logs brought candor to the ensemble. She moved a bouquet from a side table onto the fireplace’s ornate mantel; placing a vase on that table blocked the view from the two chairs beside it to the rest of the room, and people liked to keep an eye on what was going on with other guests, to know with whom everyone else was speaking. She eased a few stems from the vase and reinserted them, causing the bells to face out, pausing to touch their curious domes. Jean-Benoît had done well, as usual. Not only did the combination of the white-and-green bells of Ireland with the yellow lilies convey everything she’d wanted to say about springtime and the bridge between different nations, but they also matched the room.

The flowers perfected, she swept the room with her eyes. Would it pass muster with their illustrious guests of this evening? In their first year at the minister’s residence, with permission and funds from the FCO, she had changed the drapes, the seat covers, the cushions on the settee and matching armchairs from the heavy peach silk favored by the previous inhabitant to a swirl of cool blues and pale browns. She’d bought the fabrics in England and had them sent over, spending hours combing through the samples in Harrods, Osborne & Little, and Chelsea Textiles. For the cushions she’d used woven fabric from Normandy. She had set about sleek pieces of silver from Edward’s family and classic pieces of crystal from her family on the room’s heavy dark furniture, inlaid with golden trim. Under the elaborate chandeliers, and amidst the heavy gilt-framed portraiture belonging to the Residence, she’d hung the large abstract painting by Farouk Hosni they’d bought during their posting in Cairo and the small Sam Gillian they’d purchased while they were first living in Washington. Shortly after the renovations had been completed, she’d straightened up from arranging a vase of simple yellow tulips before a cocktail party to find Jamie standing in the doorway, watching her. “Hey, Mom,” he’d said, his young forehead pleated with puzzlement, “this room matches you now.” She’d laughed, but secretly she’d wondered at his precocious perspicacity.

Yellow tulips symbolized hopeless love. Thank you, Jean-Benoît.

The door to the dining room was open. The table dazzled with fourteen settings of china, crystal, and silver. Amélie had used the pale gray jacquard as instructed, and the royal crest on the plate gleamed against it. Three small bouquets dotted the table. A fourth perched on top of the sideboard. These vases were just right. She didn’t need to readjust them.

She extracted fourteen silver place-card holders from the sideboard and dropped them the length of the table, as though creating a trail. In a short while, her guests would follow them, observing what status they’d been awarded. She did not plan to put up a seating chart outside the door; a seating chart felt too stuffy. For the place cards themselves, she would have to return to the study. She couldn’t hear any sound from the kitchen — usually a good sign. No explosions from Mathilde. After she put out the place cards, there was still her suit to slip into and evening makeup. She’d best check the cheese plate, too, to make sure Mathilde had used the cheddar as directed.

Then she would set herself to locating Jamie.

“Plus doucement!” she heard Mathilde bark as she passed through the kitchen door. The room’s vibrant jumble of odors, industry, and color came as an assault after the regal serenity of the reception rooms. Copper-bottomed pots and smooth gray pans with angular rims, and mounds of green, white, red, and yellow on fat brown cutting boards. A pasty mound of dough covered by a cloth, a second darker mound beside it. A cloud of steam from a pot, a small twister of smoke from the saucepan beside it, the splatter of butter. An aroma of parsley, lemon, and garlic. The scent of chocolate. “Vous les massacrez!”

Amélie was seated at the long central table with her cousin, a twenty-something who wore her frosted hair on top of her head in a vertical ponytail. Stacked rows of asparagus flashed chalky white in two rectangular bowls of water, floating with ice cubes: one with the spears that had already been denuded of their thick exterior and the other for those awaiting disrobement. Clare couldn’t see Mathilde’s face, but she did catch a glimpse of Yann, the waiter sent over from the embassy to stand in for the butler, raising his eyebrows while lining up wineglasses on a tray.

Mathilde cut the air above Amélie’s cousin’s head with a thick red-stained hand. “You’re useless, donnes-moi, I’ll do it!”

“Everything all right?” Clare asked.

Mathilde favored her with a brief glance and practically spit.

“Très bien, Madame Moorhouse,” the waiter responded.

Amélie echoed, “Oui, Madame.” Her cousin made a face into the asparagus and said nothing. Mathilde turned, threw her hands up in the air and retreated to the other end of the table.

“These girls haven’t the faintest idea how to wield a knife,” she said, returning to fashioning rosebuds out of a grasp of strawberries, with a tiny but very sharp-looking paring knife. White and dark chocolate peels curled on a plate beside them. Husked pistachios waited in yet another dish for their turn in the cakes’ assemblage. The cakes would be a masterpiece, like all of Mathilde’s desserts. “They’re making a mess of the asparagus.”

“Et depuis quand ou la Suisse ou l’Ecosse informe le monde gastronome?” muttered Amélie’s cousin, whose grasp of docility did not match her comprehension of the English language.

Since when does either Switzerland or Scotland have the last word on haute cuisine? Clare couldn’t believe her ears. Amélie’s cousin had helped out many a time before. She knew Mathilde’s temper. Was she trying to ruin dinner?

“I heard that!” Mathilde growled, dropping a strawberry. Red liquid dripped from her short, strong fingers and the paring knife. “I heard that!”

“I didn’t hear anything,” Clare said, quickly. She looked around at Yann. “Did you say something?”

“No, Je n’ai rien dit. Ni entendu. ” He pointed to an ear and shook his head. He’d also served at their house tens of times.

“Good heavens, that is going to be incredible,” Clare continued, stepping in between the two ends of the table, blocking Mathilde’s view of Amélie’s cousin at the same time as gesturing towards the fourteen little cakes and the mounds of homemade chocolates and strawberries and pistachios waiting to join them. She suspected there was a freshly blended red-fruit coulis waiting in the refrigerator as well. “You’ve outdone yourself again, Mathilde. Honestly, you make me the envy of every hostess in Paris.”

Читать дальше